Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Anna Gkoutzouri, Θησέας και Μινώταυρος [Thīséas kai Minṓtavros], My First Greek Myths [Η μικρή μου μυθολογία (Ī mikrī́ mou mythología)]. Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2019, 10 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Pop-up books

Target Audience

Children

Cover

Courtesy of the publishing.

Author of the Entry:

Charlotte Farrell, University of New England, charlottefarrell@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

The author with her dog Lola. Courtesy of the Author.

Anna Gkoutzouri (Author)

Anna Gkoutzouri is a children's book illustrator, author, designer, and architect based in Greece. She received a Bachelor degree in 2003 in Civil Engineering at the Alexander Technological Educational Institute of Thessaloniki, and a Diploma in Architecture at Aristotle University in 2009. Her background in architecture informs the pop-up elements of her books, as well as her particular interest in how paper engineering can aid and inform young readers' engagement with complex issues. In addition to the "My First Greek Myths" series, Gkoutzouri also published My First Aesop Fables with Faros Books. Both series were originally published in Greek by Papadopoulos Publishing.

Sources:

farosbooks.co.uk (accessed: April 8, 2021),

gr.linkedin.com (accessed: April 8, 2021).

Bio prepared by Charlotte Farrell, University of New England, charlottefarrell@gmail.com

Translation

English: Theseus and the Minotaur, Faros Books, 2020, 10 pp.

Summary

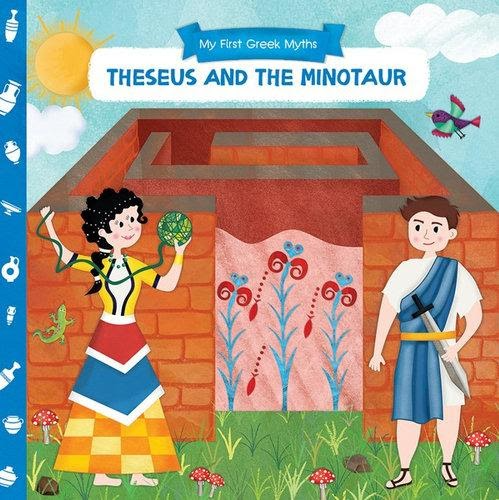

On the cover of this charming board book which has four double-page spreads in total, Ariadne stands with her string, ready to help Theseus who stands to her right. With the pull of a small lever, a Minotaur appears sandwiched between the two figures, waving a tiny toy drum. On the first page of the story we encounter Minos, who demands that he receive fourteen youths to serve him each year. Seven female-presenting youths are holding little boxes with the numbers 1–6 on them. When a lever on the middle of the page is moved the left, faces of seven presumably male youths is revealed, presenting an opportunity for the young reader to practice counting.

Theseus, prince of Athens, sails to Crete to put a stop to the slavery. He vows to change his sails to white if he survives. One can have a tactile interaction with Theseus sailing on this page, moving him up and down on the waves where he is accompanied by leaping dolphins, fish, and a seagull.

