Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Details

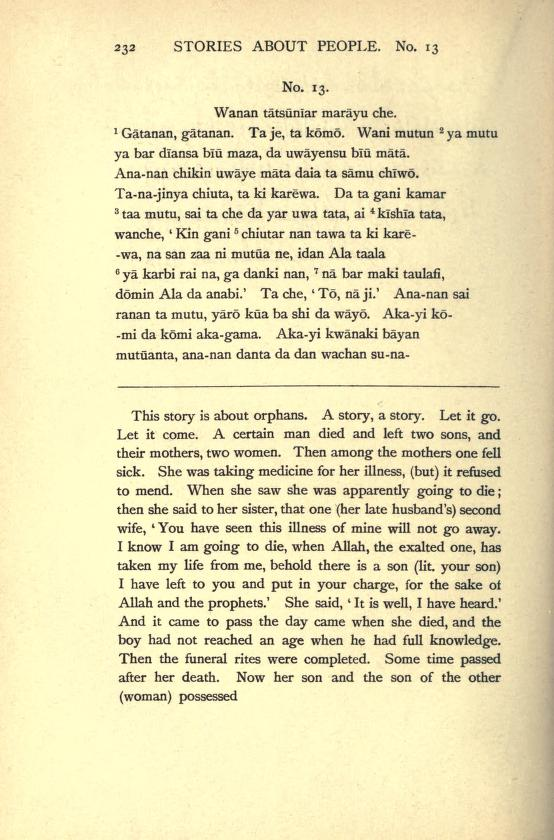

Robert Sutherland Rattray, "A Story about an Orphan Which Was the Origin of the Saying The Orphan with a Coat of Skin is Hated, but When It Is a Metal One He Is Honoured”, in Hausa Folk-Lore: Customs, Proverbs, etc. Collected and Transliterated with English Translation and Notes. Vol. 1, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913, 232–247.

Available Onllne

A Story about an Orphan Which Was the Origin of the Saying: "The Orphan with a Coat of Skin is Hated, but When It Is a Metal One He Is Honoured" (accessed: July 2, 2021).

Genre

Folk tales

Target Audience

Crossover

Cover

Retrieved from Internet Archive (accessed: July 2, 2021).

Author of the Entry:

Chester Mbangchia, University of Yaoundé 1, mbangchia25@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaoundé 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elżbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Robert Sutherland Rattray

, 1881 - 1938

(Author)

Robert Sutherland Rattray (1881–1938) was born in India. He was a Scottish anthropologist and an authority on the native peoples of West Africa. He was educated at Exeter College at Oxford University and held a diploma in anthropology. In 1902 he entered Civil Service in Africa, first, in British Central Africa and from 1907, on the Gold Coast. During the Great War he served in Togoland and received the MBE, in 1929, he was progressed to CBE. In each place he was sent to, he studied local languages and conducted anthropological research about folklore, religion, beliefs, customs, law, art, folktales and proverbs. In 1924 he was made head of the Anthropological Department in Ashanti/Asante in acknowledgment of his merits. His contribution to the detailed study of the Ashanti customs and folklore was based on personal observations, contacts with the Ashanti, and a thorough knowledge and understanding of their culture. On his retirement, R. S. Rattray was a lecturer of anthropological topics at Oxford and elsewhere. He was passionate about flying, one of the first to fly to West Africa, a pioneer of gliding. He founded a club of gliding at Oxford and a week later was killed in a glider flying accident.

His main works include: Some Folk-Lore Stories and Songs in Chinyanja: with English Translations and Notes (1907), Hausa Folk-Lore, Customs, Proverbs, etc.: Collected and Transliterated with English Translation and Notes (1913), Ashanti Proverbs: the primitive ethics of a savage people: translated from the original with grammatical and anthropological notes (1916), An Elementary Mōle Grammar with a Vocabulary of Over 1000 Words for the Use of Officials in the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast (1918), Ashanti (1923), Ashanti Law and Constitution (1929), Akan-Ashanti Folk-tales (1930), The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland (1932), The Golden Stool of Ashanti: a Sacred Shrine Regarded as a Symbol of the Nation's Soul, and Never Lost or Surrendered, Its True History, a Romance of African Colonial Administration (1935).

