Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Details

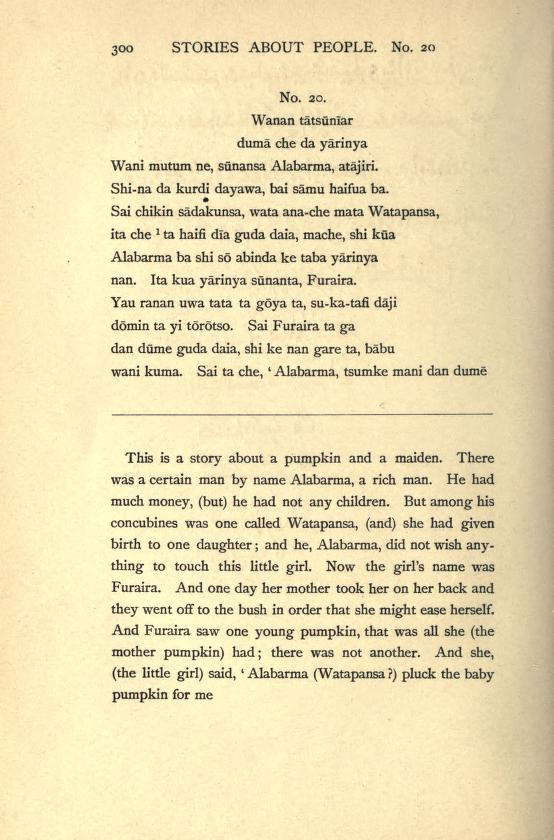

Robert Sutherland Rattray, "A Story about a Maiden and the Pumpkin” in Hausa Folk-Lore: Customs, Proverbs, etc. Collected and Transliterated with English Translation and Notes. Vol. 1, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913, 300–311.

Available Onllne

A Story about a Maiden and the Pumpkin (accessed: July 5, 2021)

Genre

Folk tales

Target Audience

Crossover

Cover

Retrieved from Internet Archive (accessed: July 2, 2021).

Author of the Entry:

Eleanor A. Dasi, University of Yaoundé 1, wandasi5@yahoo.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaoundé 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Robert Sutherland Rattray

, 1881 - 1938

(Author)

Robert Sutherland Rattray (1881–1938) was born in India. He was a Scottish anthropologist and an authority on the native peoples of West Africa. He was educated at Exeter College at Oxford University and held a diploma in anthropology. In 1902 he entered Civil Service in Africa, first, in British Central Africa and from 1907, on the Gold Coast. During the Great War he served in Togoland and received the MBE, in 1929, he was progressed to CBE. In each place he was sent to, he studied local languages and conducted anthropological research about folklore, religion, beliefs, customs, law, art, folktales and proverbs. In 1924 he was made head of the Anthropological Department in Ashanti/Asante in acknowledgment of his merits. His contribution to the detailed study of the Ashanti customs and folklore was based on personal observations, contacts with the Ashanti, and a thorough knowledge and understanding of their culture. On his retirement, R. S. Rattray was a lecturer of anthropological topics at Oxford and elsewhere. He was passionate about flying, one of the first to fly to West Africa, a pioneer of gliding. He founded a club of gliding at Oxford and a week later was killed in a glider flying accident.

His main works include: Some Folk-Lore Stories and Songs in Chinyanja: with English Translations and Notes (1907), Hausa Folk-Lore, Customs, Proverbs, etc.: Collected and Transliterated with English Translation and Notes (1913), Ashanti Proverbs: the primitive ethics of a savage people: translated from the original with grammatical and anthropological notes (1916), An Elementary Mōle Grammar with a Vocabulary of Over 1000 Words for the Use of Officials in the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast (1918), Ashanti (1923), Ashanti Law and Constitution (1929), Akan-Ashanti Folk-tales (1930), The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland (1932), The Golden Stool of Ashanti: a Sacred Shrine Regarded as a Symbol of the Nation's Soul, and Never Lost or Surrendered, Its True History, a Romance of African Colonial Administration (1935).

Source:

“Captain R. S. Rattray, C. B. E.”, Nature 3577.141 (1938): 904, 929. (accessed: July 2, 2021).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolinska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

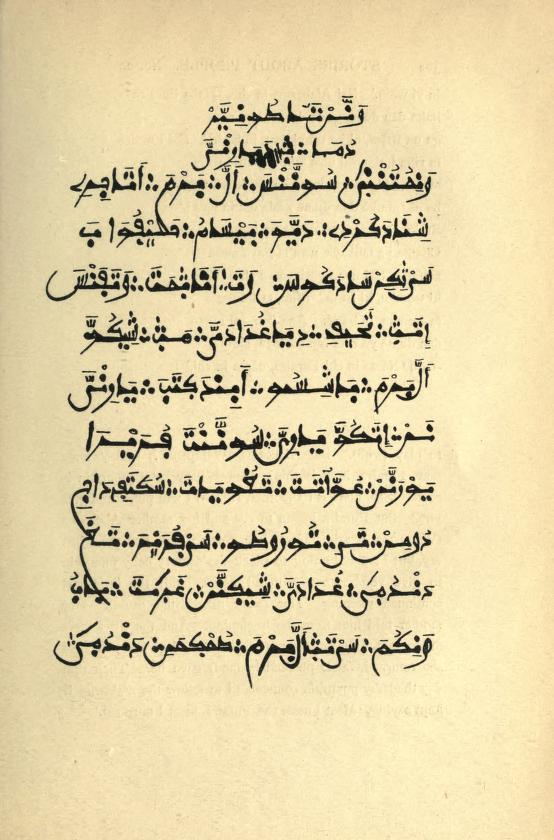

Maalam Shaihu (Author)

