Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

UK: Edward Frederic Benson, David Blaize, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1916, 316 pp.

US: Edward Frederic Benson, David Blaize, New York: George H. Doran Company, 1916, 365 pp.

ISBN

Available Onllne

The first edition (US) available at the Internet Archive (accessed: March 28, 2025).

The first edition (US) available at Project Gutenberg (accessed: March 28, 2025).

Genre

Bildungsromans (Coming-of-age fiction)

School story*

Target Audience

Children (boys)

Cover

Cover of the US edition from 1916. Retrieved from Internet Archive, public domain (accessed: March 28, 2025).

Author of the Entry:

Keelia McKone, University of New England, kmckone@myune.edu.au

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

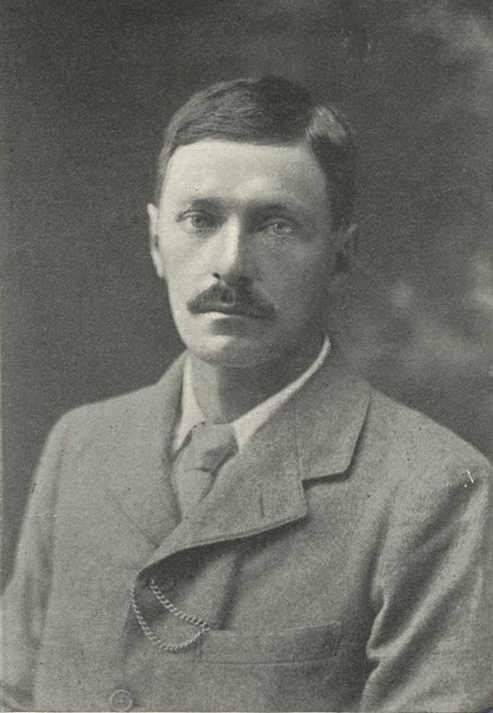

Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons, public domain (accessed: March 28, 2025).

Edward Frederic Benson

, 1867 - 1940

(Author)

E.F. Benson (known as Fred to his friends) was born in 1867 to Edward and Minnie Benson. One of six children, Fred was a prolific author of many genres, including social comedies, memoirs, school stories, and ghost and supernatural stories. Fred’s family were incredibly important in the late Victorian period; his father, Edward White Benson, was the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1883 until 1896, and his brothers, Arthur Christopher Benson and Robert Hugh Benson were also writers, with Arthur penning the lyrics for the Coronation Ode and “Land of Hope and Glory”, and Robert producing several religious works and being a Catholic convert, controversial for the son of the Archbishop of the Church of England. Their father suffered from “acute mental depression, which in early days had a blackness and fierceness of misery”, affecting the whole family, with Arthur and Maggie in particular suffering from severe depression throughout their lives (Arthur Benson, quoted in Goldhill 40–41). Fred’s two other siblings, Martin and Nellie, died young, and their loss was profoundly felt by the entire family, exacerbating their tendencies towards depression. Fred attended Marlborough public school in Wiltshire, where he had several romantic friendships with other boys. Today, the Benson family would be understood to comprise of queer people who didn’t conform to reproductive heteronormative standards of their day: after the death of her husband, Fred’s mother Minnie lived with her friend Lucy Tait in the same house as his sister Maggie and her female partner Nettie. Fred and his brothers also had relationships or attachments with other men. All members of the family have been called compulsive writers and all but Fred “inherited their father’s manic depression” (Carabine 8). Together they produced an usually large amount of writing (more than 200 books were published and thousands of pages of unpublished material). Further, both Fred and Arthur wrote multiple memoirs, painting a comprehensive picture of the family and their acquaintances. But each member of the family had psychological troubles, and as Goldhill comments:

“the self-distortion of depression and madness is a repeated, damaging vector in the rewriting of the family’s personal life. For the Benson family, there is a constant redrafting of the self, in conversation, in narrative, in writing – and in the eyes – the writing – of each other. This is a family that repeatedly and continually (re)wrote itself.” (Goldhill 8)

