Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Details

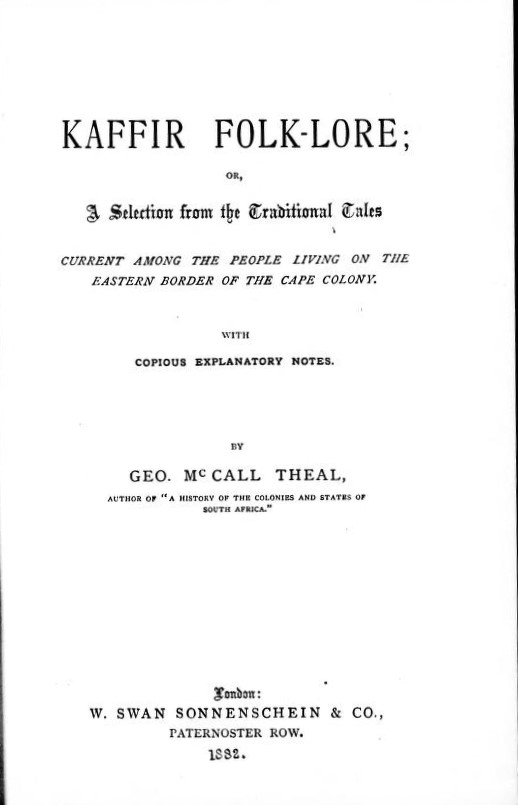

Theal, George McCall, “The Story of Five Heads” in Kaffir Folk-Lore; or, A Selection from the Traditional Tales Current among the People Living on the Eastern Border of the Cape Colony, with Copious Explanatory Notes, London: W. Swan Sonnenschein & Co., [1882], 47–54.

ISBN

Available Onllne

First edition, 1882 (accessed: April 11, 2022).

Second edition, 1886 (accessed: April 11, 2022).

Genre

Folk tales

Target Audience

Crossover

Cover

Cover retrieved from Internet Archive (accessed: April 11, 2022). Public domain.

Author of the Entry:

Eleanor A. Dasi, University of Yaoundé 1, wandasi5@yahoo.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaounde 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Retrieved from Wikipedia. Public domain (accessed: April 11, 2022).

George McCall Theal

, 1837 - 1919

(Author)

George McCall Theal was born in the United States of America. He moved to Sierra Leone before and then to South Africa, where he became a teacher, journalist, miner and genealogist, archivist and historian. He had a keen interest in South Africa’s origin, people and cosmological realities. Throughout his life in South Africa, he published articles and books on the Bantu and Xhosa stories, folklore and mythology. Among his numerous publications are Compendium of South African History and Geography (1873), History of South Africa (1873), Kaffir (Xhosa) Folk-Lore (1882), and a catalogue of books and pamphlets relating to Africa South of the Zambesi (1912), and South Africa–Story of the Nations Series (1917).

Source:

Saunders, Christopher, "George McCall Theal and Lovedale", History in Africa 8 (1981): 155–164.

Bio prepared by Eleanor A. Dasi, University of Yaoundé 1, wandasi5@yahoo.com

Summary

There once lived a man who was blessed with two daughters. The eldest was called Mpunzikazi, while the youngest was Mpunzanyana. Both had attained marriageable ages. One day, he travelled to another village and was told the chief of the land was looking for a wife. He took it as an opportunity for his daughter and when he arrived home later that evening, he summoned both girls and broke the good news to them. Without any hesitation the eldest opted to become the unknown chief’s wife, in the unknown land. Her father decided to organize a bridal train that would accompany Mpunzikazi to her supposed husband’s home, in such a way that the news of her getting married would spread like wild fire. But all of the father’s efforts were futile as the girl insisted on going alone.

She finally set out for the journey. On her way, she met a mouse and a frog who opted to show her the right path to follow but out of pride and arrogance, she turned down their offer and continued her journey. After a while, she felt tired and hungry and then decided to have her lunch under a tree. A herdsman, who was dying of hunger approached her and asked if she could give him some of her food to eat. She did not only refuse but also arrogantly asked him to leave her sight. After she had eaten and rested, she continued her journey. She met an old woman who gave her the following piece of advice: “You will meet with trees that will laugh at you: you must not laugh in return. You will see a bag of thick milk: you must not eat of it. You will meet a man whose head is under his arm: you must not take water from him" (p. 49). And as usual, she did not heed to the advice. Rather, she reprimanded the old woman for daring to advise her. She went ahead and did all what she was advised by the old woman not to do. When she finally reached the village river, she met a young girl who had come to fetch water. This girl happened to be the chief’s younger sister, her supposed sister-in-law to be. She, too, vainly struggled to give Mpunzikazi advice. But again she never paid any attention to her. The bride-to-be finally reached the village of her future husband. Without any waste of time, the inhabitants asked her where she came from and what her mission in the land was. In a very angry tone, "I have come to be the wife of the chief" (p. 50), she said. And the people were shocked to see a bride without a bridal train. However, she was told the chief was not at home. But nevertheless, they received her and asked her to prove her worth by preparing a meal for her husband before his return. The arrival of the chief was not unannounced, as she heard a very violent wind and in the end she saw him ‘Mr. Right’, who was nothing but a mighty snake with five heads. She felt so terrified and started trembling. After settling down, the to-be husband ordered Mpunzikazi to serve his food. She hurriedly did as she was told. After tasting the food, the snake husband told her that there is no way she can be his wife, and then sent her to the world beyond by striking her with his tail.