Maalam Shaihu (active in the early twentieth century) was one of the learned Hausas known as maalamai, who were the most respected and honoured members of the Hausa community in the Gold Coast and Nigeria. The use of Arabic corresponded at that time to the use of Latin in mediaeval Europe, the knowledge of Arabic was necessary for conducting any research about the Hausa culture. A maalam of the best class possessed all the language and literary skills and understanding of the Hausas. Thus, Shaihu cooperated with R. S. Rattray to gather Hausa stories and manuscripts and make the Hausa culture better known. Much of the work contained in Hausa Folk-Lore involved his translation from Arabic into Hausa, and Rattray’s translation into English from the Hausa. In 1907-1911 during Rattray’s journeys in West Africa and in England, Maalam Shaihu accumulated many hundreds of sheets of manuscripts. Thanks to his work the traditional lore lost nothing of its authenticity. It is worth mentioning that, by the grant of the government of the Gold Coast, Maalam Shaihu’s Arabic penmanship was preserved by facsimile reproduction of his Arabic text printed in the 1913 edition.

Source:

R. R. Marett, Preface; R. Sutherland Rattray, Author’s Note in R. S. Rattray, Hausa Folk-Lore, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913.

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Summary

There was once a rich man called Alabarma, whose wife, Watapansa gave birth to a girl called Furaira; the man decided that he did not wish to raise a hand to her. One day Watapansa took Furaira to the bush to relieve herself. There, the child saw a pumpkin and asked her mother to harvest it for her to play with. Her mother refused because it was the sole pumpkin in the patch, and she did not want to disturb it. This made Furaira cry all the way home. Once there, the father asked the cause of her sadness and her mother described what happened. When he finished listening, he asked her to return to that place in the bush and pick the pumpkin. She did as her husband said, and Furaira was happy to have the pumpkin as a plaything. The pumpkin soon started asking Furaira to give it meat. Furaira told her father; he instructed her to put the pumpkin among the goats. And when she did, the pumpkin devoured three hundred and fifty goats. After that, it returned to Furaira and asked for more meat. Confused, Alabarma asks her to put the pumpkin among the cattle kraal. In the sheep-fold, the pumpkin devoured seven hundred sheep and still asked for more meat. When it was taken to the village, it devoured all the people and asked for more meat. They decided to take it into the slave quarters, and it ate them up too, and still asked for more meat. At this point, Alabarma says to take the pumpkin to the grazing ground. Once there, it ate up all the people and still asked Furaira for more meat. When it had eaten all the people, cattle, sheep, horses, guinea-fowls, ducks, and everything else, there only remained only the master of the house. Furaira, having escaped, Alabarma asks the pumpkin to eat him. The baby pumpkin swallows him and goes after Furaira, who hid herself with her father's paschal ram. When the pumpkin came in search of her, the ram struck it with its horn, and all the cattle, goats, sheep and everything it had swallowed came back out.

Analysis

Single children have most often posed a problem to society since they are often naughty and spoiled by their parents. These parents usually give these children everything they need, and sometimes, forbidden things. In this myth, Furaira is an example of a naughty single child who forces her parents to succumb to her whims and caprices. Furaira's incessant demand for the lone pumpkin as a plaything brings calamity to the family and society. Her mother's attempt to protect the pumpkin also echoes the human desire to protect nature, despite her daughter's plea to cut the plant.

The reversal of fortune that Alabarma faces is because of his pride as a father, who thinks that his daughter should have anything she requests because he is rich. Finally, the myth serves as a warning to parents who give their children everything as they may fall prey to disaster. It also highlights the vices of naughtiness and capriciousness in children as these may have devastating consequences on both on family and society.

Further Reading

Bivins, Mary Wren, Telling Stories, Making Histories: Women, Words, and Islam in Nineteenth-Century Hausaland and the Sokoto Caliphate, Portsmouth: Heinemann, 2007.

Haour, Anne and Benedetta Rossi, eds., “Being and Becoming Hausa: Interdisciplinary Perspectives”, African Social Studies Series, Boston: Leiden Brill, 2010.

Salamone, Frank A., The Hausa of Nigeria, Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2010.

Addenda

Although these myths were collected so many years ago, they are still being told to children and young adults in traditional African communities. And like all other oral narratives, several versions of the same story may be available in different places.

The first edition of Hausa Folk-Lore was published in English by Oxford Clarendon Press, providing, however, the text of the stories in three languages simultaneously: Hausa, English and Arabic as it was an academic publication aimed at anthropologists, students and Hausa language learners (especially that it contains pronunciation tables at the beginning, and some notes with vocabulary and grammar at the end of vol. 2).

Even though Rattray aimed his book at students of the Hausa language and anthropologists, after his death it was republished many times without Hausa and Arabic text as the interesting Hausa stories to be told, while the oral versions of the folk tales were still alive. It shows two parallel ways of the reception of these folktales and this is a phenomenon which is worth being highlighted.

Scans retrieved from Internet Archive (accessed: July 5, 2021).