Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

René Goscinny, Albert Uderzo, "Les Lauriers de César", Pilote 621, 1972.

ISBN

Genre

Comics (Graphic works)

Target Audience

Crossover (Children and Young Adults)

Cover

We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover.

Author of the Entry:

Lisa Dunbar Solas, OMC contributor, drlisasolas@ancientexplorer.com.au

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

René Goscinny

, 1926 - 1977

(Author)

René Goscinny was born in 1926 in Paris. He was the son of Jewish immigrants to France from Poland. Born in Paris, he moved with his family to Buenos Aires, Argentina, at the age of two. In 1943 he was forced into work by his father’s death, eventually gaining work as an illustrator in an advertising firm. Living in New York by 1945, Goscinny was approaching the usual age of compulsory military service. However, rather than join the United States Army, he elected to return to his native France to complete its year-long period of service. Throughout 1946, Goscinny was with the 141st Alpine Infantry Battalion, and found an artistic outlet in the unit’s official and semi-official posters and comics. His first commissioned illustrated work followed in 1947, but he then entered into a period of hardship upon moving back to New York City. Some important networking occurred thereafter with other emerging comic artists, before Goscinny returned to France in 1951 to work at the World Press Agency. There, he met lifelong collaborator, Albert Uderzo, with whom he co-founded the Édipresse/Édifrance syndicate and began publishing original material.

As Edipresse/Edifrance developed, Goscinny continued to work across a number of publications in the 1950s, including Tintin magazine from 1956. A key output from this period was a collaboration with Maurice De Bevere (1923–2001). They created together series of comics: about Lucky Luke (with Maurice), and about Asterix (with Uderzo). Goscinny worked with Jean Jacques Sempe and they created a series about boy called Nicolas.

The following year (1959), the syndicate launched its own magazine, Pilote; and the first issue contained the earliest adventure of ‘Astérix, the Gaul’, scripted by Goscinny himself, and drawn by Uderzo. On the back of Astérix, Pilote was a huge success, but managing a magazine was a challenge for the members of the syndicate. Georges Dargaud (1911–1990) – publisher of Tintin, and a major force in Franco-Belgian comics – saw the opportunity to purchase Pilote in 1960, and put it on a firmer footing, financially. Already the leading script-writer on the magazine, Goscinny was co-editor-in-chief of Pilote from 1960. Such was its success that by 1962, he was able to leave Tintin magazine in to edit Pilote full-time, and he held that role until 1973.

Goscinny’s success with Astérix and Lucky Luke (published in serialized instalments in the magazine, as well as in album-form by Dargaud) saw him enjoy a comfortable life, but this arguably contributed to his growing ill-health. He had married in 1967 – to Gilberte Pollaro-Millo – and a daughter – Anne Goscinny – was born the following year, as he continued to work with Uderzo and others. Pilote and Astérix were sufficiently profitable to be a full-time job, and twenty-three Astérix adventures were completed by 1977, when Goscinny died suddenly of a cardiac arrest during a routine stress test. Uderzo completed the story Astérix chez les Belges [Asterix in Belgium] and continued the series alone.

Goscinny was not only a comic book author but also a director and co–director of animated movies (Daisy Town, Asterix and Cleopatra), feature movies (Les Gaspards, Le Viager). Goscinny. He died in 1977 in Paris.

Sources:

bookreports.info (accessed: September 14, 2018)

britannica.com (accessed: September 14, 2018)

lambiek.net (accessed: September 14, 2018)

Bio prepared by Agnieszka Maciejewska, University of Warsaw, agnieszka.maciejewska@student.uw.edu.pl and Richard Scully, University of New England, Armidale rscully@une.edu.au