While at Cambridge University, Fred studied Classics (known then as “Greats”) and then went on to Greece in 1890–1891 to participate in archaeological excavations. During the Greco-Turkish War of 1897 and the surrounding years, Fred worked as a journalist for English language newspapers and travelled back to Greece many times throughout the late 1890s and early 1900s. His first novel, Dodo was published in 1893 to huge success, although there was some controversy surrounding the work, which angered his father’s “sense of seriousness” with Fred’s “flippant and disengaged” personality (Goldhill 6); the protagonist, Dodo, was deemed to be a roguish and “witty young woman in high society, beautiful, wilful, direct and utterly heartless” (Masters 99), and although the novel was a best seller with twelve editions in the first year of publication, Fred soon came under criticism for seemingly basing the main character on one Margot Tennant, daughter of a Glasgow industrialist family who was “vivacious, quirky, electric, with an embarrassing habit of saying whatever was in her mind” who Fred was “captivated” by (Masters 101–102). Although at the time of publication Dodo was very popular and “the talking-point of the moment”, Fred later wrote that the novel was “hideously crude [and] blatantly inefficient” (Masters 102; Benson, quoted in Masters 106). The influence of his interest in Classics and travels to Greece appear throughout his work, particularly in his novels set at school and comedies of manners, as well as his historical fiction, some of which was set in Greece during the conflicts with the Ottoman Empire and Turkish occupation. Fred’s written work spanned across decades and many genres, with his most popular today being his ghost stories and comedies of manners, particular the Mapp and Lucia series, which has been adapted into two television series (1985 for ITV and 2014 for the BBC).

Sources:

Carabine, Keith, “The Author’s Life” in E.F. Benson, The Complete Mapp & Lucia, Volume One, Ware: Wordsworth Editions, 2011, 7–10.

Goldhill, Simon, A Very Queer Family Indeed: Sex, Religion, and the Bensons in Victorian Britain, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Masters, Brian, The Life of E.F. Benson, London: Chatto & Windus, 1991.

Bio prepared by Keelia McKone, University of New England, kmckone@myune.edu.au

Translation

Swedish: David Blaize, Lund: C.W. K. Gleerup, 1923, 270 pp.

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

Benson, E. F., David Blaize and the Blue Door, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1918,

Benson, E. F., David Blaize of King’s, New York: George H. Doran Company, 1924.

Summary

David Blaize follows the titular David as he journeys through his preparatory school and public school before he graduates and attends Oxford University (explored in David Blaize of King’s, also titled David of King’s: Benson, E. F., David Blaize of King’s. George H. Doran Company, 1924). Throughout the novel, David has several friends, including Bags, Adams, and most importantly, Frank Maddox. Frank is David’s closest friend and the two have an intense bond that continues into their university life. Through David’s time at his two schools, he plays a lot of cricket, attends class, and attempts to avoid the embarrassments of his father, a clergyman, when he comes to visit. While the novel is a fairly typical public-school story and bildungsroman, it highlights an idealised view of late nineteenth century boys’ education, with a focus on sport, the beauty of nature, friendship, and the influence of classical (particularly Ancient Greek) mythology and culture on the childhoods of middle- and upper-class boys of the time. David Blaize was read widely during the First World War by men at the Front, reminding them of their simpler childhoods before the war.