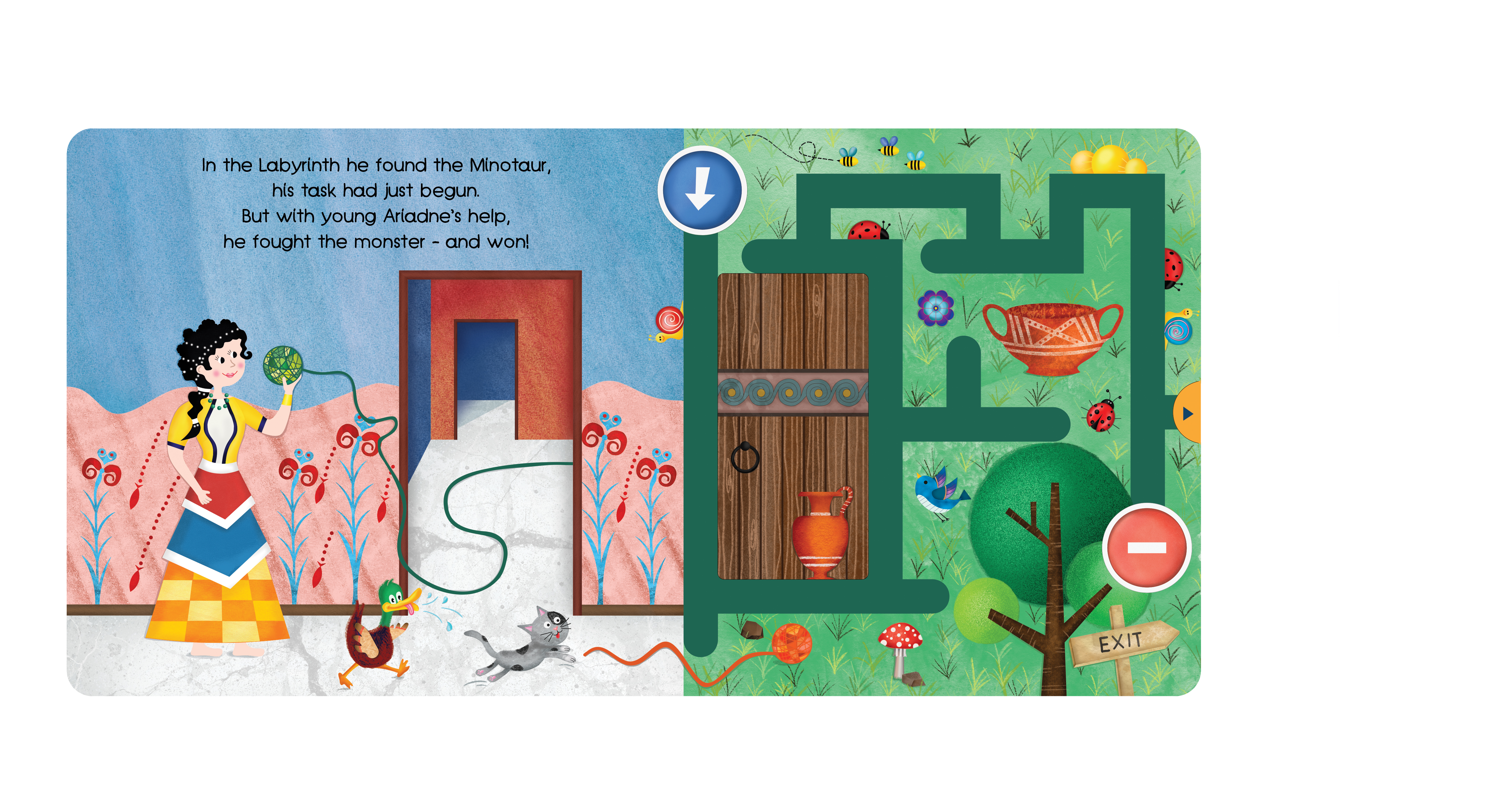

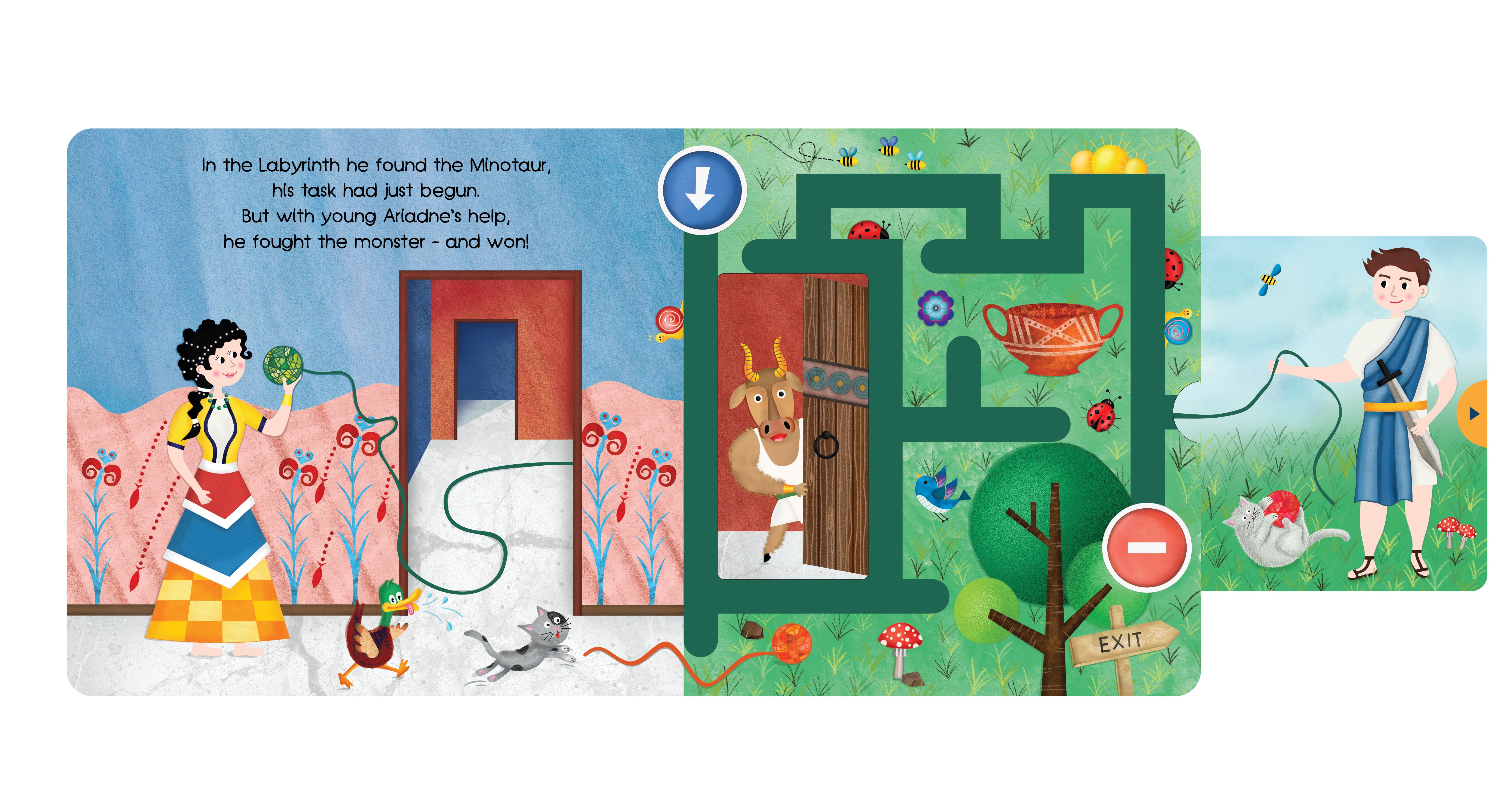

Theseus enters the labyrinth and because of the help of Ariadne’s thread, he is able to find and win against the Minotaur. Although victorious, on his journey back to Athens, Theseus forgets to change his sails from black to white. His father stands on a cliff at the edge of the city looking puzzled. The reader however can interfere with his ill luck by spinning the side lever which transforms the sails from black to white and back again.

Analysis

Arguably, through a feminist retelling, Ariadne could have been reframed as the hero of this story. The author, however, cements her as Theseus' helper. In the scene in the Labyrinth, Ariadne stands passively smiling and holding the thread. Theseus holds the other end of the thread at the Labyrinth's exit. He smiles and clutches his sword. Ariadne wears a long dress and jewels in her long, dark braided hair. She has long eyelashes and rosy cheeks. Gkoutzouri uses a traditional representation, with Theseus being a standard "masculine" hero and Ariadne a traditional pretty princess.

The book elides Theseus's abandonment of Ariadne. In the myth, Theseus left Ariadne on the Island of Naxos on his journey back to Athens. Omitting this from the book demonstrates the author's consideration of the age group of her readers, allowing for the parents or guardians to extrapolate on the missing elements as the children are older if desired.

In the original myth, when Theseus' father Aegeus sees the sails are black, he throws himself off the cliff. This is alluded to in the book and demonstrates the author's clever handling of the more brutal aspects of the myth, which are inappropriate for the age group for which the book is intended. By allowing for the reader's tactile engagement with this moment in the book, however, there is something hopeful in potentially transforming this aspect of the myth. This leaves one to wonder: What if Theseus did change the sails to white as he had promised his father?

Further Reading

Weinlich, Barbara, "The Metanarrative of Picture Books: ‘Reading’ Greek Myth for (and to) Children)", in Lisa Maurice, ed., The Reception of Ancient Greece and Rome in Children’s Literature: Heroes and Eagles, Leiden: Brill, 2015, 85–104.

Weinstein, Amy, Once Upon a Time: Illustrations from Fairytales, Fables, Primers, Pop-ups and Other Children’s Book, Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 2005.

Addenda

This entry is based on the English edition (2020).

Courtesy of Anna Gkoutzouri.