Source:

“Captain R. S. Rattray, C. B. E.”, Nature 3577.141 (1938): 904, 929. (accessed: July 2, 2021).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolinska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Maalam Shaihu (Author)

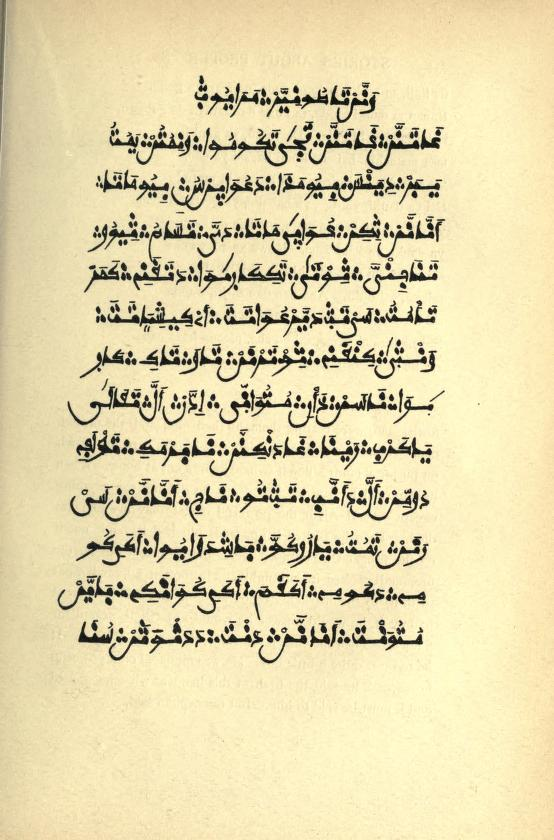

Maalam Shaihu (active in the early twentieth century) was one of the learned Hausas known as maalamai, who were the most respected and honoured members of the Hausa community in the Gold Coast and Nigeria. The use of Arabic corresponded at that time to the use of Latin in mediaeval Europe, the knowledge of Arabic was necessary for conducting any research about the Hausa culture. A maalam of the best class possessed all the language and literary skills and understanding of the Hausas. Thus, Shaihu cooperated with R. S. Rattray to gather Hausa stories and manuscripts and make the Hausa culture better known. Much of the work contained in Hausa Folk-Lore involved his translation from Arabic into Hausa, and Rattray’s translation into English from the Hausa. In 1907-1911 during Rattray’s journeys in West Africa and in England, Maalam Shaihu accumulated many hundreds of sheets of manuscripts. Thanks to his work the traditional lore lost nothing of its authenticity. It is worth mentioning that, by the grant of the government of the Gold Coast, Maalam Shaihu’s Arabic penmanship was preserved by facsimile reproduction of his Arabic text printed in the 1913 edition.

Source:

R. R. Marett, Preface; R. Sutherland Rattray, Author’s Note in R. S. Rattray, Hausa Folk-Lore, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913.

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Summary

There was a man who died and left two sons and their mothers, his wives. Time passed, and one of the mothers fell sick. No matter the quantity and quality of medicine that she took, there was no amelioration. Realizing that she would die, she swore in the name of God and told the other woman that she was leaving her son for her to take care of. The other woman (i.e. co-wife) accepted this agreement. One day, she died, and when the funeral was over, her son started rearing fowls with his half-brother, the other woman's (co-wife's) son. One day, when the orphan boy was not at home, the co-wife lifted a stick and killed one of the orphan boy's fowls. On his return, the boy saw his fowl down and prayed to God to help him. He plucked the fowl, prepared it, took it to the market to sell. In the market, the chief's favourite little son arrived on a powerful horse, admired the flesh of the fowl and exchanged his horse for the fowl flesh. When the orphan boy returned home with the horse, his stepmother (co-wife) asked him to keep the horse in a locked room and that after seven days, he will open the door and see that the horse will have grown. In reality, she wanted the horse to starve to death, but the little boy did not know, and so he kept the horse in the locked room. When he unlocked the door after seven days, he saw that the horse had grown fat. His stepmother (co-wife) was angry because the horse was still alive. One day, the stepmother told the orphan boy to sell the horse and use the money to buy grain stalk for the household because there was no food. The boy refused to do so, and she shouted at him. Finally, the orphan boy gave in and sold the horse and bought the grain stalk. However, the stepmother burnt the grain.