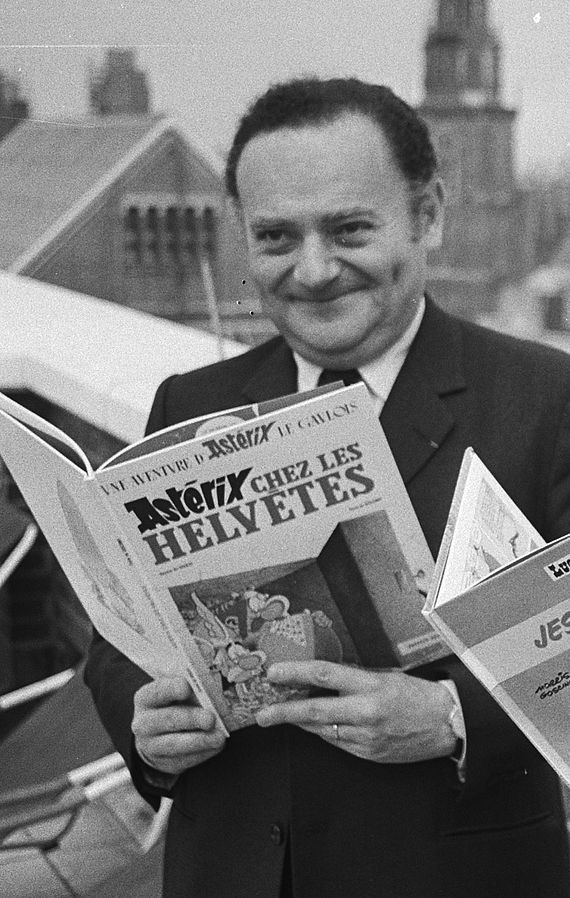

Albert Uderzo in 1973 by Gilles Desjardins. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 (accessed: December 30, 2021).

Albert Uderzo

, 1927 - 2020

(Illustrator)

Albert Uderzo was born in Fismes, France, in 1927. The son of Italian immigrants, he experienced discrimination following the family’s move to Paris, at a time when Fascist Italy was pursuing an aggressive course, internationally (on top of the usual xenophobia directed at immigrants). Uderzo came into contact with American-imported comics around the late 1930s (including Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck). He also discovered that he was colour-blind (despite art being the only successful aspect of his schooling career). Living in German-occupied France, from 1940, Uderzo tried his hand at aircraft engineering, but illustration was where he found his métier. Post-war, he came into contact with the circles of Belgian-French comics artists; as well as meeting and marrying Ada Milani in 1953 (who gave birth to a daughter, Sylvie Uderzo in 1953).

He started his career as an illustrator after World War II. In 1951, he met René Goscinny at the World Press Agency. Together, they worked on a comic: ‘Oumpah-pah le Peau-Rouge’ [Ompa-pa the Redskin] – drawn by Uderzo and written by Goscinny. In 1959 Uderzo and Goscinny were editors of Pilote magazine. They published there their first Asterix episode which became one of the most famous comic stories in history. Individual albums of Astérix adventures appeared regularly from 1961 (published by Georges Dargaud following the completion of the serialized run in Pilote), and there were 23 completed adventures by the time Goscinny died in mid-1977. After Goscinny’s death, Uderzo took over the writing and continued publishing Asterix adventures, and completed 11 further albums by retirement in 2011 (including several that were compendiums of older material, co-created by Goscinny). In the late 2000s and early 2010s, Uderzo experienced considerable family disquiet; largely over the financial benefits expected to accrue to his daughter. Although maintaining for much of his career that Astérix would end with his death, he agreed to sell his interest in the character to Hachette Livre, who has continued the series since 2011, owing to the talents of Jean-Yves Ferri and Didier Conrad.

All stories about Asterix published till now are very successful and widely known. They are highly popular not only in France but have been translated into one hundred and ten languages and dialects. The series continues and Asterix (Le papyrus de Cesar) became the number one bestseller in France in 2015 with 1,619,000 copies sold. The sales figures and popularity of Asterix series are comparable with the Harry Potter phenomenon. Astérix et la Transitalique published in “2017 placed 76 among the French Amazon best sellers three weeks before it was published Among comic books for adolescents the title was number one, among comic books of all categories it was number two.”*

Albert Uderzo died on 24 March 2020.

