ACCLAIM Interviews: Prof. Susan Deacy

Hello everyone, I am Adam Soyler. I am a student at Roehampton University studying History. One of my modules required me to find a work placement. While looking for a placement I came across the Our Mythical Chilldhood project which includes a programme where they use Greek mythology to help and stimulate autistic children. The project offered me a work placement and one of my tasks was to interview members of the project on their experiences. You can find out more about my placement here.

The first interview is with Susan Deacy. It was conducted in March 2021. I hope you enjoy the questions and answers that were produced!!!!

What makes classical mythology the ideal topic to motivate autistic children?

This is an excellent first question, Adam – and it’s one that I have been asking for quite a few years now! It all started in 2008 when, totally unexpectedly, I found out that autistic children often enjoy finding out about classical mythology. I was meeting with a Special Needs teacher at a secondary school in the UK. When the teacher found out that my teaching and research areas include classical myth, she mentioned that in her experience, and the experience of her colleagues, it is classical myth that autistic children are often especially engaged by. Indeed, she said, if there is a subject they really like, it’s often this one! As I left the meeting, I began wondering why this might be the case – and then, over the days that followed, I started to wonder whether there might be something that I myself could DO – something that might help harness this love. And this was why, slowly at first, I began to start investigating the question you yourself began with.

One thing I would stress is that there is huge potential in classical myth to speak to autistic people – including to engage imaginations. It is sometimes assumed that autistic people do not have imaginative lives, possibly because it can be difficult for an autistic person to communicate their experiences and their desires and feelings. But, in fact, autistic people can have rich imaginative lives which can be stimulated by fantasy literature, for example, and films video games, not least games which involve moving though a particular world. And it is here that classical myth can come in – for two main reasons.

Firstly, there are rules! Anyone who is reassured by structures, and who works hard to understand the rules for particular things, can find classical myth appealing. The world of classical myth can look a well-structured one. There are specific kinds of mythological characters, for instance – such as gods, and gods who can be classified in specific ways, for example as “Olympian” and “underworld” or into certain types of role holders. There are gods of the sea for example, and gods of war and gods of skilled craft. While the pantheons of the Greeks and Romans were huge, and could keep being added to, ancient people also liked to think in terms of a fixed number of gods – the major deities who comprised the “Twelve Olympians.” The stories about the gods – from the “Twelve Olympians” to an array of other deities – have been divided into specific categories since ancient times, along with the stories connected with other kinds of beings – heroes, heroines, nymphs for instance and an array of creatures.

Secondly, pretty well anything can go! The rules of the “everyday” world – the world which can be such a source of anxiety for autistic people to negotiate – does not need to apply. The rules – like the ones I set out just now - can be bent, or even set, by each person who engages with the stories. When people from ancient times told stories about mythological characters they could do different – even contradictory – things with them at different times and in different places. Take Hercules for example – I’ve picked Hercules here as an example because Hercules is the main figure I am currently working on for the activities I am developing for autistic children. There could be Hercules the great civiliser for example, or a violent Hercules. There could be the enduring hero, or the cultured hero - a musician for instance or a thoughtful, philosophical figure. Or they could pick a highly masculine Hercules, or a gender-fluid Hercules who takes on the dress, attributes and activities associated generally with women.

To try to sum up – I’ve got carried away, Adam! - what makes classical myth ideal for motivating autistic children is its potential to engage a particular kind of imagination: the imagination of an autistic child. Classical myth can do this because there are so many rules, but also because there is huge – endless even? – scope for each person to go on their own imaginative journey.

How many autistic children do work with at a time/session?

There is no one set number! I’ve visited classes of eight or so children at the Autism Base of a primary school in London. Then, in November of last year, with face-to-face activities difficult or even impossible due to covid, I did something different – I hosted an online session pitched at autistic children and their family members. The great thing about doing things this way – and it’s something I plan to consider even after we can go back into traditional classrooms, cafés etc. – is that many sources of anxiety don’t apply because the activities can be done at home, with family members – so they can be doing something new, something challenging, but without having to travel to and enter some new physical space. Also – for some sessions, any number can potentially work!

How do you deal with the characteristics that autistic children present? Are there any difficulties?

Another great question - although I would stress that if there are difficulties, these are caused by society rather than by the children. One thing I would stress is that being autistic can be associated with various difficulties many of which are caused by dealing with a world that is set up largely by and for non-autistic people. As a result, the world can be a bewildering place, one whose rules might look strange if not bizarre. The activities that I am developing are geared towards helping deal with some of the sources of hardship – even distress – that autistic children can experience. But they are concerned, too, with seeking to enable children to explore their relationships with their surroundings and with their own experiences and perceptions and interests.