After some time, her sister, Mpunzanyana, decided to replace her sister as the chief’s new wife. She set for the trip with her companions and as they went, she equally met the same friends of good will whose advice her stubborn late sister had rejected. When she finally arrived at her promised land, she was given a warm reception and was later asked to prepare food to await the chief who was absent at the time she arrived. In the same manner as with her late sister, the chief made his entry. Contrary to her sister, Mpunzinyana proved to be very brave when she saw the gigantic snake with five heads and was told he was the husband she had come to marry. She served him food with no fear. After eating the food, Makanda Mahlanu (snake man) said to her “you shall be my wife” (p. 53). He further presented her with plenty of ornaments, transformed into a man, and she became his favourite wife.

Analysis

The story of five heads, on the one hand, seems to confirm the general saying that pride goes before a fall. Because of her pride, arrogance, disrespect for her father, her people and her tradition, Mpunzikazi misses the opportunity to get married and even loses her life. On the other hand, the story suggests, through Mpunzanyana, that humility, respect and modesty are key to a successful life. Unlike her sister, she is endowed with wisdom as she listens to and puts in practice all the advice she received on her way to the foreign land. Her meekness and humility guarantee for her a smooth journey. She proves herself worthy as a wife-to-be of a chief*. The traits she manifests are virtues that are upheld and recommended in many cultures and religions from ancient to present.

In addition, the story explores the African belief that the gods disguise into any form to warn or guide humans against any impending doom. From the mouse and the frog through the hungry herdsman and the laughing trees to the bag of milk and the man with his head under his arm, these were all warnings of the evil that lies ahead if the instructions were not obeyed. Mpunzikazi spites these warnings and meets her doom while Mpunzanyana heeded all the advice and had a successful end.

The story also hints at the way marriages are conducted amongst the Kaffirs of South Africa and in some other parts of black Africa. Usually, suitors are arranged for girls by their fathers, who feel proud when their daughters get married. That is why the father in the above story wishes for Mpunzikazi to have a bridal train that would spread the news of her marriage. However, the girls’ opinions are not sought, even when they are expected to be fourth, fifth or even sixth wives. But again, sometimes because the girls are desperate for marriage, since unmarried women are not respected in most African societies, they accept the first opportunity that presents itself. The two sisters in the story accept to be the wife of the chief without having seen or met him. Most often, the women are not fulfilled in such marriages except in cases where they become the favourite wife like Mpunzanyana.

* In African traditions, wives of chiefs are expected to have exemplary behaviour as to attract respect and honour from the subjects.

Further Reading

Cairns, D., "Hybris, Dishonour, and Thinking Big", Journal of Hellenic Studies 116 (1996): 1–32.

Theal, George McCall, “Notes. The Story of Five Heads” in Kaffir Folk-Lore, London: W. Swan Sonnenschein & Co., [1882],197–200 (accessed: April 11, 2022).

Zenani, Nongenile, The World and the Word: Tales and Observations from the Xhosa Oral Tradition, collected and edited by Harold Scheub, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992.

Addenda

The word kaffir or kafir is a derogatory word that is translated to English as disbeliever and infidel. By the 15th century, the word was used to refer to non-Muslim African natives who were captured and sold to Asian and European merchants. The captives were called kaffirs. In South Africa, kaffir is a racial term. (Baderoon, Gabeba. "The Provenance of the Term ‘Kafir’ in South Africa and the Notion of Beginning." (2012)), available here, (accessed: April 22, 2020).

Origin/cultural background:

The Xhosa, also written as isiXhosa, made of subgroups like Mpondo, Mpondomise, Xesibe, Thembu, Bhaca, Bomvana, and Mfengu, are the eastern South Africans and at the same moment, it is a Nguni Bantu language of South Africa and Zimbabwe. According to the oral tradition of the people, their creator deity is Xhosa, also called uQamata or uThixo. He is honored through rituals. The Xhosa rite of passage start from birth with the umbilical cords of babies which are burned to protect them from evil spirits. Also, children are circumcised when they are to be initiated into adulthood. The initiation processes are marked by the sacrifice of a goat. Like most African ethnic groups, the Xhosa believe in ancestors and spirits.

Read more everyculture.com (accessed: April 22, 2020).

Although these myths were collected so many years ago, they are still being told to children and young adults in traditional African communities. And like all other oral narratives, several versions of the same story may be available in different places.