Sources:

lambiek.net (accessed September 14, 2018).

Bio prepared by Agnieszka Maciejewska, University of Warsaw, agnieszka.maciejewska@student.uw.edu.pl and Richard Scully, University of New England, Armidale rscully@une.edu.au

*See Elżbieta Olechowska, “New Mythological Hybrids Are Born in Bande Dessinée: Greek Myths as Seen by Joann Sfar and Christophe Blain” in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Chasing Mythical Beasts…The Reception of Creatures from Graeco-Roman Mythology in Children’s & Young Adults’ Culture as a Transformation Marker, forthcoming.

Translation

The Laurel Wreath has been translated into at least 20 languages.

Summary

Asterix and the Laurel Wreath is the 18th story in the Astérix comic series (see also entries for Book 4, Book 6, Book 12, Book 17).

The story commences with Astérix and Obélix in Ancient Rome pondering whether they have made a mistake travelling to the city. An explanatory flashback takes the story Lutetia, the Roman name for modern day Paris. At Lutetia, Astérix and Obélix travel as part of a dinner party that includes Chief Abraracourcix (à bras raccourcis, Vitalstatistix in English) and his wife, Bonemine (bonne mine, Impedimenta in English) to the home of Homéopatix, Bonemine’s brother and a rich businessman. During the lavish dinner, Homéopatix offends his brother-in-law by claiming his meal is far superior to what he serves back home. The intoxicated Abraracourcix then declares that he can obtain something that money simply cannot buy: he can have made a seasoned stew with Julius Caesar’s laurel wreath! Then, a drunk Obélix volunteers to obtain the laurel wreath with Astérix’s help.

Returning to the present, Astérix and Obélix stand in front of Caesar’s palace in Rome, brainstorming and hatching a plan to get into the palace and steal the wreath. Fortunately, they meet a kitchen slave in a tavern, who explains that Caesar usually obtains his slaves from Tifus (Typhus), a slave trader. Inspired by this conversation, Astérix comes up with a clever plan to get into the palace; he and Obélix will present themselves to Tifus as slaves. They find Tifus and he agrees to the sell them. The trader presents the Gauls at the market, along with other slaves. Just as the other slaves begin a fight with Astérix and Obélix, Claudius Quiquilfus (Osseus Humerus in English), a wealthy patrician, comes by. He is amused by the Gauls and offers to buy them. Astérix mistakes him for Caesar and they are sold. Once they are transported to his household and are placed under the supervision of the chief slave, Garedefréjus (gare de Fréjus, Goldendelicius in English). Garedefréjus immediately takes a disliking to the pair because they were sold by Tifus, and by association, are more elevated in status and a threat to his leadership.

Shortly after their arrival, the Gauls realise their mistake and hatch a plan to get Quiquilfus to return them to Typhus. They begin by cooking a vile stew, which by accident acts as a miraculous hangover cure. When this fails to have the desired impact, they then make noise at night, disturbing the sleep of Quiquilfus’ family. Once again, this scheme fails, with the family deciding to throw an impromptu party. The following day, an exhausted Quiquilfus sends the Gauls to Caesar’s palace to explain his absence to the secretary. While they are gone, Garedefréjus tells the palace’s guards that the Gauls are planning to kill Caesar. The guards seize Astérix and Obélix once they arrive at the palace and imprison them on the charge of attempted murder. That night, they escape and search for the wreath, but at dawn, they are forced to return to their cell unsuccessful. They then adjust their plan; they intend to search for Caesar and take the wreath from him.

Meanwhile, a lawyer arrives at the palace to defend the pair in a public trial, although he assumes that the pair are guilty and will be fed to the lions in the Circus Maximus. Curiously, Astérix enquires whether Caesar will attend this execution, and the lawyer indicates that it is possible. The trial begins but the proceedings are suspended when the prosecutor makes the speech the defence lawyer intended to give. Wishing to be sentenced, Astérix defends himself and confesses to all the "wrongdoings" he and Obélix committed. He also makes a plea for the wild animals that will go hungry if they are not found guilty. A moved judge sentences the pair to death. For their last meal, Tifus and Quiquilfus host a feast of extravagant dishes for them.

