Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Anna Gkoutzouri, Ηρακλής [Īraklī́s], My First Greek Myths [Η μικρή μου μυθολογία (Ī mikrī́ mou mythología)]. Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2019, 10 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Pop-up books

Target Audience

Children

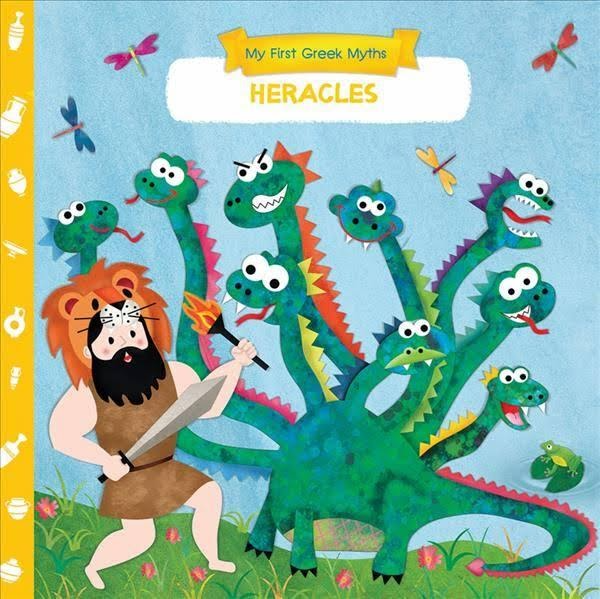

Cover

Courtesy of the publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Charlotte Farrell, University of New England, charlottefarrell@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

The author with her dog Lola. Courtesy of the Author.

Anna Gkoutzouri (Author)

Anna Gkoutzouri is a children's book illustrator, author, designer, and architect based in Greece. She received a Bachelor degree in 2003 in Civil Engineering at the Alexander Technological Educational Institute of Thessaloniki, and a Diploma in Architecture at Aristotle University in 2009. Her background in architecture informs the pop-up elements of her books, as well as her particular interest in how paper engineering can aid and inform young readers' engagement with complex issues. In addition to the "My First Greek Myths" series, Gkoutzouri also published My First Aesop Fables with Faros Books. Both series were originally published in Greek by Papadopoulos Publishing.

Sources:

farosbooks.co.uk (accessed: April 8, 2021),

gr.linkedin.com (accessed: April 8, 2021).

Bio prepared by Charlotte Farrell, University of New England, charlottefarrell@gmail.com

Translation

English: Heracles, Faros Books, 2020, 10 pp.

Summary

Heracles is part of the "My First Greek Myths" board book series by Anna Gkoutzouri. The book features interactive levers that allow you to push, pull, and slide palimpsestic images revealing various characters from the Heracles myth. These reveals also allow for playful plot developments. There are four, thick double-page spreads in total in the book. In the cover image, Heracles is flanked in a characteristic lion’s mane, bearing a sword and fiery torch. He approaches what is presumably the nine-headed Lernaean Hydra. The cover has a playful feature where readers can spin the monster's heads in circles – a feature that recurs delightfully throughout the book for tactile engagement for baby readers.

The book begins by introducing baby Heracles who is taking a bath and playing with two small snakes delivered to him from Hera. The following page skips ahead to when Heracles is older. In this book's account, a king asked him for a favour, which takes the form of Heracles' twelve labours. Heracles was tasked to perform a range of incredible feats. The vivid and brightly coloured illustrations capture Heracle' strength while undertaking these challenges. A gigantic lion and heads of the Lernaean Hydra have little yellow stars spinning around them, presumably after being smacked with the large club that Heracles dangerously wields. The readers are able to push Heracles' club up and down themselves to playful effect.

Emerging victorious, wearing the slain lion's head upon his own head on the following page, Heracles continues his labours. He carries what appears to be the globe on his shoulders, alluding to when he relieves Atlas of his world-carrying duties in the original myth. Again, there is a tactile function where the reader can turn the apples on the apple tree from gold to red and vice versa. This illustrates the snatching of the golden apples that Heracles must complete as part of the twelve labours, allowing the reader to engage with the act themselves.

The book concludes with Heracles triumphant before the King. He is presented with an elaborate celebratory feast replete with ice cream, candy, burgers, pizza, and a steaming roast chicken to mark Heracles' completion of the twelve labours and subsequent ascent to Olympus. The reader can spin the items on the table around in a manner akin to a lazy susan or Chinese dinner-table turntable.

Analysis

This book's tactile functions and brightly coloured illustrations bring Heracles' twelve labors vividly to life. The use of four-line rhyme scheme throughout successfully animates the story for young readers. Some of the labors, however, are omitted for the book. Heracles does not obtain Hippolyta's girdle, and there is no slaying of the man-eating Stymphalian birds. Clearly Hippolyta's girdle would be difficult to communicate to a baby reader for whom this book is intended, and the same could be said for the birds. The violence that remains in the book, however, particularly in the slaying of the lion and the multiple-headed monster, is presented in such a way that is suitable for babies. This is achieved through implied rather than illustrated violence, such as the small stars spinning cartoonishly around the animals' heads after Heracles has hit them.

Due to the limitations of space in this short book, the potential to vividly capture each of the labours is condensed. This means that Cerberus, for example, is illustrated as a small domestic dog with three heads, a spiky collar, and a bone, while the book does not demonstrate Heracles' defeat of the beast. On the same page, the wild horses Heracles tamed are illustrated through a single grazing farm horse. While the allusions to the details of the myth make sense for its length, and violent or dark elements are glossed over, there is certainly something lost in the book's condensed length. A slightly longer version would enable more of the wonderful illustrations already included, and elaboration of Heracles' twelve labours. On the other hand, condensing the labours allows for the issue of representing the violence to young readers more suitable for the age group.

There is room for the book's meaning to grow with the child's development. Adults with more knowledge of the myths are able to convey the book's witty double-coding to children, while babies may simply enjoy playing with the engaging tactile aspects. The truth behind Heracles wearing the lion's head which symbolises his defeat of the animal, for example, would certainly be an amazing revelation for the child reader. Likewise, being able to turn the Apples of the Hesperides on the tree from red to gold and vice versa through the push-and-pull interactive function would make for an effective tool to discuss different versions of the myth: did Heracles slay a dragon to obtain the apples; did Atlas take the apples for him; or did he manipulate Hesperides to give him the apples freely? There are several instances of the author's clever double coding throughout the book, engaging baby, children, and adult readers alike.

Further Reading

Weinlich, Barbara, "The Metanarrative of Picture Books: ‘Reading’ Greek Myth for (and to) Children)", in Lisa Maurice, ed., The Reception of Ancient Greece and Rome in Children’s Literature: Heroes and Eagles, Leiden: Brill, 2015, 85–104.

Weinstein, Amy, Once Upon a Time: Illustrations from Fairytales, Fables, Primers, Pop-ups and Other Children’s Book, Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 2005.

Addenda

This entry is based on the English edition (2020).