Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

René Goscinny & Albert Uderzo, “Astérix aux Jeux olympiques”, Pilote, 1968, 434–455.

René Goscinny & Albert Uderzo, Astérix aux Jeux olympiques, Paris: Dargaud, 1968, 44 pp.

ISBN

Official Website

Genre

Action and adventure comics

Comics (Graphic works)

Historical fiction

Humor

Illustrated works

Target Audience

Crossover

Cover

We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover.

Author of the Entry:

Richard Scully, University of New England, Armidale rscully@une.edu.au

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

René Goscinny

, 1926 - 1977

(Author)

René Goscinny was born in 1926 in Paris. He was the son of Jewish immigrants to France from Poland. Born in Paris, he moved with his family to Buenos Aires, Argentina, at the age of two. In 1943 he was forced into work by his father’s death, eventually gaining work as an illustrator in an advertising firm. Living in New York by 1945, Goscinny was approaching the usual age of compulsory military service. However, rather than join the United States Army, he elected to return to his native France to complete its year-long period of service. Throughout 1946, Goscinny was with the 141st Alpine Infantry Battalion, and found an artistic outlet in the unit’s official and semi-official posters and comics. His first commissioned illustrated work followed in 1947, but he then entered into a period of hardship upon moving back to New York City. Some important networking occurred thereafter with other emerging comic artists, before Goscinny returned to France in 1951 to work at the World Press Agency. There, he met lifelong collaborator, Albert Uderzo, with whom he co-founded the Édipresse/Édifrance syndicate and began publishing original material.

As Edipresse/Edifrance developed, Goscinny continued to work across a number of publications in the 1950s, including Tintin magazine from 1956. A key output from this period was a collaboration with Maurice De Bevere (1923–2001). They created together series of comics: about Lucky Luke (with Maurice), and about Asterix (with Uderzo). Goscinny worked with Jean Jacques Sempe and they created a series about boy called Nicolas.

The following year (1959), the syndicate launched its own magazine, Pilote; and the first issue contained the earliest adventure of ‘Astérix, the Gaul’, scripted by Goscinny himself, and drawn by Uderzo. On the back of Astérix, Pilote was a huge success, but managing a magazine was a challenge for the members of the syndicate. Georges Dargaud (1911–1990) – publisher of Tintin, and a major force in Franco-Belgian comics – saw the opportunity to purchase Pilote in 1960, and put it on a firmer footing, financially. Already the leading script-writer on the magazine, Goscinny was co-editor-in-chief of Pilote from 1960. Such was its success that by 1962, he was able to leave Tintin magazine in to edit Pilote full-time, and he held that role until 1973.

Goscinny’s success with Astérix and Lucky Luke (published in serialized instalments in the magazine, as well as in album-form by Dargaud) saw him enjoy a comfortable life, but this arguably contributed to his growing ill-health. He had married in 1967 – to Gilberte Pollaro-Millo – and a daughter – Anne Goscinny – was born the following year, as he continued to work with Uderzo and others. Pilote and Astérix were sufficiently profitable to be a full-time job, and twenty-three Astérix adventures were completed by 1977, when Goscinny died suddenly of a cardiac arrest during a routine stress test. Uderzo completed the story Astérix chez les Belges [Asterix in Belgium] and continued the series alone.

Goscinny was not only a comic book author but also a director and co–director of animated movies (Daisy Town, Asterix and Cleopatra), feature movies (Les Gaspards, Le Viager). Goscinny. He died in 1977 in Paris.