Astérix and Obélix are presented at the Circus but soon after, they discover that Caesar is not present; he has left Rome to pursue pirates. The Gauls refuse to enter the arena and this leads to chaos. The starving felines begin to attack one another and the audience starts a mass riot. All spectators and the Gauls are then thrown out of the arena.

Free but without shelter, the Gauls sleep in a doorway on the streets but are awoken by noisy brigands. They get into a fight and defeat them. Habeascorpus, the chief, then offers them shelter in return for their help to execute robberies. Astérix agrees, but when they are ordered to rob their first victim, they discover it is a highly intoxicated Gracchus Quiquilfus (Metatarsus in English). The Gauls refuse to attack him and turn against the brigands. Once defeated, they learn from Gracchus Quiquilfus that Garedefréjus has been elevated to Caesar’s personal slave and that Caesar, who recently won his battle with the pirates, is expected to hold a Triumph, an elaborate public and religious ceremony in celebration of his success.

The Gauls find Garedefréjus in a tavern and persuade him to exchange Caesar’s wreath for one made of fenouil (parsley in English). During the ceremony the following day, Garedefréjus anxiously holds the fake wreath over Caesar’s head. The proconsul does not seem to notice, but ponders why he "feels like a piece of fish"*.

The successful Gauls return to Lutetia and present the wreath to Chief Abraracourcix. Then, Homéopatix arrives at the chief’s village and is presented with the laurel wreath stew. Abraracourcix declares with pride that no one could prepare such a meal. Homéopatix agrees, but mocks him, announcing that it is an overcooked dish. Enraged, Abraracourcix hits him.

The story ends with a postscript informing the reader that Astérix’s vile stew was widely available and used by the Romans and has, therefore, caused them to party excessively and this caused the decline of the empire.

* R. Goscinny and A. Uderzo, “Asterix and the Laurel Wreath” in Asterix Omnibus 6, London: Orion Children’s, 2012, 107–152, 151.

Analysis

Asterix and the Laurel Wreath is a humorous story set during the Gallic wars. The wars were a series of Roman military campaigns against Gaulish tribes led by Julius Caesar, a proconsul. The comic draws on major cultural symbols, themes and issues related to the Roman and Gaul interaction and through subversive humor and clever wordplay, engages the reader in a discourse about modern life, with particular emphasis on topics such as power dynamics, friendships, inequality and slavery. The brilliant puns, in particular, reflect the outstanding translation of Andrea Bell.

Slavery is a central theme of the story, through which the authors explore the nature of power relationships and struggles as well as socio-economic inequality. The main characters represent the major ranks within Roman slavery. Caesar and Claudius Quiquilfus (Osseus Humerus) represent the Roman elite and retainers, the top tier of the hierarchy. Romans retained slaves as a symbol of status and ordered them to perform tasks and services that were dangerous, difficult or considered to be beneath their owner*. Meanwhile, Tifus (Typhus) represents the slave trader, the intermediary between slaves and the retainers. The heterogeneous group of Roman slaves are represented by the Gauls, Garedefréjus (Goldendelicius) and other individuals sold at the market, reflecting accurately that slaves generally fell into two main types in Greek and Roman society: native slaves (oikogeneis, vernae); and, those who were brought from outside their homeland.** As the story outlines, slavery also had an internal hierarchy. Selected slaves were also given supervisory roles, such as overseeing city accounts, and they were assigned these responsibilities because they were "an outsider" and therefore, could not partake in matters central to the lives of citizens.*** In the narrative, Goldendelicius is given supervisory roles in the households of Quiquilfus (Humerus) and Caesar.

