Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Ray Ching, Aesop’s Kiwi Fables. Auckland: David Bateman Ltd, 2012, 227 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Fables

Illustrated works

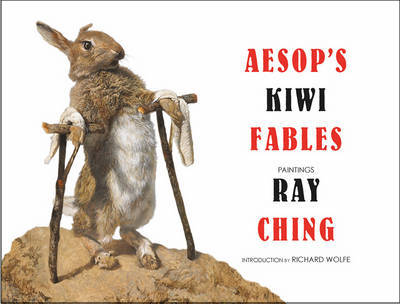

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher. Retrieved from batemanbooks.co.nz (accessed: 5 July 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Margaret Bromley, University of New England, mbromle5@une.edu.au

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaounde 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

Ray Ching

, b. 1939

(Author, Illustrator)

Ray Ching, otherwise known as Ray Harris-Ching, was born in 1939 in New Zealand, descended from English migrants from Cornwall, who, in 1840 were some of New Zealand’s first permanent coloniser settlers in Nelson. Brought up on the family farm a hundred years later, Ching became familiar with the native fauna and flora.

A school visit to the local museum, particularly a collection of taxidermied hummingbirds, inspired Ching’s interest in birds. At the age of twelve he dropped out of school to take up an apprenticeship in advertising. After working in the fields of graphic design, architecture and illustration Ching began his career as an artist by drawing taxidermied birds borrowed from the Dominion Museum in Wellington. His internationally award winning oil paintings of birds and wildlife are often based on this easily accessible resource. At his first exhibition, Thirty Birds, in Auckland in 1968 he was discovered by Sir William Collins, renowned publisher and keen ornithologist, who introduced him to British naturalist Sir Peter Scott, which launched his international career.

Ching’s works are characterised by realism, drama and excitement, qualities which, early in his career, earned him the prestigious commission in 1969 to illustrate the Reader’s Digest Book of British Birds, a publication which continues to be the best selling ornithological reference in the United Kingdom. After moving to the United Kingdom in 1968 Ching pursued a career in various artistic media, including sculpture, painting and photography. Ching exhibits regularly in New Zealand and around the world. He is considered to be one of the best wildlife painters of the twentieth century.

Many of Ching’s paintings are published in books:

- Ching, Ray. Dawn Chorus: The Legendary Voyage to New Zealand of Aesop, the Fabled Teller of Fables. Auckland: Bateman, 2014.

- King, Michael. The Penguin History of New Zealand. Auckland: Rosedale, 2003.

- Fuller, Errol and Lance, David. Voice from the Wilderness, Ray Harris-Ching. Shrewsbury: Swan Hill Press, 1994.

- Sinclair-Smith, Carol. Ray Harris-Ching, Journey of an Artistt. South Carolina: Briar Patch Press, 1990.

- Images copyright Ray Ching. Represented by Artis Gallery, Parnell, Auckland (accessed: June 4, 2018).

Bio prepared by Margaret Bromley, University of New England, mbromle5@une.edu.au

Summary

These are Aesop’s Fables adapted, illustrated and set in New Zealand, substituting native fauna for Aesopian characters. There are forty seven fables in Ching’s Aesop’s Kiwi Fables.

The Cat & The Cockerel upon a Journey; The Blackbird & His Tail; The Kiwi at the River; The Huhu Beetle & His Shadow; The Kiwi & The Goose; The Old Tuatara & the Possum; The Cat & the Kiwi Chick; The Kiwi & the Jewel; The Thoughtful Kea; Huia & Kokako of Old; The Old Man & Death; The Takahe &the Pukeko; The Judgement of the Council; The Cat, the Duck & the Kiwi; The Horse & the Stag; The Morepork & the Frog; Pelorus Jack & the Monkey; Tarapunga &the Gulls; The Little Fish & the Penguin; The Travellers & the Wattle; The Leaves in the Wind; The Boastful Traveller; The Cow & the Fly; The Crab in the Paddock; The Student & Her Flowers; The Barrel of Good Things; The Gardener & the Peacock; The Beauty Contest of the Birds; The Birds & the Cuckoo; A Cat & a Cockerel; The Rabbit & His Friends; The Sun & the Southerly Wind; The Rivers & the Sea; Kereru, Tiu & the Sparrow; The Dancing Duck; The City Hedgehog & the Country Hedgehog; The Weka & the Pheasants; The Skylark & Her Young; The Huia with One Eye; Reischek &the Satyr; Kokotu & the Blackbird; The Traveller and Truth; The Hawk, The Falcon & the Pigeons; Walter Buller & the Singing Tui; The Macrocarpa & the Magpie; The Sealer & the Unicorn; The Two Pots.

Set in New Zealand, the last habitable landmass on earth, which lacked any land mammals as predators to its diverse bird population, including many flightless species, Ching’s fables depict the desecration of local native fauna and environment by imported species.

Around 800 years ago, Maoris arrived and hunted some birds to extinction, including the giant moa. Subsequently, British colonisers played a pivotal role in the demise of native birds, by their destruction of native species, but particularly through the introduction of foreign species that decimated the local fauna. Ching’s preoccupation is the enduring role of European settler colonisers on the environment.