Sources:

bookreports.info (accessed: September 14, 2018)

britannica.com (accessed: September 14, 2018)

lambiek.net (accessed: September 14, 2018)

Bio prepared by Agnieszka Maciejewska, University of Warsaw, agnieszka.maciejewska@student.uw.edu.pl and Richard Scully, University of New England, Armidale rscully@une.edu.au

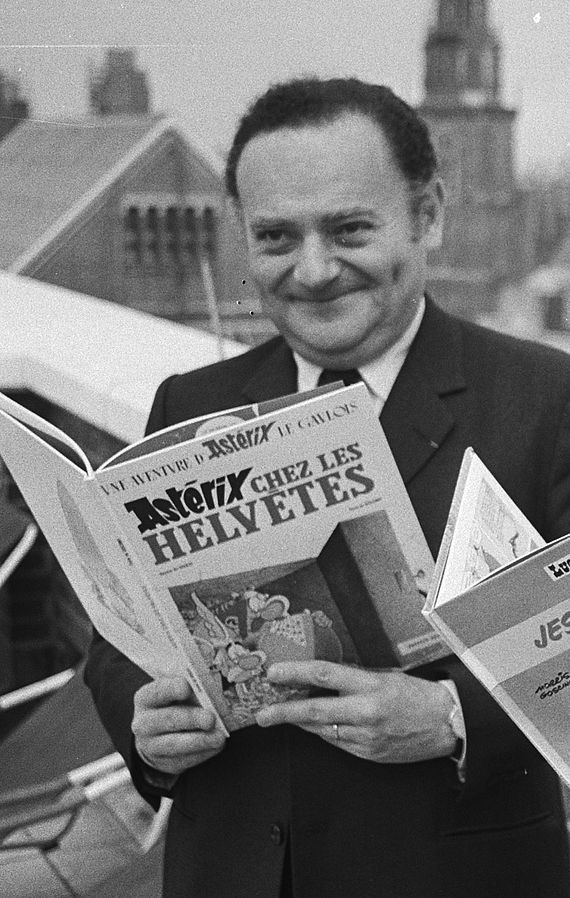

Albert Uderzo in 1973 by Gilles Desjardins. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 (accessed: December 30, 2021).

Albert Uderzo

, 1927 - 2020

(Illustrator)

Albert Uderzo was born in Fismes, France, in 1927. The son of Italian immigrants, he experienced discrimination following the family’s move to Paris, at a time when Fascist Italy was pursuing an aggressive course, internationally (on top of the usual xenophobia directed at immigrants). Uderzo came into contact with American-imported comics around the late 1930s (including Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck). He also discovered that he was colour-blind (despite art being the only successful aspect of his schooling career). Living in German-occupied France, from 1940, Uderzo tried his hand at aircraft engineering, but illustration was where he found his métier. Post-war, he came into contact with the circles of Belgian-French comics artists; as well as meeting and marrying Ada Milani in 1953 (who gave birth to a daughter, Sylvie Uderzo in 1953).

He started his career as an illustrator after World War II. In 1951, he met René Goscinny at the World Press Agency. Together, they worked on a comic: ‘Oumpah-pah le Peau-Rouge’ [Ompa-pa the Redskin] – drawn by Uderzo and written by Goscinny. In 1959 Uderzo and Goscinny were editors of Pilote magazine. They published there their first Asterix episode which became one of the most famous comic stories in history. Individual albums of Astérix adventures appeared regularly from 1961 (published by Georges Dargaud following the completion of the serialized run in Pilote), and there were 23 completed adventures by the time Goscinny died in mid-1977. After Goscinny’s death, Uderzo took over the writing and continued publishing Asterix adventures, and completed 11 further albums by retirement in 2011 (including several that were compendiums of older material, co-created by Goscinny). In the late 2000s and early 2010s, Uderzo experienced considerable family disquiet; largely over the financial benefits expected to accrue to his daughter. Although maintaining for much of his career that Astérix would end with his death, he agreed to sell his interest in the character to Hachette Livre, who has continued the series since 2011, owing to the talents of Jean-Yves Ferri and Didier Conrad.

All stories about Asterix published till now are very successful and widely known. They are highly popular not only in France but have been translated into one hundred and ten languages and dialects. The series continues and Asterix (Le papyrus de Cesar) became the number one bestseller in France in 2015 with 1,619,000 copies sold. The sales figures and popularity of Asterix series are comparable with the Harry Potter phenomenon. Astérix et la Transitalique published in “2017 placed 76 among the French Amazon best sellers three weeks before it was published Among comic books for adolescents the title was number one, among comic books of all categories it was number two.”*

Albert Uderzo died on 24 March 2020.

