Title of the work

Studio / Production Company

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Dead Poets Society. Directed by Peter Weir. Touchstone Pictures Silver Screen Partners IV, Buena Vista Pictures Distribution, 1989, 129 min.

Running time

Format

Date of the First DVD or VHS

Awards

1989 – BAFTA Award for Best Film and Best Original Film Score;

1990 – Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay;

1990 – David di Donatello Award for Best Foreign Film;

1991 – César Award for Best Foreign Film.

Genre

College life films

Drama

Motion picture

Target Audience

Young adults

Cover

We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover.

Author of the Entry:

Zofia Kowalska, University of Warsaw, z.kowalska4@student.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Tom Schulman

, b. 1951

(Scriptwriter)

Tom Schulman was born in Nashville, Tennessee in 1951. He graduated in philosophy at Vanderbilt University, located in his hometown. After that he moved to Los Angeles to attend USC Film School. He resigned after two semesters and started working in educational films and theatre. Schulman has written and co-written numerous scripts, such as Honey, I Shrunk the Kids (1989), Second Sight (1989), Holy Man (1989), What about Bob? (1991) and Welcome to Mooseport (2004). He also produced the movie Indecent Proposal (1993) and directed 8 Heads in a Duffel Bag (1997). In 2009 he was elected vice president of the Writers Guild of America, West (WGAW). Schulman remains best known for his semi-autobiographical screenplay Dead Poets Society, which won the Best Screenplay Academy Award in 1989.

Sources:

McCurrie, Tom, Dead Poet Society’s Tom Schulman on the art of surviving Hollywood, Writers SuperCentre, 2004 (accessed: September 14, 2022).

Tom Schulman Biography at filmreference.com (accessed: September 14, 2022).

Bio prepared by Zofia Kowalska, University of Warsaw, z.kowalska4@student.uw.edu.pl

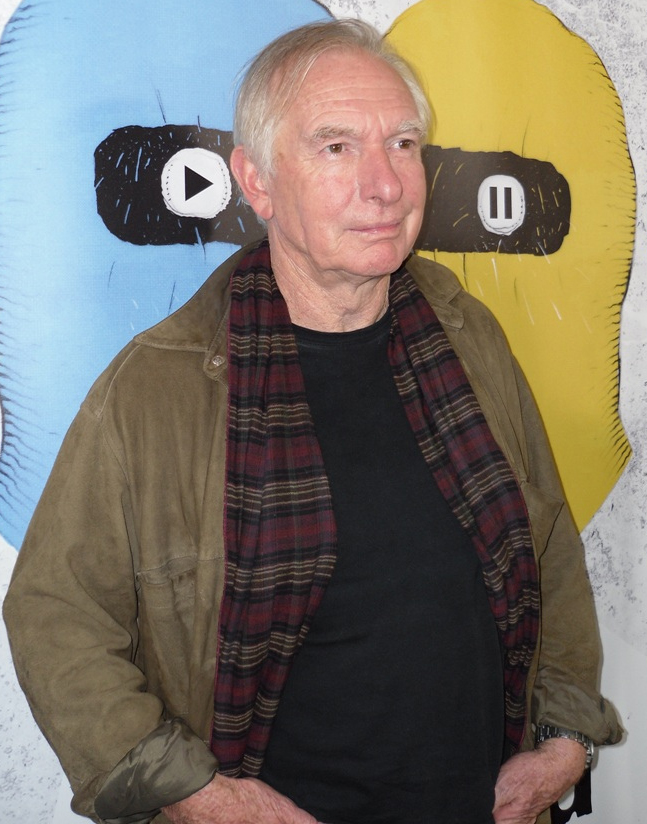

Peter Weir in 2011 at an independdent film festival in Cracow. Photograph by Piotr Drabik retrieved from Wikimedia Commons (accessed: September 14, 2022).

Peter Weir

, b. 1944

(Director)

Peter Weir was born in Sydney in 1944. He attended Vaucluse Boys’ High School and The Scots College before studying arts and law at the University of Sydney. His passion for film began during his time at the university, when he met a group of fellow students, including Phillip Noyce and future members of the Sydney filmmaking collective Ubu Films. After that he dropped out of the university and worked as a real estate seller for two years in order to make enough money to afford sailing to England with several friends. During their trip Weir and his companions found an unused closed-circuit television camera and created revues and entertainments for other passengers. When they returned to Sydney in 1966, Weir was determined to become a filmmaker. He started his career as a stagehand at Channel 7 television, after that he directed two short films: Count Vim’s Last Exercise (1968), The Life and The Times of the Reverand Buck Shotte (1968). In the ‘70s Weir became a leading figure in the Australian New Wave cinema movement with films such as Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), The Last Wave (1977) and Gallipoli (1981). Since then Weir has directed various movies including The Year of Living Dangerously (1983) Witness (1985), Dead Poets Society (1989), Green Card (1998) and The Truman Show (1998). For his work, Weir has received six Academy Award Nominations as either a director, writer or producer.