In the story, food, friendship and feasting are fundamental in the development and subversion of power relationships. In both the Roman and Gaul contexts, food acts like currency, representing wealth and power. Alcohol is an exception: its consumption is portrayed as an agent of conflict and dissolution. A number of the characters of the story are named after food, including apples and tapioca, and this possibly reflects stereotypes of Italian food culture. Relationships are strengthened and disputes arise during the preparation and consumption of food and drink. From a historical perspective, feasting was an important social practice in the Roman world.**** The banquet was known generally as the convivium, meaning "living together".***** In the comic, two types of convivium are portrayed: the cena, a meal held mid-afternoon and in the evening at a private residence; and, the commissatio, the drinking party. Romans also introduced feasting to the Gaulish landscape****** and this transferral is alluded to when Homéopatix (Homeopathix) hosts a dinner at his home and it is referred to as a "cena" (Goscinny and Uderzo 2012, p. 113)******* Throughout the narrative, drunkenness and disorderly behaviour of principal male characters leads to disputes, violence, and even the eventual demise of the Roman Empire. Through these events, readers are afforded opportunity to reflect on the effects of excessive alcohol consumption on social relationships, and also how the authors portray traditional constructions of masculinity. Asterix and Obelix's playful and childlike nature subverts the Roman display of extravagance and wealth through feasting. The mischievous pair wreaks havoc in Humerus’ kitchen while preparing food for the cena. As part of their plot to be returned to Tifus (Typhus), they playfully throw together a soup as if they were children making magical potions or "paddy cakes" in the kitchen. While their creation emits a terrible smell, the soup ironically becomes a hangover cure and much later, the indirect cause of the demise of the Roman Empire.

The dynamics of power within the slavery system are explored particularly through the relationships between Garedefréjus (Goldendelicius), his Roman owners and the Gauls. The naming of the main characters helps to symbolically convey the author’s fundamental ideas about slavery. In building the Roman social structure, the translator named several Roman characters after parts of the human skeletal system; for example, Claudius Quiquilfus (qui qu'ils fussent) is translated as Osseus Humerus, which is the bone that extends from the shoulder to the elbow. His son Gracchus is named after the metatarsus, the five bones in the foot located between ankle and toes. The reference to human anatomy builds the idea that Roman society is well-connected and has a central framework. Meanwhile, Tifus (Typhus)’ name is derived from a nasty infectious disease transmitted to humans from fleas that have been in contact with rodents and other inflected animals. Typhus as the slave trader represents the "vector" through which slavery, a social plaque, is spread through society. As an interrelated historical note, slavery was also a means through which infectious diseases were transmitted globally (see Alden and Miller 1987, for instance)********.

Critically, Garedefréjus (Goldendelicius) is portrayed as a tricky slave but also a victim of the system. He possesses traits of a Plautian "clever slave": he devises devious schemes and drives the plot. These aspects of his character are particularly evident in his interactions with Asterix and Obelix. He becomes jealous and concerned about his position when the Gauls demonstrate their apt abilities and begin to win the favour of Quiquilfus and his family. Notably, his English name is derived from the golden delicious apple (Malus domestica), which is a sweet and popular variety first cultivated in the United States in the early twentieth century. Notably, Garedefréjus (Goldendelicius) uses trickery and deception to yield power and elevate his position. He demonstrates this when he lies to Caesar’s guards and on his word, they then arrest the Gauls on the charge of attempting to murder Caesar. Garedefréjus benefits from the situation by becoming Caesar’s lead slave. Here, the authors seem to suggest that rising through the ranks of slavery is best facilitated through deception, and not by merit. While Garedefréjus is conniving, he sadly remains a victim. He does not use his skills to break free from the system. Meanwhile, he views himself through a dehumanised lens; he is nothing more than as a commodity. This is most clear when he agrees to replace the wreath and hand it over to the Gauls. He tells them happily that he has been assigned the role of holding it during the procession and states, "For a slave it’s the crowning glory! Now, I’m a collector’s item too!" (Goscinny and Uderzo 2012, p. 150). Through the portrayal of Garedefréjus, authors highlight the acute damage slavery inflicts on the human psyche.

