Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Philippos Mandilaras, Απόλλωνας και Άρτεμη [Apóllōnas kai Ártemī], My First Mythology [Η Πρώτη μου Μυθολογία (Ī prṓtī mou Mythología)]. Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2012, 36 pp.

ISBN

Available Onllne

Demo of 6 pages available at epbooks.gr (accessed: October 13, 2021).

Genre

Illustrated works

Target Audience

Children (Reader: 4+)

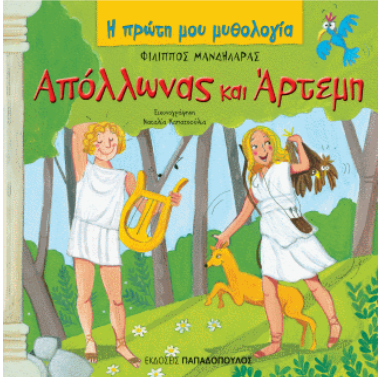

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher. Retrieved from epbooks.gr (accessed: July 5, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Natalia Kapatsoulia (Illustrator)

Natalia Kapatsoulia studied French Literature in Athens, and she worked as a language tutor before embarking on a career as a full-time illustrator of children’s books. Kapatsoulia has authored one picture book Η Μαμά πετάει [Mom Wants to Fly], which has been translated into Spanish Mamá quiere volar. Kapatsoulia, who now lives on the island of Kefalonia, Greece, has collaborated with Filippos Mandilaras on multiple book projects.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Profile at the epbooks.gr (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Filippos Mandilaras

, b. 1965

(Author)

Filippos Mandilaras is a prolific and well-known writer of children’s illustrated books and of young adults’ novels. Mandilaras studied French Literature in Sorbonne, Paris. His latest novel, which was published in May 2016, is entitled Υπέροχος Κόσμος [Wonderful World], and it recounts the story of teenage life in a deprived Athenian district. With his illustrated books, Mandilaras aims to encourage parents and teachers to improvise by adding words when reading stories to children. Mandilaras is interested in the anthropology of extraordinary creatures and his forthcoming work is about Modern Greek Mythologies.

Sources:

In Greek:

Profile on EP Books' website (accessed: June 27, 2018).

i-read.i-teen.gr (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Public Blog, published 15 September 2015 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Press Publica, published 28 January 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Linkedin.com, published published 6 May 2016 (accessed: February 6, 2019).

In English:

Amazon.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

On Mandoulides' website, published 7 March 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

In German:

literaturfestival.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Summary

The book starts by showing two gods as small children in a pram. We read that the boy grew up to become a patron of the arts and music, while the girl lived in the forests and hunted. Readers are asked to guess the two siblings’ names. Next, we read about pregnant Leto trying to find a place to give birth, running away from Hera’s frustration with Zeus’ infidelity.

Leto takes refuge in a small island, and gives birth, first to Artemis and then to Apollo. It now becomes clear to readers who the small children are, and that they are twins. Hera sends a dragon, Python, to fight Leto and her children. Apollo chases Python, finds his hiding cave at Delphi, and kills him with his arrows. At the Delphic Oracle, Apollo learned about divination from the Pythia. At the same time, Artemis wandered around the forests, hunting wild beasts. Apollo and Artemis joined forces to kill the giant Tityos with their arrows.

We then read that Zeus was very happy to see Artemis, his daughter, and promised to fulfil all her wishes. Artemis wanted to stay unmarried and live as a huntress. And this was granted. Artemis lived in the forests, in the company of deer. Apollo, on the other hand, became a god of music, light, the arts, and divination, and he lived in the skies. Apollo had many adventures. He chased Daphne, but she turned herself into a plant. He was good friends with Hyacinth. Zephyros was envious of the friendship, and killed Hyacinth with a discus. Apollo turned his friend’s blood into flowers. Apollo loved Kassandra, the princess of Troy, but she rejected him. Apollo cursed her to foresee the future.

We read that Artemis had adventures also. When Aktaeon saw her bathing, she turned him into a deer. Orion boasted that he was a better hunter than Artemis, and she killed him. Artemis, nonetheless, was also compassionate, and saved Iphigeneia from being sacrificed.

The narrative ends with a depiction of modern tourists visiting ancient ruins. Visitors to Brauron and Delphi may think that the two gods still live there. The book closes by offering background information about Apollo, Artemis, and Delphi, as well as an exercise wherein children are asked to associate things and animals with either Apollo or Artemis.

Analysis

In a concise manner, the book covers Apollo’s and Artemis’ roles within the Greek pantheon, multiple mythological episodes, and the gods’ key attributes, the lyra and the deer, respectively. There is considerable emphasis on family ties, which presumably helps with children’s learning of stories and names from the distant past. Leto cares for her children. The twins assist and complement each other. Zeus dearly loves his daughter whom, as we read, he hugs, takes on his lap, and fills with kisses. The portrayal of the latter appears to have potent connotations for a western, and possibly feminist, upbringing. Artemis, although a young child judging from her small size in the illustration, stands with confidence before her father and articulates a long list of demands. She is someone who knows what she wants. She makes a point about wishing to be unconventional, to live in the mountains, and not to marry.

Appropriately, natural landscapes and greenery dominate in the illustrations. Green is a colour that is almost unknown in Greek art, given its limited presence, if any, on artefacts that range from Mycenaean frescoes (ca. 1500–1200 BCE) to Attic white polychrome lekythoi (5th century BCE). In the book, green defines the forests of huntress Artemis, but also the plains where the killings of Python and Tityos take place. The protagonists appear to act in an undomesticated context that has almost nothing to do with the world of mortals. We read, moreover, that Apollo could fly in the sky and be close to anyone that needed him. Artemis is shown flying, as she carries Iphigeneia away from Aulis. Open spaces appear to grant the two deities freedom, as well as high mobility in ways that humans could not have.

There are elements in the textual and pictorial narrative that align the content of the book here with modern visual media. The green dragon may remind readers of dinosaurs. More impressively perhaps, the dragon could call to mind folk tales wherein dragons, like Python at Delphi, guard water sources. Leto, Apollo, and Artemis are all shown with blond hair, and this may resonate with contemporary ideas of beauty, especially in Hollywood movies.

It may become questionable, then, whether Apollo and Artemis are represented as deities. The religious significance of Delos and Delphi seem to be downplayed in the book. Delos is not described as a cult place, as confirmed archaeologically. It is only at the last page that we read that Apollo and Artemis were venerated in temples in ancient Greece. Throughout the book, Apollo and Artemis stage a performance, first as children and then as young adults (who never grow old). They are constantly on the move, and have adventurous encounters with significant others, often with a sad ending as highlighted by Hyacinth’s death. Their fate, therefore, is marked also with misfortune, and in these respects mirrors the lives of mortals. Classical myth has been sanitized for children. While sexuality has been removed, violence and death remain. Sad events may aim to help children to develop coping mechanisms.

Addenda

Published in Greek, 13 December 2012. Hardbound.

Information about the book:

epbooks.gr (accessed: February 6, 2019).