Three little pieces of the stalk survived the fire; the little boy kept them in a small bag. Once he climbed a fetish altar in a town and was caught, his throat was about to be cut. He told his attackers that they should not kill him if they wanted him to heal the sick chief. They accepted and allowed him to try and heal the chief. He then burnt the three grain stalks that had survived the fire to heal the chief. The chief was happy and assembled all the people to tell them of the boy who healed him. He said he was to give the boy half of his land to rule, but the boy objected, saying that he was only a trader and would not want to rule. The chief asked him to take whatever pleased him. He took slaves, cattle and other beautiful things with which to start his life. Before he went, his stepmother asked him to help her hunt rats for her to make soup. He assured her that he can offer her guinea-fowls, hens and rams, but she insisted on rats. He accepted and asked her to take him to where he could find rats. She planned to take him where there was a snake hole so that he would get bit. One of the boy's slaves opted to help his master in the digging, but the woman stopped the slave. The boy himself decided to do the task, and she asked him to put his hoe down and instead put his hands in the hole.

When he put his hands in, he brought out a golden bracelet and a golden bangle. Infuriated, the woman asked the boy to put his hands in another hole. In this next hole, she also asked her own son to help so that he could find a bracelet too. Unfortunately, it was in this hole that her son found a snake. When he put his hand in, the snake bit him. He died before they arrived home. The woman died three days later from depression. The orphan inherited the woman's properties, and this incident generated the saying, 'the orphan with the cloak of skin is hated, but when it is a metal one, he is looked on favourably.'

Analysis

This Ghanaian myth falls into the category of myths about the suffering of orphans at the hands of their wicked stepmothers and how through obedience, hard work and perseverance, orphans can finally obtain wealth, fame and/or power. It replicates the stereotype of the wicked step- and foster mothers. Humanity has often witnessed the coming to power of children mistreated by their stepmothers. The stepmother's schemes in this myth against the boy and the boy's gaining of fame and wealth parallel the suffering Cinderella underwent with her stepmother. The general motif of the jealous, murderous, witchy stepmothers, seen in other mythologies, who lead their stepchildren to heroism, extends to African myths. Also, favouring their own children over their stepchildren is a universal theme present in many cultures.

Further Reading

Climo, Shirley, and Ruth Heller, The Egyptian Cinderella, New York: Crowell, 1989.

Joseph, Michael Scott, “Myth of the Golden Age: Journey Tales in African Children’s Literature”, Contributions in Afro-American and African Studies 187 (1998): 17–130.

Addenda

Although these myths were collected so many years ago, they are still being told to children and young adults in traditional African communities. And like all other oral narratives, several versions of the same story may be available in different places.

The first edition of Hausa Folk-Lore was published in English by Clarendon Press, providing, the text of the stories in three languages simultaneously: Hausa, English and Arabic, as it was an academic publication aimed at anthropologists, students and Hausa language learners (especially that it contains pronunciation tables at the beginning, and some notes with vocabulary and grammar at the end of vol. 2).

Even though Rattray aimed his book at students of the Hausa language and anthropologists, after his death it was republished many times without Hausa and Arabic text as interesting Hausa stories to be told, while the oral versions of the folk tales were still alive. It shows two parallel ways of the reception of these folktales which are worth highlighting.

Scans retrieved from Internet Archive (accessed: July 2, 2021).