Sources:

Champlin, Charles, “Peter Weir: In a Class by Himself: Disney gambles that summer audiences will tire of sequels and look for more challenging fare”, Los Angeles Times, June 4, 1989 (accessed: September 14, 2022).

Peter Weir Biography at filmreference.com (accessed: September 14, 2022).

Tibbetts, John C., “In Search of Peter Weir”, Journal of Popular Film and Television, 41.4 (2013), 170–180 (accessed: September 14, 2022).

Bio prepared by Zofia Kowalska, University of Warsaw, z.kowalska4@student.uw.edu.pl

Casting

Robin Williams as John Keating,

Robert Sean Leonard as Neal Perry,

Ethan Hawke as Todd Anderson,

Josh Charles as Knox Overstreet,

Gale Hansen as Charles Dalton,

Norman Lloyd as Mr. Nolan,

Kurtwood Smith as Mr. Perry,

Dylan Kussman as Richard Cameron,

James Waterson as Gerard Pitts,

Allelon Ruggiero as Steven Meeks.

Adaptations

Novel: Nancy H. Kleinbaum, Dead Poets Society, New York: Hyperion, 1989.

Theatrical adaptation written by Tom Schulman and directed by John Doyle in New York (from October 27, 2016 to December 11, 2016). More information at https://www.playbill.com/article/csc-to-stage-world-premiere-of-dead-poets-society, https://www.playbill.com/article/dead-poets-society-finds-its-complete-cast and https://www.playbill.com/article/the-world-premiere-of-dead-poets-society-begins-tonight# (accessed: April 11, 2020, no longer active).

Summary

The action starts in the fall of 1959 when a new English teacher (a former student), John Keating, arrives at the Welton Academy – a very conservative boarding prep school for boys in Vermont, New England. His unorthodox teaching methods are meant to inspire students to think critically, become individuals and make their lives extraordinary. The Latin expression Carpe diem soon becomes the mantra for a group of boys who are fascinated with Keating’s approach to life. When they find out that he once belonged to the unsanctioned Dead Poets Society, they decide to “seize the day” and restart the club. They start sneaking off campus to a cave in the woods where they read poetry, including their own compositions.

A newly found passion for literature, as well as the idea of going against the status quo, encourages boys to make changes in their lives. One of the students, Todd, finds courage to speak for himself, while another one, Knox, confesses his feelings to the girl of his dreams. Neil, a fellow member of Dead Poets Society, decides to take a risk and follow his passion for acting. Not much later, he gets the role as Puck in a local production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In order to take part in the play he has to receive a written permission from his strict father, who refuses to allow him to pursue his passion. Neil forges the required letter and participates in rehearsals, leading to the performance. On the night of the premiere his father unexpectedly shows up at the theatre and forces his son to leave. At home he informs Neil that he has been withdrawn from Welton and from now on will be attending a military academy. The boy feels trapped and helpless, at this point he sees no future for himself. In the middle of the night he sneaks into his father offices, takes out a gun from a desk drawer and commits suicide.

Neil’s parents blame the English teacher for what happened to their son. One of the students, Cameron, states that Keating is responsible for Neil’s death and in the end all members of the Dead Poets Society sign a declaration, which indicates that the teacher must be fired. Headmaster Nolan replaces Keating and restores traditional Welton rules. During the first lesson he gives, the former English teacher enters the classroom to gather his leftover belongings. As he leaves, Todd stands up on his desk and says “O Captain! My Captain!”, referring to the Walt Whitman’s poem, which was cited by Keating during their first meeting at Welton. Other members of the Dead Poets Society follow his lead in order to pay respects and say goodbye to their extraordinary teacher.

Analysis

"Carpe diem. Seize the day, boys. Make your lives extraordinary!" – with these words Keating summarizes the first lesson he gives at Welton Academy. This anthemic line can be seen as a mantra, which returns repeatedly at key moments of the movie. Todd writes down Carpe Diem on a piece of paper, but soon after he throws it away and reaches for the textbook. This symbolic gesture shows his fear and insecurity as even when he is all alone, he cannot allow himself to do anything that goes against the “four pillars” of Welton: Tradition, Honor, Discipline, and Excellence. Later in the movie, when Neil decides to audition for a role in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, he says: "For the first time in my life, I know what I wanna do. And for the first time, I’m gonna do it! Whether my father wants me to or not. Carpe diem!" Similarly, when Knox dares to kiss the girl of his dreams, he whispers carpe diem, to give himself courage.

These famous words (that ranked among the American Film Institute’s 100 greatest movie quotes) have fundamental value for the members of the Dead Poets Society. Keating’s credo influences them more than anything else at the Academy and urges them to fight for the right to be themselves. It also proves the power of the word and shows how poetry and literature in general can change the world. It is surprising how deeply young people can be moved by a Latin aphorism, taken from book 1 of the Roman poet Horace’s work Odes, written over two thousand years ago (although some say that the first written expression of this poetic concept comes from the Epic of Gilgamesh, see Perdue, 2008, p.57). Nowadays, Dead Poets Society continues to resonate with teenagers 30 years after its theatrical release. Numerous tattoos are made under the influence of John Keating, as well as t-shirts, mugs, posters and more.

