Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

John Maxwell Coetzee, Diary of a Bad Year. Melbourne: Text Publishing Company, 2007, 178 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Historical fiction

Novels

Target Audience

Crossover

Cover

We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover.

Author of the Entry:

Divine Che Neba, University of Yaoundé 1, nebankiwang@yahoo.com

Didymus Duanla Tsangue, University of Yaoundé 1, diddytsangue@yahoo.ca

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaounde 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

Eleanor Anneh Dasi, University of Yaounde 1, wandasi5@yahoo.com

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

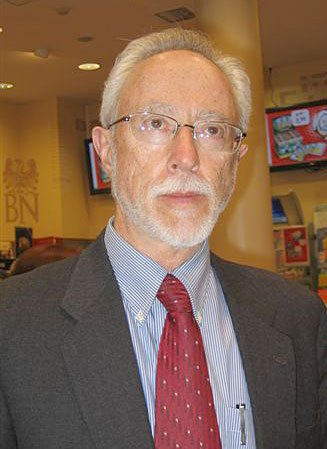

J.M. Coetzee in Warsaw, 2006. Photograph by Mariusz Kubik, GNU Free Documentation License Version 1.2 Source: Britannica (accessed: October 18, 2021)

John Maxwell Coetzee

, b. 1940

(Author)

John Maxwell Coetzee was born of Afrikaner parents on February 9, 1940 in Cape Town, South Africa. He attended St. Joseph’s College, a Catholic School in Cape Town, where he received his Bachelor of Arts with honors in English and Mathematics at the Universality of Cape Town in 1960 and 1961 respectively. He relocated to the United Kingdom where he was adjunct lecturer, and later enrolled on the Fulbright program in the University of Texas. He was arrested in 1970 for protest against the war in Vietnam and later returned to South Africa to teach Literatures in English at the University of Cape Town, where he was promoted to the rank of Professor of Literary Studies in 1983. He retired to Australia in 2002 and was made an honorary research fellow in the Department of English at the University of Adelaide. He is an essayist, a novelist, literary critic, linguist, translator and professor. He received the Irish Times International Fiction Prize in 1995, the Booker Prize in 1999, and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2003.

Bio prepared by Divine Che Neba, nebankiwang@yahoo.com and Didymus Duanla Tsangue University of Yaoundé 1, diddytsangue@yahoo.ca

Adaptations

An adaption of Plato’s The Republic.

Translation

Dutch: Dagboek van een slecht jaar, trans. Peter Bergsma, Amsterdam: Cossee, 2007.

Greek: Ημερολόγιο μιας κακής χρονιά́ς [Īmerológio mias kakī́s chroniás], trans. Athīná Dīmītriádou, Athens: Metaichmio, 2007.

Spanish: Diario de un mal año, trans. Jordi Fibla, Barcelona: Mondadori, 2007.

Danish: Dagbog fra et dårligt år, trans. Niels Brunse, Copenhagen: Hekla, 2008.

French: Journal d'une année noire: roman, trans. Catherine Lauga du Plessis, Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2008.

German: Tagebuch eines schlimmen jahres, trans. Reinhild Böhnke, Frankfurt a.M.: S. Fischer, 2008.

Norwegian: Et dårlig år, trans. Mona Lange, [Oslo]: Cappelen Damm, 2008.

Polish: Zapiski ze złego roku, trans. Michał Kłobukowski, Kraków: Znak, 2008.

Portuguese: Diário de um ano rium, trans.José Rubens Siqueira, São Paulo: Companhia das letras, 2008.

Portuguese: Diário de um mau ano: romance, trans. J. Teixeira de Aguilar, Alfragide: Dom Quixote, 2008.

Chinese: 凶年纪事 [Xiong nian ji shi], trans. Wen Min yi, Hangzhou Shi: Zhejiang wen yi chu ban she, 2009.

Romanian: Jurnalul unui an prost, trans. Irina Horea, București: Humanitas Fiction, 2009.

Turkish: Kötü bir yılın güncesi: roman, trans. Suat Ertüzün, İstanbul: Can Sanat, 2009.