The story cleverly undermines Roman power through the subversion of the laurel wreath, a central symbol of their power and authority. In the classical world, the laurel wreath was a multi-vocal symbol associated with "achievement" and victory. Often round or a U-shape, the wreath was made from bay laurel (Laurus nobilis), an aromatic plant that grows in the Mediterranean. When worn as a chaplet, the wreath represented authority and glory.********* The wreath was also imbued with divine authority. As Classical literature recites, gods wore this headdress.**********

The Gauls’ plan to seize the wreath and consume it playfully undermines its authority. The headdress is "hunted" in an unpremeditated way; it seems like a child’s amusement or sport. The plan is hatched during an egotistical and childish quarrel between Abraracourcix (Vitalstatistix) and his brother-in-law. Arguably, the dispute between these characters represents the power struggles on a micro-scale in the Celtic world after the Roman invasion. Vitalstatistix represents the traditional Gaul chief, whose power was established and maintained through circulation of goods and feasting. Meanwhile, Homéopatix (Homeopathix) represents the rising elite in the post-conquest world, who benefitted from mercantile connections and trade, while also engaged in Roman-inspired practices. As an interrelated historical point, in the Gaulish context, the laurel wreath may symbolically represent a substitute for the human head. Notably, the Celts practiced head hunting, which involved the severing of the head after death, a practice which the Romans deemed barbaric.*********** The symbolism of this practice is closely related to hunting.************ Greek literary sources reported that the heads of high-ranking officials were taken during battle and their heads were ‘impaled on spears.************* Later, they were preserved, kept in boxes and at times, displayed at the entrances of temples (see also Fliegel 1990)**************. The antics of Asterix and Obelix perpetuate the playful and childish nature of the scheme, especially when they are assigned as cooks in Quiquilfus (Humerus)’ kitchen. Overall, the scheme to steal the wreath not only mocks the Roman’s authority, but also suggests that through child-like play, amusements and games, one can break the shackles of domination and oppression.

Later, Caesar’s military victories are also undermined through the subversion of the symbol during the ceremonial procession. In the Roman world, the wreath was presented in a ceremonial procession, known as the Triumph. Military leaders who had been successful in campaigns were presented the wreath during the procession. From a mythological perspective, this presentation could be interpreted as a "seizing" the power of the other, just as Apollo seized Daphne after her attempted escape. In the story, the Roman triumph is organised for Caesar when he defeats the pirates. At the moment of his adornment, even though he feels like "fish", Caesar fails to recognise that he is wearing a fake replica. At this point, the authors subtly suggest that his authority is "as fake" as the wreath he adorns. He is not all-powerful, but has a "fishy" or suspect character.

Finally, the story also mocks and subverts the Roman juridical system. Arrested for the attempted murder of Caesar, the Gauls are committed to trial. The Roman legal system developed over a long period***************. By the time Caesar became proconsul, it had evolved into the formulary system, where the power of magistrates and courts was growing. The proceedings began when the plaintiff issued the defendant a summons to appear in court. Then, the magistrate heard the complaint to determine whether the matter would then be heard by a judex, a prominent authority, who was neither a lawyer nor magistrate****************. Asterix and Obelix’s trial is presented before a judge. When found guilty, the Gauls are condemned to death in the arena by wild lions. This type of Roman capital punishment was called the damnatio ad bestias and was a spectator sport held in the colosseum.***************** Importantly, the amphitheatre is called the "Circus Maximus" in the story and this highlights the entertainment aspect of the punishment. Furthermore, the event is referred to as a "show" (Goscinny and Uderzo 2012, p. 137). Asterix makes a farce of the proceedings when he pleads guilty and begs to be sentenced. He argues that the judge should send him straight away to the circus because the wild but "harmless" animals should not suffer. As he highlights, they should not be "punished" (Goscinny and Uderzo 2012, pp. 139–140). His arguments are reminiscent of animal rights activists. They evoke sympathy in the audience and the judge, who then sentences them in order to "save the wild animals" from hunger. This spectacle ridicules the Roman process, which was founded on evidence, reason and logic.