Sources:

lambiek.net (accessed September 14, 2018).

Bio prepared by Agnieszka Maciejewska, University of Warsaw, agnieszka.maciejewska@student.uw.edu.pl and Richard Scully, University of New England, Armidale rscully@une.edu.au

*See Elżbieta Olechowska, “New Mythological Hybrids Are Born in Bande Dessinée: Greek Myths as Seen by Joann Sfar and Christophe Blain” in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Chasing Mythical Beasts…The Reception of Creatures from Graeco-Roman Mythology in Children’s & Young Adults’ Culture as a Transformation Marker, forthcoming.

Adaptations

Astérix aux Jeux olympiques was adapted as a feature-film by Frédéric Forestier and Thomas Langmann in 2008, as part of the general effort to give a boost to the French cinema industry during the Global Financial Crisis of the mid-to-late 2000s. The third live-action film (following Astérix & Obélix contre César, 1999; and Astérix et Obélix: Mission Cléopâtre, 2002), the comic narrative was extremely loosely adapted, and new elements (a love interest, the inclusion of Marcus Junius Brutus as villain) greatly altered the story. Starring Gérard Depardieu (Obelix) and Clovis Cornillac (Astérix), the film was the most expensive French and non-Anglophone film ever made (budgeted at US$113.5 million), but received poor reviews, despite performing very well internationally (taking $133 million in box office revenues; including strong showings in Poland, Spain, and France; but with weaker results in Germany, Italy, and Belgium).

The merchandising associated with the film included a PC, Nintendo Wii, Sony Playstation 2 and Nintendo DS video game of the same name. Developed by Atari Europe, the players (maximum of 2) compete in various Olympic events to advance the storyline. It received neutral to moderately good reviews, and sold well enough to merit an Xbox 360 release in 2008.

Translation

Afrikaans: Asterix en die Olimpiese Spele, Cape Town: Human and Rousseau Ltd., 1997.

Afrikaans: Asterix by die Olimpiese Spele, Pretoria: Protea Boekhuis, 2006.

Alsatian: De Asterix ān de olympische Spieler, Paris: Verlaa Dargaud (Dargaud Editeur), 1996.

Greek: Αστερικιος εν Ολυμπια [Asterikios en Olympia], Athens: Mamouth Comix Ltd., 1992.

Basque: Asterix joku Olinpikoetan, Barcelona: Elkar / Grijalbo-Dargaud, 1989.

Basque: Asterix olinpiar Jokoetan, Barcelona: Salvat Editores, 2016.

Bengali: Olympic e Asterix, Calcutta: Ananda Publishers Pvt, 2015.

Bulgarian; Астерикс на олимпийските игри [Asteriks na olimpijskie igri], Sofia: Egmont Bulgaria Ltd., 1996.

Catalan: Astèrix als jocs olímpics, Barcelona: Bruguera, 1969.

Catalan: Astèrix als jocs olímpics, Barcelona: Salvat Editores, 1977.

Chinese: 阿斯特克斯参加奥运会 [Āsītèkèsī cānjiā Àoyùnhuì], Beijing: Xinxing New Star, 2014.

Cretan: Ο Αστερικακης στις Ολιμπιακές συνορισές [O Asterikakīs stis Olimpiakes synorises], Athens: Mamouth Comix Ltd., 2007.

Croatian: Asterix na Olimpijskim igrama, Zagreb: Izvori Publishing House, 1996.

Cypriot: Ο Αστερικκος στους Ολυμπιακους αγονες [O Asterikkos stous Olympiakous agones], Athens: Mamouth Comix Ltd., 2007.

Czech: Asterix a Olympijské hry, Prague: Egmont ČR, 1995.