Finnish: Huonon vuoden päiväkirja, trans. Seppo Loponen, Helsinki: Otava, 2010.

Russian: Дневник плохого года [Dnevnik plokhogo goda], trans. Yuliya Fokina, Moskva: AST Astrelʹ, 2011.

Summary

Diary of a Bad Year is an experimental novel (historical fiction) in which non-fiction and fiction are juxtaposed within the same novel. Each page is divided into two or three parts. The novel takes the form of a series of essays that the protagonist is writing for a collection, tentatively called Strong Opinions. These essays take up the first part of the page. Beneath this, are diary entries, both by the central character, and by his young typist, recounting the developing relationship between the two. Thus, the second and third sections contain two narratives: one told from the Señor C’s (the protagonist’s) point of view and the other from his typist’s (Anya) point of view.

One: Strong Opinions: 12 September 2005 – 31 May 2006

“On the origins of the state,” “On anarchy,” “On Machiavelli,” and “On democracy” deal with state politics and governance. They deal with how people choose to enter into the protection of the state in order to avoid internecine warfare; how the concept of democracy is limiting but necessary to forestall civil war; and how people choose to be passive or quiet to the abuses control and enslavement of the state. On the subject of terrorism, he argues in “On terrorism,” “On Al Qaida” and “On guidance system,” that the irrationality of terrorists can be compared to state terrorism, masterminded by western states as a means of oppressing the rest of the world. Consequently, suicide bombing could be a way to combat American sophisticated guidance systems. In “On University,” he decries the cutting of university funds, despite the increase in professors’ works.

The next four essays further criticize the state especially in relation to its use of torture. The next five essays deal with a miscellany of issues from child pornography to the limits of probability.

He returns to the question of politics in “On raiding,” “On apology,”“On asylum in Australia,” “On political life in Australia,” “On Left and Right,” “On Tony Blair,” and “On Harold Pinter”.

The last set of essays handles different serious issues. In “On Music,” he discusses different kinds of music, and how Africans in the new world colonize former colonizers with their soulful music. In “On Tourism,” he recounts how he toured the same places that Ezra Pound toured and was not as inspired as he expected to be. In “On English usage,” he decries the declining standards of English, particularly, the use of prepositions. “On authority in fiction” expresses admiration for Tolstoy’s masterly building of authority in fiction and “On the afterlife” criticizes the Christian notion of the afterlife.

Two: Second Diary

The second diary is called soft opinions, and according to the letter in Señor C’s narrative, they were written after Anya had left, implying that they were typed by someone else. They cover a wide variety of topics ranging from emotion, religion, the city to children and music.

The two narratives

There are two narratives of the experiences of Señor C and Anya while they are working on the Strong Opinions book, told from each person’s point of view. It begins when Señor C spots Anya in the laundry room dressed in a provocatively short red dress that exposes her seductive behind. Anya is aware of his eyes on her and decides to seduce him by wiggling her behind. Señor C falls for it, and shortly afterwards, approaches her with a proposal for her to type his “strong opinions” for a book he has been commissioned to contribute to by a German publisher. As the work progresses a strange kind of romantic relationship develops between Señor C (70 years) and Anya (29 years). They start by arguing about some of the opinions. Anya argues that from her experience in the 21st century, when a man rapes a woman, the shame is on the man. Señor C argues that the shame still sticks on the woman like bubble gum, because things have not changed completely. Anya also discusses her boyfriend, Alan, with Señor C. In the course of the discussion, Anya realizes that Alan has been spying on her by stealthily reading Señor C’s opinions. She confronts him and he admits that he had installed a spyware on the old man’s computer and so knows everything that is in it. He proposes that they steal his money but Anya refuses. After learning of Señor C’s opinions, Alan dismisses them as issues far removed from the present times, especially present day Australia. He thinks Señor C is mentally and psychologically stuck in Africa where there are still big issues in politics.