Perhaps I could bring in her why it is Hercules that I have picked as the vehicle for these activities? Hercules can serve as an illustration of what it is like to negotiate the world as an autistic person experiencing challenge after challenge, even distress after distress. The life of Hercules is full of with hardships, because there is a deity, Hera, who is devoted to working against him as part of her animosity towards Hercules’s father, her husband Zeus. Then the adult Hercules is set a series of tasks, by Eurystheus, his cousin, a favourite of Hera – each of which ought to be impossible but each of which he succeeds in carrying out. The first involves dealing with a lion from the region of Nemea in Greece – a creature Hera had reared to be the foe of Hercules. This lion, Hercules found out, could not be killed by arrows or a sword – because its skin was invulnerable and so he wrestled the lion instead.

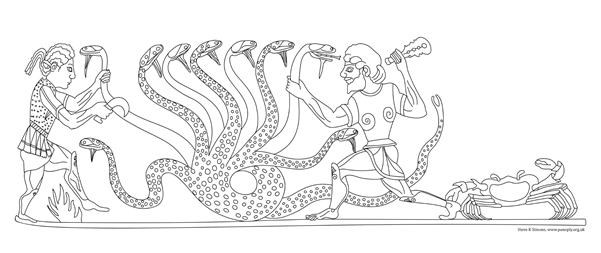

So – Hercules faces a challenge – the need to fight a ferocious lion, and he succeeds because he is able to work out how to deal with the threat it poses. But – and this is why Hercules can speak to an autistic person’s experience – as soon as he succeeds in working out how to deal with the lion and then thereafter how he succeeds in dealing with each successive challenge, he finds himself needing to face some new one. And each time he needs to learn how to deal with each new scenario. For example, after killing the lion, he is set a second task of killing another creature, the Hydra of Lerna, a creature again specially reared by Hera to be his downfall. He works out that the standard way to kill the creature only compounds its threat to him. The Hydra is a many-headed snake. When Hercules cuts off each of her heads, new heads sprout. When he cuts off the new ones, still more appear – and so, helped by his friend Iolaos, as each head is cut off, the severed neck is seared with fire to cauterise the wound.

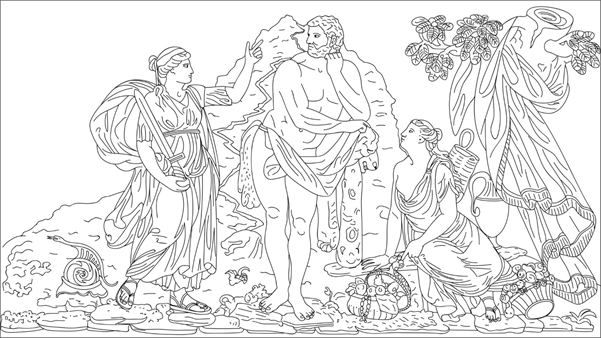

Here’s an example – indeed it is one of the drawings that are used in the lessons. Like all the drawings, this one has been created by the artist Steve Simons.

Hercules is clubbing the creature’s heads, showing his strength but a strength that is wasted on the creature. There is also a creature who has come to the help the Hydra, the crab, who, bites his ankle. Meanwhile, on the ground beneath the scythe-wielding Iolaos is the fire that will cauterise the wounds.

Line drawing by Steve Simons after a late sixth-century (circa 520-510) BCE hydria from Caere in Etruria attributed to the Eagle Painter now in the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles (83.AE.346).

What Hercules goes through can resonate with what it can be like to feel ever perplexed by how the world works with its rules, each time needing to be worked out.

Are there any special techniques you use to keep autistic children stimulated?

In the lessons I’m currently creating – all based around Hercules – the children can start from a pretty straightforward activities and, then, engage increasingly deeply with the topic. The lessons start with the children being shown a specific object or objects relevant to the lesson, such as one or two of Steve’s drawings. They then “Talk About” a particular aspect of the experiences of Hercules and/or those he encounters. A “Creative Activity” comes next, followed by the final “Do Something More Complex” section which includes activities such as discussing emotions, discussing decision making and discussing causality. Throughout – and in keeping with the mythological episodes the lessons deal with – I have sought a blend of “hard work” and “fun.”

When you presented to the autistic children the two contrasting life choices virtue and pleasure how did the autistic children react to these two ways of life?

This question follows on beautifully from the one I have just finished answering, Adam! The activities concern lots of aspects of the life of Hercules in classical myth – but in particular they focus on a particular episode. The episode concerns the time when, sometimes when he is on the cusp of adulthood, Hercules enters a curious place where he meets two women, or goddesses, each of whom offers a particular path in life –one a life of Hard Work, the other a life of Pleasure.