Danish: Olympisk mester! Copenhagen: Egmont Serieforlaget A/S, 1972.

Dutch: De Olympische spelen, Amsterdam: Hachette, 1972.

English: Asterix at the Olympic Games, Leicester: Brockhampton, 1972.

English (US): Asterix at the Olympic Games, New York: Dargaud Publishing International. Distributed by Distribooks inc., 1992.

Esperanto: Asteriks kaj la Olimpikaj Ludoj, Zagreb: Izvori Publishing House, 1996.

Estonian: Asterix olümpiamängudel, Tallinn: Egmont Estonia, 2000.

Finnish: Asterix olympialaisissa, Helsinki: Egmont Kustanus Oy, 1970.

Galician: Astérix Nos Xogos Olímpicos, Barcelona: Editorial Galaxia - Grijalbo-Dargaud, 1996.

German: Asterix bei den Olympischen Spielen, Stuttgart: Egmont Ehapa, 1972.

Greek: Αστερίξ Ολυμπιονίκης [Asterix Olympionikīs], Athens: Spanos Editions, 1969.

Greek: Ο ’Αστερίξ Ολυμπιονικης [O Asterix Olympionikīs], Athens: Anglo Hellenic Agency, 1979.

Greek: Ο Αστεριξ στους Ολυμπιακους Αγωνες [O Asterix stous Olympiakous Agōnes], Athens: Mamouth Comix Ltd., 1992.

Hebrew: אסטריקסבאולימפידה, Tel Aviv: Dahlia Pelled Publishers Ltd., 2007.

Hessisch: Fix un ferdisch, Schtuttgart: Ehaba Verlaach, 2000.

Hindi: Estriks Olampik Me, New Delhi: Gowarsons Publishers Private Ltd., 1982.

Hungarian: Asterix az Olimpián, Novi Sad: Yugoslav publisher Nip Forum, 1968.

Hungarian: Asterix az Olimpián, Budapest: Móra Könyvkiadó, 2012.

Icelandic: Ástríkur (smár en knár) Ólympíukappi, Reykjavik: Fjölvi HF, 1975.

Indonesian: Asterix di Olympiade, Jakarta: Pt. Sinar Harapan, 1987.

Italian: Asterix alle Olimpiadi, Verona: Mondadori, Verona, 1972.

Italian: Asterix alle Olimpiadi, Milan: Fabbri-Dargaud, 1983.

Korean: 아스테릭스, 올림픠에나가다, Seoul: Moonhak-kwa-Jisung-Sa, 2001.

Latin: Asterix Olympius, Leicester: Brockhampton, 1972.

Latin: Asterix Olympius, Stuttgart: Egmont Ehapa Verlag, 2000.

Luxembourghish: Den Asterix op der Olympiad, Luxembourg: Editions Saint-Paul, 1988.

Norwegian: Olympisk mester, Oslo: Egmont Serieforlaget AS, 1972.

Persian: آستريکس در بازی های المپیک / Asterix at the Olympic Games, Teheran: Partov Vaghee / Saamer, 2010.

Polish: Asteriks na Igrzyskach Olimpijskich, Warsaw: Egmont Poland Ltd., 1993.

Polish: Asteriks na Igrzyskach Olimpijskich, Warsaw: Egmont Poland Ltd., 1999.

Pontic: Ο Αστερικον σα Ολυμπιακα Τ'Αγονας [O Asterikon sa Olympiaka T'Agonas], Athens: Mamouth Comix Ltd., 2007.

Portuguese: Astérix nos jogos olímpicos, Lisbon: Meribérica-Liber., 1968.

Portuguese (Brazilian): Asterix nos Jogos Olímpicos, Rio de Janiero: Record Distribuidora, 1972.

Russian: Астерикс на Олимпийских играх [Asteriks na Olimpijskih igrah], Moscow: Hachette, 2011.

Serbian: Астерикс на Олимпијским Играма [Asteriks na Olimpijskim Igrama], Belgrade: Политика / Politika, 1996.

