Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

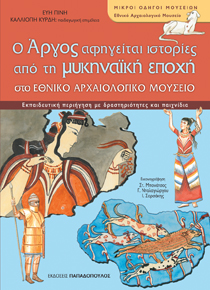

Evi Pini & Kalliopi Kyrdi, Ο Άργος αφηγείται ιστορίες από τη μυκηναϊκή εποχή στο Εθνικό Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο [O Árgos afīgeítai istoríes apó tī mykīnaïkī epochī sto Ethnikó Archaiologikó Mouseío], Short Museum Guides [Μικροί Οδηγοί Μουσείων (Mikroí Odīgoí Mouseíon)] (Series). Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2008, 32 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Illustrated works

Instructional and educational works

Target Audience

Children (target reader: 6+)

Cover

Courtesy of the Pubilsher. Retrieved from epbooks.gr (accessed: July 5, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Dorota Mackenzie, University of Warsaw, dorota.mackenzie@gmail.com

Kalliope Kyrdi (Author)

Kalliope Kyrdi studied Law and Pedagogy at the University of Athens, and has worked in primary school education. Kyrdi has been responsible for cultural matters in the 1st Directorate of Primary Education, Athens, since 2007.

Source:

Profile at the epbooks.gr (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Evi Pini (Author)

Athens-born Evi Pini studied Archaeology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Pini has been working for the Greek Ministry of Culture since 1990, specialising in children’s educational programmes.

Sources:

Information about the Author, see here (accessed: June 26, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Summary

The book is a guide to the Mycenaean antiquities in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. The first page offers background information about a museum visit for parents and teachers.

From page 4 onwards, the guide to the Mycenaean past begins with defining the temporal and geographical context. Readers are presented with a general narrative about the Achaeans arriving in mainland Greece. At first, the Achaeans practiced agriculture and animal husbandry, before becoming richer through trade in about 1600 BC (p. 5).

A reference to the word “myth” appears on page 8. Until the 19th century, people thought that the Homeric account of mighty Mycenaean kingdoms was all a myth. Heinrich Schliemann, however, discovered the rich tombs at Mycenae, proving that the Mycenaean world existed in time and space.

From page 9 onwards, we read about Mycenaean museum exhibits. Argos, a dog who lives in the Mycenaean gallery, greets the children.

Children are prompted to observe the details of Agamemnon’s mask, of swords, and of other luxury items (pp. 11–14), and think about function and materials, rather than art. Multiple interpretations are encouraged. A fresco showing a Mycenaean lady could be a depiction of a rich woman or a goddess (p. 15). Subsequent pages cover frescoes, writing, defence, and music, and present iconic images of the Mycenaean past, such as a helmet from boars’ tusks (pp. 18–21). Children learn about elite individuals.

Some activities at the end of the book, however, bring Mycenaean material culture closer to daily life (ancient and modern. On page 23, we have comics-inspired dialogues between real people, that is, traders. Other interactive activities include the study of Mycenaean decorative designs, of writing, of the acropolis at Mycenae, of a route from Pylos to Mycenae, and of sword hunt scene (pages 24-30). The book closes with answers to questions, with a bibliography, and with detailed captions for all illustrations.

Analysis

This book about the Mycenaean past makes some reference to Homeric myths and traditions.

Contextual information reminds us of history textbooks, even though we are in prehistoric times. We have a list of key Mycenaean dates, ranging from the tombs at Mycenae (1580–1550 BC) to the end of the Mycenaean kingdoms (1100 BC). Interestingly, the illustrators show these dates on a slab that resembles an inscription from later times, perhaps Classical or Hellenistic.

The narrative is interspersed with standard keywords, such as “civilisation”, which could appeal to adult readers by reminding them of traditional schoolbooks in their childhood. The (historical?) overview continues with a focus on economic matters that guaranteed prosperity: seafaring; trade; and craftsmanship. Inevitably, a decline followed from the late 13th century BCE onwards, after the Trojan War (p. 7). The underlying idea is that civilizations rise and fall.

Objective knowledge, as exemplified by Schliemann’s and his followers’ excavations, is juxtaposed with the possibility of fantasy in textual accounts. The term “myth” is equated with what does not hold true, by contrast to archaeological and historical facts.

The authors provide background information for key terms and ancient figures, such as “acropolis” (p. 6) and “Pausanias” (p. 8). Yet, some ancient figures, like “Cassandra”, Priam’s daughter (page 8), are mythological, and this is not quite fully acknowledged. To appreciate Cassandra’s mythological status, readers need to combine what they read about her on page 8 with information on page 7, where it is explained that ancient people preserved memories of the Mycenaean world in myths that were passed from generation to generation.

Information in a box enlightens us that Argos was Odysseus’ faithful dog, and that Odysseus was a mythical king. Argos’ mythological connection is made explicit here, blending the real with the imaginary in children’s minds. And yet, another piece of information, appearing in a separate box just below that about Odysseus’ dog, is about the word “argos”, which means shiny in ancient Greek. Once again, there appears to be an emphasis on objective knowledge. We are not reminded of Argos’ Homeric role when we notice the dog’s presence in pages 9 to 22. Rather, the dog appears to exist as a real entity, helping children to focus their attention. On page 18, in particular, Argos tells children that a white dog in a fresco from Tiryns is a drawing of himself. Argos’ homeland, Ithaki, has been forgotten here. Also, Argos reminds readers of talking animals in children’s literature and of real pet animals that frequent public buildings.

The authors encourage children to think imaginatively. Each museum exhibit, we are told, bears a secret message in a secret language about the past (page 10). Whether the authors refer to object biographies remains unclear. In the section with interactive activities, some traders hold a dagger and a helmet (p. 23), like those in the museum. Here we can visualise object biographies, and how people other than elites handled remarkable pieces of craftsmanship.

Representations of ancient artefacts are very close to the originals. The colours are bold, and with good reason. Children could contrast, for example, the bold blues in the book with the faded and cracked surfaces of fresco fragments in the museum. Text appears in various colours, such as black, blue, red, and green on page 25. Any reader is drawn into the book, compelled to flick through and enjoy the art of text and image.

Teamwork is encouraged throughout the book. On the inside cover, students are asked to fill in their name and whom they visited the museum with. It is commendable that a museum visit is understood as a shared experience, since children are made to think creatively about the exhibits and communicate their thoughts and ideas with others.

Further Reading

Information about the book at epbooks.gr, published September 5, 2008 (accessed: July 27, 2018)

Addenda

The book forms part of a series of 6 Short Museum Guides that appeared in print from 2008 to 2010.