Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Μαρίζα Ντεκάστρο [Marisa De Castro], Στο μουσείο [Sto mouseío] (First Readers [Πετάει – Πετάει (Petáei – Petáei)]), ill. Myrto Delivoria. Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2007, 39 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Instructional and educational works

Picture books

Target Audience

Children (target reader: 5+)

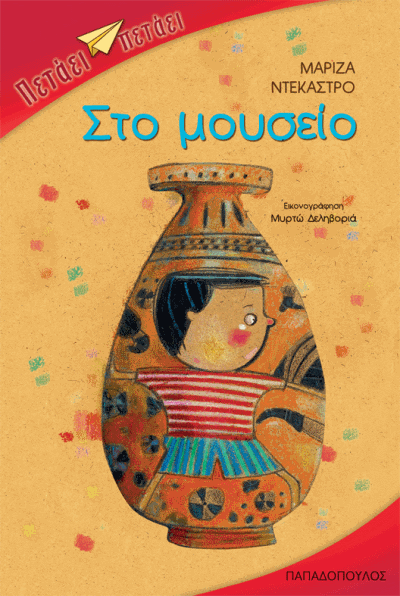

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher. Retrieved from epbooks.gr (accessed: July 5, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Marisa De Castro

, b. 1953

(Author)

Marisa De Castro was born in Athens and was educated at the Sorbonne, Paris. De Castro, who has worked as a primary-school teacher, has written a large number of children’s books, mostly about art history and archaeology.

Sources:

Profile at the epbooks.gr (accessed: July 3, 2018).

Profile at the metaixmio.gr (accessed: July 3, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Myrto Delivoria

, b. 1974

(Illustrator)

Myrto Delivoria is an award-winning professional illustrator of children’s books.

Source:

Profile at the epbooks.gr (accessed: June 3, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Translation

English: At the Museum, trans. Daphne Bonanos, Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2009, 40 pp.

Summary

The purpose of this book is to introduce young children to a museum environment. The book starts with a drawing of a museum, recognisable as the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, which is compared, and with good reason, to a treasure house. In the book’s opening pages, we form an impression that a museum is as much about a massive building (with gigantic stairs and big glass doors) as about antiquities (statues and vases) and a plethora of vibrant visitors of different ethnic backgrounds and age groups.

There is a sense of community among museum visitors, as teachers and high-school children, older than the readers of this picture book, wait to enter the museum. The community’s sentiments, possibly of apprehension for their journey of discovery and exploration once inside the museum, culminate with the phrase “Everyone loves the museum!”. This communicates a message about a shared experience for all museum visitors.

Having predisposed the reader positively, De Castro embarks, from page 12 onwards, on a presentation of key antiquities from Greek and foreign museums. We see, for example, ‘The Charioteer’ (Ηνίοχος in Greek) from the Archaeological Museum of Delphi, ‘Hermes of Praxiteles’ from the Archaeological Museum of Olympia, and a magnificently-painted black-figured cup by Exekias from the Staatliche Antikensammlungen in Munich. The latter, which shows Dionysos’ mythical journey in a sea of dolphin-pirates, is, arguably, the most-discussed Greek vase in scholarship*. De Castro does not name these well-known pieces of ancient art.

A boy in stripy clothes, whom we first saw on the Corinthian alabastron in the book’s front cover, narrates the story of viewing iconic images from antiquity. He comments on the relative size of different statues. There appears to be a fleeting reference to mythology, as the boy compares the huge marble statues to “giants in fairy tales”. More importantly perhaps, and according to the author’s focus on people-object interactions, the boy talks to the statues as if they were his friends. The boy admits that there can be no running and playing, no touching, and no loud talking. Here, De Castro provides instructions for appropriate behaviour in a museum, welcomed by teachers and others who lead young children to museums.

When the boy enters “a big room full of pottery”, he comments on the material (clay), shape, size, affordances for holding liquids, and decoration. We read about diverse gold, bronze, and iron artefacts, and we see a wreath and a helmet, which potentially allude to kings and warriors in children’s literature.

The book’s narrative closes with a museum guard asking the young boy whether he enjoyed the museum visit, and the boy answers in the affirmative and promises to come back “to explore the past” further.

The final section is entitled “Play and learn”. Some activities take the form of questions and answers. Children are encouraged to talk to the statue called ‘The little Refugee’ and fill in details about its age, material, and dress. The statue was brought to Athens by Greek refugees from Asia Minor in 1922**. Other activities involve drawing and putting together fragments of three vases.

* Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich, Inventory Number: 8729 (2044). See, for example, Fellmann, 2004: 13–19, pl. 2.1–2. Fellmann, Bernhard. CVA Germany 77, Munich 13. Attisch-schwarzfigurige Augenschalen (Munich: Beck, 2004).

** National Archaeological Museum, Athens, InventoryNumber: 3485 (accessed: July 6, 2022).

Analysis

The author and illustrator reproduce the experience of open and crowded spaces inside and outside highly-frequented museums, providing context for the consumption of “ancient works of art.” The book offers a story about people-object interactions and not a catalogue of museum artefacts. An experiential approach to children’s learning in Greek museums is much praised in contemporary scholarship*. De Castro’s commendable attention to the materiality of ancient art pieces is in tune with recent theoretical approaches in social anthropology**. The author prompts children’s curiosity about archaeological practice, including excavation and photography of valuable finds, which are called, unsurprisingly, “treasures”.

The illustrations by Myrto Delivoria are fun and have a multi-ethnic flair. A young boy in a striped T-shirt and shorts on the front cover, perhaps reminiscent of football-playing and summer holidays, adorns a Corinthian Archaic alabastron. He replaces the animals and monsters that customarily take centre stage in the decoration of such alabastra***. Delivoria does a superb job in illustrating artefacts such as pottery that date to different periods. Neolithic, Geometric, Archaic, and Classical ceramic wares are all shown. The visual narrative for young readers is varied. The depiction of puzzle pieces is a particularly inventive way to guide children through archaeologists’ and curators’ restoration and conservation of “wonderful things” in a museum. ‘The little Refugee’ shows a young hooded boy holding a dog. The pet looks more like a teddy bear in the illustration. The image is appealing for two key reasons. Firstly, children can easily identify with the “sweet aesthetics” of Hellenistic art****. Secondly, the image is topical in 2017 — some eight years after this book appeared in print — because of the refugee crisis. Thousands of children, mostly from war-stricken middle-eastern lands, cross the rough seas of the Aegean to find refuge in Greece before continuing their journey to northern Europe.

The English (by translator Daphne Bonanos) is easy to follow and includes popular phrases such as “wow!” and “It’s great fun!”

* See, for example, Kalogianni, Aimilia and Argyroula Doulgeri-Intzesiloglou, “Παιχνίδια στο Μουσείο. Εκπαιδευτικά προγράμματα της ΙΓ ΕΠΚΑ κατά τη διετία 2006 2008”, Το Αρχαιολογικό Έργο στην Θεσσαλία και Στερεά Ελλάδα 3 (2009): 531–539.

** See, for example, Miller, Daniel, ed., Materiality, London: Duke University Press, 2005.

*** For Corinthian alabastra, see, for example, getty.edu (accessed: August 3, 2018).

**** See Zanker and Graham, Modes of viewing in Hellenistic poetry and art, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004.

Further Reading

Information about the book at epbooks.gr, published 30 June 2009 (accessed: August 3, 2018).

Addenda

The book first appeared in Greek in 2007. At present, the Greek version appears to be out of stock. Not translated in additional languages.