Serbo-Croatian: Asteriks na Olimpijadi, Novi Sad: NIP Forum, 1980.

Slovak: Asterix na olympijských hrách, Bratislava: Egmont, 1995.

Slovenian: Asterix na olimpiadi, Radovljica: Didakta, 1992.

Spanish: Asterix en/y los Juegos Olimpicos,Barcelona: Salvat Editores, 1968.

Spanish (American): Asterix en los Juegos Olimpicos, Buenos Aires Editorial Abril, 1976.

Steirisch: Asterix ba di Olümpschn Schpüle, Vienna: Egmont Valog, 2000.

Swedish: Asterix på olympiaden, Malmö: Egmont Kärnan AB, 1972.

Turkish: Bücür (cilt 1): Olimpiyatlarda, (no. 1-3) sayi: Istanbul: Serdar Yayınları.

Turkish: Asteriks olimpiyatlarda, Istanbul: Kervan Kitabçilik, 1977.

Turkish: Asteriks Olimpiyatlarda, Istanbul: Remzi Kitabevi, 2000.

Vietnamese: Aterich tham dự thế vận hội, Hanoi: Thien-Nga (bootleg edition), 1973.

Vietnamese: Asterix Doi thu dang so & Asterix chien thang khong can suc manh [two parts], Hanoi: NhaXuatBanTre (bootleg edition), n.d.

Welsh: Asterix yn y gemau Olympaidd, Cardiff: Gwasg Y Dref Wen, 1979

Welsh: Asterix yn y gemau Olympaidd, Ceredigion: Dalen, 2012

Summary

"In 50 BC, Gaul is entirely occupied by the Romans. Well… not entirely. One small village of indomitable Gauls still holds out against the invaders." The Gauls are aided by a magic potion which gives them superhuman strength, and is brewed by the druid Panoramix (Getafix in English). In late spring, the inhabitants of the village learn that the neighbouring Roman camp of Aquarium is preparing to send its champion – Claudius Cornedurus (corne d'urus, Gluteus Maximus in English) – to compete in the Olympic Games in Greece, between July and August. Although Romans are the only non-Greeks permitted to compete, the warrior Astérix claims that – since Caesar’s conquest – his people are Romans, and therefore able to participate. A "Gallo-Roman Team" is assembled (consisting of Astérix and his great friend, Obélix) and the entire male population of the village sets out for Greece by sea. They sail via Hispania, Mauretania and Numidia (encountering and besting a pirate galley on the way), and arrive in Piraeus before going up to Athens as tourists, and on to Olympia itself. The Gauls’ presence creates havoc amongst the disciplined Greek and Roman athletes. The Gauls’ planned use of the magic potion is discovered, and prohibited by the Olympian authorities, so Astérix elects to compete without it (Obélix is banned, because he fell into a cauldron of magic potion as a baby, and is permanently affected). The games produce a clean-sweep for Greek athletes, but the Olympic Senate decides to hold a "Romans Only" event. Astérix and Panoramix (Getafix) (and the clueless Obélix) trick the Roman athletes into taking doses of the magic potion the night before the event, and when their cheating is discovered (their tongues dyed blue from a dye added to the cauldron by Panoramix (Getafix)), Asterix is declared the winner, and returns in triumph to his village. In a typically noble gesture, Astérix gifts his palm-leaf of victory to Claudius Cornedurus (Gluteus Maximus), who is honoured by Caesar in Rome.

Analysis

Astérix aux Jeux olympiques was the twelfth adventure to feature the village of indomitable Gauls, written by Goscinny and designed by Uderzo. By its publication (1968) the adventure comic was at the pinnacle of its popularity and attracted enormous praise for its light-hearted play on the ancient world, and the humorous anachronistic imagining of personalities and events that mirrored the present-day.