This narrative affords readers an opportunity to reflect on the structure and complex nature of power relationships in both the ancient and modern world. In particular, it can be used to inspire discussion about the ways the physical, emotional and intellectual capacities of individuals and groups are harnessed and controlled in systems, such as slavery, and how these can be subverted.

* Thomas Wiedemann, Greek and Roman Slavery, London, Routledge, 2003, 5, 8.

** Ibidem, 6.

*** Ibidem, 8.

**** Katharine Raff, “The Roman Banquet” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000 (accessed: January 29, 2021).

***** Ibidem.

****** Nancy Delucia Real, “The art of feasting in Roman Gaul. A glimpse at life in the ancient Roman provinces of Gaul through the lens of food, glorious food”, Getty. Iris Blog, published November 1, 2014 (accessed: January 29, 2021).

******* Analysis based on: R. Goscinny and A. Uderzo, “Asterix and the Laurel Wreath” in Asterix Omnibus 6. London: Orion Children’s, 2012, 107–152.

******** Dauriil Alden and Joseph C. Miller, “Out of Africa: The Slave Trade and the Transmission of Smallpox to Brazil (1560) 1831”, The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 18(2), 1987: 195–224.

********* Emilie Carruthers, “The Ancient Origins of the Flower Crown. From symbol of victory to Snapchat filter, wreaths of leaves and flowers have had symbolic meaning in Western culture for over 2,000 years”, Getty, Iris Blog, published May 4, 2017 (accessed: January 29, 2021).

********** Ibidem.

*********** Stephen Fliegel, “A Little-Known Celtic Stone Head”, The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 77. 3 (1990): 82–103, 89.

************ Miranda Green, Animals in Celtic Life and Myth, London Routledge, 1992, 63–64.

************* Stephen Fliegel, op.cit., 89.

************** Ibidem.

*************** The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, Roman legal procedure and legal system, britannica.com, revised by Brian Duignan (accessed: January 29, 2021).

**************** Ibidem.

***************** Tom Mueller, "Rome. The Secrets of the Colosseum”, Smithsonian Magazine, published January 2011 (accessed: January 29, 2021).

Further Reading

Alden, Dauril and Joseph C. Miller,“Out of Africa: The Slave Trade and the Transmission of Smallpox to Brazil (1560) 1831”, The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 18.2 (1987): 195–224.

Carruthers, Emilie, “The Ancient Origins of the Flower Crown. From symbol of victory to Snapchat filter, wreaths of leaves and flowers have had symbolic meaning in Western culture for over 2,000 years”, Getty, Iris Blog, published May 4, 2017 (accessed: January 29, 2021).

Delucia Real, Nancy, “The art of feasting in Roman Gaul. A glimpse at life in the ancient Roman provinces of Gaul through the lens of food, glorious food”, Getty. Iris Blog, published November 1, 2014 (accessed: January 29, 2021).

Fliegel, Stephen, “A Little-Known Celtic Stone Head”, The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 77. 3 (1990): 82–103, 89.

Green, Miranda, Animals in Celtic Life and Myth, London Routledge, 1992.

Mueller, Tom, "Rome. The Secrets of the Colosseum”, Smithsonian Magazine, published January 2011 (accessed: January 29, 2021).

Raff, Katharine, “The Roman Banquet” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000 (accessed: January 29, 2021).

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, Roman legal procedure and legal system, britannica.com, revised by Brian Duignan (accessed: January 29, 2021).

Wiedemann, Thomas, Greek and Roman Slavery, London, Routledge, 2003.

Addenda

Entry based on: R. Goscinny and A. Uderzo, “Asterix and the Laurel Wreath” in Asterix Omnibus 6, London: Orion Children’s, 2012, 107–152.