I picked this episode initially because the thing that Hercules is tasked with in the episode – making a choice – is relevant to just how difficult it can be for autistic people to make choices - whether about “big things” or “small things.” The more I looked at the image in relation to autism, the more I could see its potential as a focus for the various activities. I am currently finishing off a book which presents ten sessions based around this story. I could do more too, as I set out. It is a very rich story…

There is a particular “Roehampton” dimension as well which I should mention, not least because we are both of us members of the Roehampton community! The activities are based around an eighteenth-century representation of the Choice, in the Adam Room in Grove House on the Froebel campus. Here is the photograph was taken a few years ago by another Roehampton colleague, Marina Vorobieva, who is also a photographer.

Choice of Hercules chimneypiece panel, from the Carter Workshop, late eighteenth century, in the Adam Room, Grove House at the University of Roehampton. Photograph by Marina Vorobieva.

The objects depicted on the side of Pleasure include bowls of fruit and a drinking vessel. The features of the other side include boulders, a mountain with a steep craggy path, a sword, and a helmet fringed by a serpent, or over which a serpent crawls, suggesting the rocky landscape, though also, perhaps, the travails of a hero set to face serpentine opponents and, ultimately, immortalization. Hercules is caught in the process of trying to decide, his face turned towards Hard Work, his body towards Pleasure.

And here are some of the drawings that Steve has created of the panel for the lessons.

Choice of Hercules chimney piece panel along with some of the details, redrawn by Steven Simons

Steve is an animator! He has also created an animation of Hercules choosing – also for the lessons!

The lessons offer an opportunity to think about impact of what Hercules chooses on his subsequent adventures. If he chooses Pleasure – what might this mean? If he chooses Hard Work, what would this mean for his future? The children will be invited to choose between, on the one hand, the helmet, serpent, sword and woman pointing up the hillside, and, on the other hand, the fruit, flowers and the drinking vessel and the woman seated in the midst of these features. As there is no “right” choice or “wrong” choice, the episode provides an opportunity for reflecting on how and what to choose and crucially on what the implications might be and on the various ways in which a course of action can impact on the future.

Therefore the episode help autistic people assess the consequences of an action. I’m struck that the episode can indeed be a source of “Social Stories” which, since their development in the early 1990s by Carol Gray, have been key in autistic pedagogy.

What makes Hercules so special in bringing out confidence in autistic children?

Hercules can be an epitome of what can happen when an autistic person finds the civilised world so overwhelming that they experience the “volcano effect.” An autistic person’s experience of the world might be an intense one, due to heightened sensory experiences and finding it hard – or impossible – to filter out background noise. Being autistic can be like experiencing a recurrent panic attack, including coming out of needing to process lots of information in one go. It can be hard, too, to regulate emotions. An autistic person might not show the “appropriate” emotion, despite what they might be feeling. Indeed, it could be that they are feeling lots of things, and this could lead to an intense response, or a shutdown. The default emotion is often anxiety – and this can mask other emotions, like joy, or happiness. To be an autistic child can be to experience bewilderments, sensory overload, isolation, and frustration which can, in some cases, lead to moments of violence against oneself or against someone else.

But the world of an autistic person can be an exciting one. And Hercules as the great adventurer, and as the great lover of life – who loves eating and drinking for instance, and making music – Hercules can speak not just to difficulties faced by autistic children, but also by the things in life that they love.

When I have shared the above aspects of Hercules with autistic people, I have been consulting with the response has been “that sounds like being autistic.”

When you went to Warsaw and presented presentations on Hercules how did you find it?

Amazing! Particularly due to the support and interest of colleagues from around the world, from school students and from the autistic people who have taken part in workshops I have run in a café called Life is Cool, which is staffed by autistic people. The support of coordinator of the events I’ve run, the inspirational Professor Katarzyna Marciniak, has made me feel nothing short of welcome in Warsaw!

Were there any regrets or anything you wished you could have done differently while experiencing Poland?

The only regret is that that the pandemic has prevented me from making the further visits to Warsaw that I had been planning.

Are there any difficulties communicating to the people who do research in Warsaw?

The opposite! It’s at Warsaw that, if anywhere, I have communicated my research especially clearly – helped by the support and interest of the colleagues there. The sessions in the autistic café were helped too by the presence of translators, who each time were fluent in both Polish and English and who had experience working with autistic people.

Has Covid affected your programme or research at all and if it has how it affected it?

Yes and no! My plans for visits to classrooms and for further visits to the Life is Cool café in Warsaw have been put on hold. But instead I have discovered the potential for using platforms like Zoom which can have their own, distinctive energy. Like I said earlier, I would like to run more of these – even after the pandemic is over.

Thank you very much, Susan!

Thank you too, Adam; it has been a pleasure!