The book was produced to coincide with the Games of the XIX Modern Olympiad (held in October in Mexico City), and Goscinny and Uderzo took the opportunity to engage with Ancient Greek history for the first time since commencing the Astérix series in 1959. Prior adventures had highlighted the relationship between the Gaulish tribes and the Roman conquerors; the close cross-Channel affinity with the British; the antagonism across the Rhine with the Goths/Germans; the customs of the Gauls; the late Ptolemaic Egypt of Cleopatra VII; and an ahistorical encounter with ‘Normans’. For the historical background, Goscinny consulted generalist texts such as the Histoire de Rome of André Piganiol (1954); Jérôme Carcopino’s La vie quotidienne à Rome à L’apogêe de l'Empire (1939); Paul-Marie Duval’s La vie quotidienne en Gaule pendant la paix romaine (1953); and Lumières sur la Gaule by Henri-Paul Eydoux (1960). The story, though, is not bound by historical accuracy, and the behaviour of the Gauls resembles more of a romanticised French rural life; the Romans are bumbling fools; and while the Greeks – all related to each other – possess variations on the ‘classical’ profile (aquiline noses, dark hair; geometric-patterned chitons), they behave very much like the mid-to-late 1960s Greeks encountered regularly on tourist excursions (and the Gauls are taken for a ride by an unscrupulous travel agent, who forces them to row all the way to Greece in his galley and charges extra for virtually everything).

In a further nod to the ancient context, the text in the Greeks’ speech-bubbles is deliberately rendered in a faux Hellenic script (indicating the accent of the speakers), while the speech of Romans and Gauls is rendered in a normal, western-style script (Egyptians speak in amusing hieroglyphics). The Roman centurion – Tullius Mordicus (Gaius Veriambitius in English) – occasionally drops in a Latin phrase (Et nunc, reges, intelligite, erudimini, qui judicati terram: “And now, kings, understand; you who decide the fate of the Earth, educate yourselves” – Psalm 2: 10). The Gauls behave as would modern-day French tourists (seeing the Parthenon, eating and drinking late into the night, acquiring all sorts of kitsch souvenirs); and the Olympic games themselves resemble more the modern event: there is training with dumbbells, skipping ropes, and using other gym equipment; national pride in sporting culture is evident, and the reference to performance-enhancing drugs is key to the plot. Joking asides regarding women’s non-participation, an all-powerful Olympic Committee, and the political implications of winning (e.g. Caesar rewarding Claudius Cornedurus (Gluteus Maximus)) are all more relevant to the modern than the ancient world. Such asides tend to be less overtly political, and more akin to ‘crossover’ elements intended to amuse more mature readers.

Immensely popular worldwide, Astérix aux Jeux olympiques was translated into English, German, Portuguese and Brazilian Portuguese, Danish, Arabic, Finnish, Dutch, Icelandic, Italian, Japanese, Norwegian, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, and Latin by 1972; Dargaud licensed eighteen separate publishers at that same time, largely to capitalize on the XXth Modern Games (held in Munich). The official website lists 31 different editions currently in print (in 2019) in a variety of languages, and over 50 different translations printed since 1968 (including in obscure languages and dialects of Europe such as Cretan, Hessich, and Luxembourger).

Further Reading

Chatenet, Aymar de, ed., René Goscinny Au-delà du rire, Paris: Hazan – Hachette, 2017.

Clark, Andrew, "Imperialism in Asterix", Belphégor: Littérature Populaire et Culture Médiatique 4.1 (2004), at: dalspace.library.dal.ca (accessed: April 15, 2019).

Kessler, Peter, The Complete Guide to Asterix, London: Hodder, 1995.

Schuddeboom, Bus and Kjell Knudde, "René Goscinny", Lambiek Comiclopedia, at: www.lambiek.net (accessed: April 15, 2019).

Wylie, Jonathan, "Asterix Ethnologue: Anthropology Beyond the Community in Europe", Current Anthropology 20.4 (1979): 797–798.

Addenda

René Goscinny & Albert Uderzo, Asterix at the Olympic Games, translated by Anthea Bell and Derek Hockridge. Leicester: Brockhampton, 1972.