Analysis

Throughout David’s education at Helmsworth Preparatory School and Marchester public school (as in real life for upper-class boys), study of the Classics is integral to the education system. Although David is not an excellent student, he has several revelations throughout the novel from his classical studies that affect his outlook on life and ultimately make him a more generous, understanding, and, in some ways, affectionate, boy. In particular, his study of Aristophanes culminates in the realisation that “they had all become people who went to the theatre like anybody else, and went to Olympia, just as anybody now might go to the Oval, and had play-writers like Aristophanes who made just the same sort of jokes as people make nowadays” (Benson 255). The ancient Greeks are hugely influential for both David and his friend Frank, who study Plato and Sophocles together. Chris Mounsey argues that through their study of Plato’s Symposium, David and Frank’s relationship becomes an inverted form of the eromenos and erastes, which is then reciprocated between David and his fag/younger student assistant Jevons when he is in the sixth form (Mounsey 73–74). This relationship structure was upheld throughout queer, neo-classical, and decadent circles in the late-nineteenth century, particularly among groups of upper-class men connected with public thought about male homosexuality, including J.A. Symonds, Walter Pater, and Oscar Wilde.

David’s relationship with his friends, particularly the older Frank Maddox, is integral to his maturation as a student and a man, and is almost unabashedly queer in its representation. In preparatory school, David “adores” the “godlike” Hughes (Benson 35), and when he arrives at Marchester he quickly becomes enamoured with Frank, who represents David’s ideal of boyhood. The “hero-worship” that David experiences in regards to Frank makes “his heart burn… [when] the demigod had thrown a careless word to him” and David is in awe that “Maddox, the handsomest fellow in the world, the best bat probably that Marchester had ever produced, and altogether the most glorious of created beings” had even “noticed him at all” (Benson 183). David’s likening of Frank to a demigod highlights the prevalence of classical mythology in the childhood experiences and education of public boys’ schools, and also subtextually underlines the queer connotations of David’s admiration for Frank. In a particularly fruitful scene, Frank helps David construe lines of Sophocles’ Oedipus at Kolonos, where David realises how “ripping” the play is but is embarrassed that he likes it so much, “despite his barbarian instinct that things like the beauties of Greek literature might perhaps be thought about, but hardly talked of” (Benson 249). This embarrassment of appearing passionate about a topic is aligned with typical Victorian ideals of masculinity and the stoic “stiff upper-lip” mindset of the time. Throughout the late 1800s, interest in and reference to Ancient Greek had also become coded language for (male) homosexuality, and so this shame that David experiences about his interest in Antiquity can be understood as shame about his burgeoning understanding of sexuality. Through the study of Plato’s Symposium, ideas of spiritual love between men gained popularity, creating the subculture of Uranian writers and poets, who wrote about their passion for other men. Although David does not seem to share the passion for writing that Frank does, it is easy to imagine that Frank in the future would have enjoyed the writing of the Uranians and may have even written some of his own.

Though David has tendencies of becoming the fairly weak-minded and sport-focused “everyman”, it is through his relationship with Frank that he educates himself and becomes a softer, more emotionally mature and passionate man and student by the time the novel concludes.

Further Reading

Benson, E. F., David Blaize, The Hogarth Press, 1989.

Carabine, Keith. ‘The Author’s Life’ in E.F. Benson, The Complete Mapp & Lucia, Volume One, Wordsworth Editions, 2011, 7–10.

Dowling, Linda, Hellenism and Homosexuality in Victorian Oxford, Cornell University Press, 1994.

Ewie, ‘Reviews of the Works of Edward Frederic Benson (1867–1940)’, E.F. Benson – The Complete Works, (accessed: October 23, 2024).

Farinou-Malamatari, Georgia, "Philhellenism and after: Greece in E. F. Benson’s Life and Work", Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 47. 2 (2023): 218–236.

Goldhill, Simon, A Very Queer Family Indeed: Sex, Religion, and the Bensons in Victorian Britain, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Masters, Brian, The Life of E. F. Benson, Pimlico, 1993.

Mounsey, Chris, Being the Body of Christ: Towards a Twenty-First Century Homosexual Theology for the Anglican Church, Routledge, 2014.

Naylor, Carol, "Passion and Power: Edwardian Censorship and E.F. Benson’s Homoerotic Public School Novel David Blaize (1917)", Papers: Explorations into Children’s Literature 11. 2 (2001): 17–26.