When the work is done, Señor C organizes a party for three of them to celebrate its completion – himself, Anya and Alan. Alan agrees to go despite his suspicions about the old man’s motives. At the party they are surprised to find that they are the only guests. Alan however gets drunk and begins to talk too much. He accuses the old man of running after his girlfriend, and informs him that he had wanted to steal his money but Anya saved him. Anya is mortified by this behavior and when they leave, she vows never to forgive Alan. They break up and Anya goes to live with her mother. The book is eventually published and Senor C sends a copy to Anya. Though it is in German, she promises to keep it as a memento. She writes a long letter to Señor C in which, among many other things she admits her feelings for him and appreciates the fact that he was a kind and respectful gentleman.

Analysis

Most of the topics in Diary of a Bad Year parallel those in Plato’s The Republic: “Socrates considers a tremendous variety of subjects such as several rival theories of justice, competing views of human happiness, education, nature and the importance of philosophy and philosophers, knowledge … good and bad political regimes, the family, the role of women in society, the role of art in society, and even the afterlife” (see source here, accessed: November 19, 2018). The dialogue between Señor C and Anya over their views on shame and dishonor ends in a deadlock thereby inviting the reader to make their own decision. Likewise, in Plato, the reader also shares in a dialogue and is also asked to weigh their ideas against those presented by Socrates and his interlocutors. Some critics have pointed out some similarities and differences between the dialogues in Coetzee and the Socratic dialogues presented in The Republic. Both of them are involved in the removal of obstacles in order to give a better platform for the reader to discover the truth. However, as Wilm argues*, the epistemological impact between Plato and Coetzee’s Socratic Method differs in that in Plato, the reader is enjoined to think and attain the truth, negotiate ideas, and learn the truth while being passive and following the lead of Socrates who knows the final truth. For his part, Coetzee puts obstacles in the part of the reader from the beginning and allows them to deal with them intellectually and find the truth for themselves (161).

In books I, II and VIII of The Republic, Socrates argues with Cephalus, Polemarchus, Thrasymachus and Adeimantus about old age and justice, both at the individual and state levels particularly in Book VIII. Among other things, he talks about the limits of democracy as well as other forms of governance, such as oligarchy, aristocracy, and timocracy. Just as Coetzee argues in On the origins of the state, Socrates argues that humans enter into political life due to the inability of nature to provide everything they need. He also talks about how rulers should be selected (book 3). He argues for gender equality in Book V, especially in relation to defending the city. He also discusses the education of the philosopher king in Book VI and VII. Like Plato in Book IX, Coetze also discusses tyrannical individuals and states Book.

* Wilm Jan, The Slow Philosophy of J. M. Coetzee, Bloomsbury: London, 2017.

Further Reading

Abbott, Porter H., "Time, Narrative, Life, Death, & Text-Type Distinctions: The Example of Coetzee's "Diary of a Bad Year"", Narrative 19.2 (2011): 187–200 (accessed: September 8, 2021).

Coumoundouros, Antonis, “Plato: The Republic”, The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, iep.utm.edu (accessed: November 19, 2018).

Geertsema, Johan, "Coetzee's "Diary of a Bad Year," Politics, and the Problem of Position", Twentieth Century Literature 57.1 (2011): 70–85 (accessed: September 8, 2021).

Leist, Anton, and Peter Singer, eds., J. M. Coetzee and Ethics: Philosophical Perspectives on Literature, New York: Columbia University Press, 2010.

McDonald, Peter D., "The Ethics of Reading and the Question of the Novel: The Challenge of J. M. Coetzee's Diary of a Bad Year", NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction 43.3 (2010): 483–499 (accessed: September 8, 2021).

Ogden, Benjamin H., "The Coming into Being of Literature: How J. M. Coetzee's Diary of a Bad Year Thinks through the Novel", NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction 43.3 (2010): 466–482 (accessed: September 8, 2021).

Rose, Arthur, and Chull Wang, "Questions of Hospitality in Coetzee's "Diary of a Bad Year"", Twentieth Century Literature 57.1 (2011): 54–69, (accessed September 8, 2021).

Wilm, Jan, The Slow Philosophy of J. M. Coetzee, Bloomsbury: London, 2017.