Whereas the Fox and Wolf dominate in many versions of Aesop’s fables, Ching’s favourite character is the Kiwi, a nocturnal and flightless bird that is rapidly becoming endangered. The villains in Ching’s fables are often the introduced species that colonise the environment and kill off native species. However, this anthology of fables sets up examples of human attitudes and behaviour that subliminally questions humans’ long term attitudes towards nature and the environment.

Aesop’s most familiar fable of The Hare and the Tortoise is rewritten as The Old Tuatara and the Possum. The slow moving Tuatara, with its “ancient lineage”, is the single surviving species of lizards which flourished 200 million years ago in the age of the dinosaurs. Now protected in sanctuaries, in the wild they continue to be threatened by the loss of their habitat and introduced predators.

In Ching’s fable, the Tuatara’s contestant is the speedy Possum. Introduced from Australia to New Zealand in 1837 to establish a fur industry, possums have become a major pest that presents a major threat to New Zealand’s ecology, habitat and wildlife. Most New Zealanders would immediately appreciate the symbolic substitution of these native and imported species in the fables. But for some Maori iwi (tribal groups) there might be coded knowledge and meaning. Tuatara are regarded as the messengers of Whiro, the god of death and disaster. They also indicate tapu, the borders of what is sacred and restricted.

Cats in particular are depicted as duplicitous and manipulative, persistent predators of native fauna, which is undisguised by their anthropomorphisation through the use of traditional old fashioned props. The feral looking Cat in The Cat and the Kiwi Chick “dressed himself to look the part of a doctor” is wearing glasses and walking on his hind legs, “carrying a suitably impressive set of medical instruments in a Gladstone bag”. He is after a meal of an ailing Kiwi chick, but the protective parent is undeceived, the moral being “A villain may disguise himself but he will not deceive the wise.”

Ching’s version of Aesop’s The Peasant and the Satyr reverses the traditional role of host and visitor. In Resichek and the Satyr Ching depicts a real historical person, “Reischek, the taxidermist, … collecting specimens for the nation’s museums”, who invites the Satyr to stay with him. “Walter Buller and the Singing Tui” refers to another gentleman ornithologist, not a professional scientist, who participated in endangering species through his collections for the British Museum.

Ching sees his homeland New Zealand as land like “nowhere else on earth;” one in which fragile and unique native species are threatened to extinction. His substitution of the traditional Aesopian characters, in their European pastoral setting, with New Zealand native fauna, in specific New Zealand environments is both entertaining and instructional. Ching’s intention is the development of long term attitudes towards nature and the environment in his readers who are offered complex understandings through familiar and simple texts and layered meanings in the illustration.

Analysis

The introduction to the anthology, written by freelance writer and curator Richard Wolfe, situates Ching’s fables in the history of Aesop’s Fables, including their oral and publication histories. Beginning with “Aesop, a Greek slave with uncertain origins - if in fact, he existed at all” (p. 12) accredited with developing the genre of the fable, Wolfe informs us that “His talent for telling fables won him his freedom, but it could not overturn an accusation of theft and his subsequent execution by being hurled over a cliff” (p. 13). Thus the reception of fable as a subversive form of literature underpins this anthology.

Richard Wolfe’s introduction to Ching’s Aesop’s Kiwi Fables, offers an excellent overview of the oral and publishing history of Aesop’s fables, including a range of woodcuts from European publications from the fifteenth to early twentieth centuries. The evolution of new processes for the reproduction of illustration allowed a greater diversity of artistic interpretation. Wolfe situates Ching’s fables in the history of theses adaptations. The layout and high-quality production distinguishes this book as a work that appeals to an adult and child readership.

Ching uses taxidermied animals and birds to create his dramatic, lifelike oil paintings, which he borrows from museums and private collections such as the Te Papa Museum (formerly the Dominion Museum) in Wellington. Ching, however, claims that he is not a collector of taxidermied animals and birds.

As well as referencing his own homes, in New Zealand and the UK, Ching manipulates local New Zealand history and often sets his stories in specific places that are named: for example Manawatu, Fiordland, and the Desert Road plateau. The first fable shows the Cat and the Cockerel setting out on their journey across New Zealand from Ching’s own house at Bradford-on-Avon UK; whereas the second fable situates events from a modest weatherboard cottage that is typical of rural New Zealand, similar to that in which Ching himself grew up.

This anthology of Aesop’s fables offers an interactive reading experience in which illustrations present extended readings of the written text. Ching’s lavish realistic images entice readers to appreciate close up views of the animals and birds depicted. The specific geographical context of the ecologically fragile fauna and flora is intriguing and accessible to a range of readers, from young children who have local understandings of these animals and their habitat to young adult readers and adults who can appreciate them as a postcolonial examination of human attitudes towards environmental sustainability.

Though some of these fables fall outside the capabilities of younger readers, clearly the content invites more sophisticated readings and cumulative understandings of meaning and context. They demonstrate the ongoing adaptability of the ancient heritage of Aesop’s cautionary tales to a new environment and social context.

Further Reading

Ching, Ray, Dawn Chorus: The Legendary Voyage to New Zealand of Aesop, the Fabled Teller of Fables, Auckland: Bateman, 2014.