It is important to note that Keating’s translation of this famous line is not entirely correct. According to Maria S. Marsilio: "Carpe diem is a metaphor of the natural world that suggests the “plucking” of fruits or flowers" (Marsilio, 2010, p. 120). Though it may seem that these two metaphors have the same meaning, there are some major differences. “Seizing” sounds like a rather violent, immediate action, whereas "plucking" leaves time for reflection and peaceful enjoyment of the present moment. Perhaps Neil’s death and Charlie’s expulsion from school can be seen as consequences of this tragic misunderstanding. Keating did not promote recklessness or imprudence, all he wanted to teach the boys was to be individuals, think critically and try to find true passion – all of which takes time and cannot be done with no self-reflection. In fact, his credo should be replaced with "plucking the day", as it reflects his philosophy in a more adequate way. The forceful act of seizing is an overinterpretation of Keating’s teachings, as well as Horace’s poetry itself. Also, it is important to note that Horace’s poem is directed to a Greek woman named Leuconoe, who might be a slave. The lyrical subject uses the phrase Carpe diem in order to seduce her in a rather subtle way. The notion of “plucking” is supposed to convince Leuconoe to adapt a hedonistic attitude and stop thinking about the consequences of her actions. In this context Carpe diem can be seen as a simple rhetorical figure – the man might be trying to persuade Leuconoe to do something she is not supposed to. Perhaps this famous phrase originates from an empty pretense and its deeper meaning is a product of many reinterpretations, one of which is a theme of Dead Poets Society.

As Peter Weir, the director of the movie, said: "The story was so pregnant with metaphors, you didn’t have to try hard to unearth them. They just sprang to life" (Weir in Bloomenthal, 2019). Indeed, the story is filled with symbols and metaphors, one of which is the crown of branches worn by Neil during the play. When he comes back home to find out that he is going to a military academy, he still carries the crown in his hands, as a source of comfort or a totem, that reminds him who he truly is. Later, soon before he commits suicide, he takes of his shirt, puts on the crown and looks through an open window. There are many ways to interpret this scene, one of which is looking at Neil’s crown as a reference to Bacchus’s crown of vine leaves. In this sense, it signifies a state of ripeness approaching the decay, which can be seen as a harbinger of Neil’s death. Also, the crown may be interpreted as a reference to the biblical crown of thorns, a symbol of great suffering and sacrifice, which Neil is about to make. In a way he sacrifices his life in order not to betray himself as he has no other means of resisting his father’s will.

What is more, placing members of the Dead Poets Society in a cave seems to be an inversion of the famous Plato’s cave – an allegory of the effect of education and the lack of it on human nature. According to Plato, those who stay in the metaphorical cave can only see the shadows of the real world and therefore will never grasp the meaning of the most important values in human life. Only those who find the courage to go outside may be enlightened by wisdom and perceive the reality as it truly is. Weir’s concept seems to be an exact opposite – entering the cave is a first step towards finding true passion, beauty, courage and freedom of self-expression, whereas the world outside requires constant pretending and self-control. The policy of Welton Academy objectifies students and does not allow them to think critically or be individuals. By reviving the Dead Poets Society Neil, as well as other members, makes a step towards restoring his agency and regaining control over his life. Moreover, when the group of students is running through the woods towards the cave it seems like they are traveling to an alternative reality. They are dressed "in submariner jackets with hoods, as if they were like primitive monks, engaged in some sort of ancient rite of passage "(Weir in Bloomenthal, 2019). This “rite of passage” can be seen as a fundamental change in the way they perceive the world and their place in it. In this sense, the cave becomes a temple in which the members of the Dead Poets Society read poetry as a sacred text, in order to experience something truly moving and spectacular. The cave provides an escape from reality, but also allows them to find their own truth, which affects various spheres of their lives.

Further Reading

Bloomenthal, Andrew, “Dead Poets Society Retrospective with Tom Schulman, Peter Weir and Ethan Hawke”, Script, June 6, 2019 (accessed:September 14, 2022).

Carpe Diem merchandise for teenagers and young adults (accessed: September 14, 2022).

Horace, Ode 1.11 at ThePrinceSterling YouTube channel (accessed: September 14, 2022).

Luu, Chi, “How “Carpe Diem” Got Lost in Translation”, JSTOR Daily, August 7, 2019 (accessed: September 14, 2022).

Marsilio, Maria S., “Two notes on Horace, Odes 1, 11”, Quaderni Urbinati di Cultura Classica, New Series, 96.3 (2010): 117–123 (accessed: September 14, 2022).

Perdue, Leo G., “Sage, Scribers, and Seers in Israel and the Ancient Near East: An Introduction” in Leo G. Perdue, ed., Scribes, Sages, and Seers: The Sage in the Eastern Mediterranean World, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008, 57.

The 100 Greatest Movie Quotes of All Time by American Film Institute (accessed: September, 14, 2022).

The Republic of Plato, translated with notes and interpretive essay by Alan Bloom, New York: BasicBooks, 1991, 193.