Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Details

Wole Soyinka, The Bacchae of Euripides: A Communion Rite. New York: W. Norton & Company, 1974.

ISBN

Genre

Adaptations

Drama

Target Audience

Age restriction 18+

Cover

We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover.

Author of the Entry:

Divine Che Neba, University of Yaounde 1, nebankiwang@yahoo.com

Chester Mbangchia, University of Yaoundé 1, mabangchia25@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaoundé 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

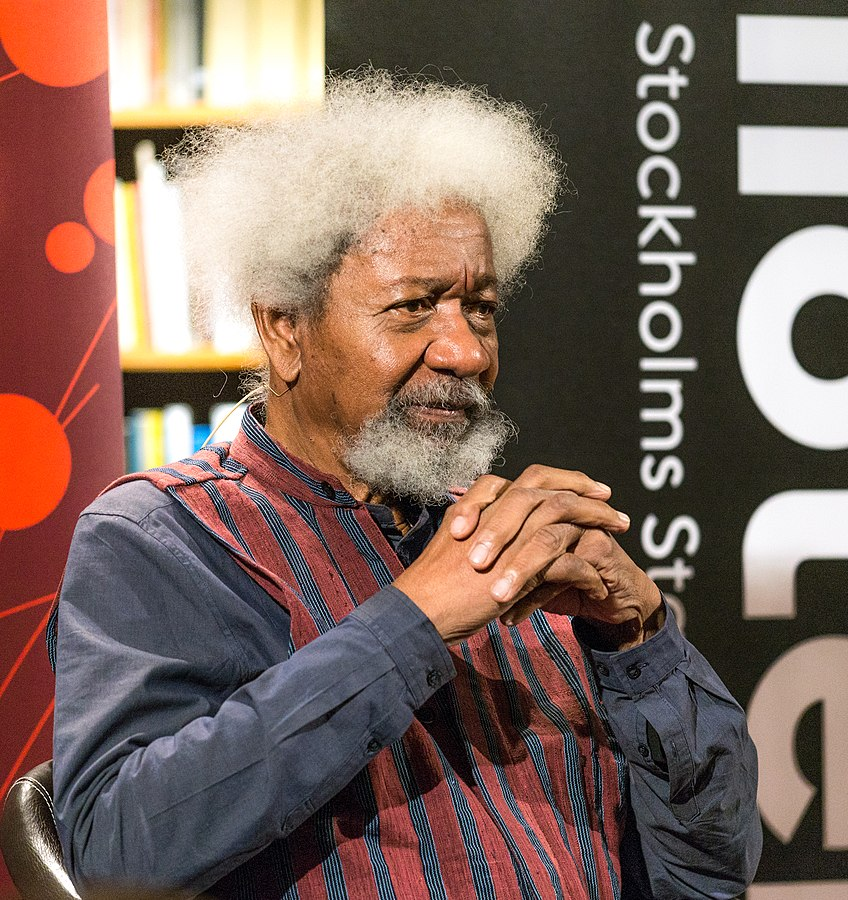

Wole Soyinka by Frankie Fouganthin. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 (accessed: December 30, 2021).

Wole Soyinka

, b. 1934

(Author)

Akinwande Oluwole Babatunde Soyinka (Wole Soyinka) is a Nigerian poet, playwright, and essayist who, in 1986, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, and the Academy of Achievement Golden Plate Award, 2009. His writings cut across the three main genres of literature: drama, prose, and poetry. Soyinka’s writings capture the traditional African scenery, clash of cultures and the interception of African (particularly his Yoruba) mythologies and other myths of the world. In addition, he is a professor of Comparative Literature. Further, in December 2017, he was awarded the Europe Theatre Prize, falling among the “Special Prize Category”.

Bio prepared by Divine Che Neba, University of Yaounde 1, nebankiwang@yahoo.com and Chester Mbangchia, University of Yaounde 1, mbangchia25@gmail.com

Summary

Attention: age restriction 18+

Soyinka’s Bacchae of Euripides: A Communion Rite, an adaptation of Euripides’ Bacchae, hovers around the tragic demise of the proud king of Thebes (presented as a colonial society, marked by slavery in the text), King Pentheus, an oppressive tyrant, who, because of his pride, objects to the god of wine, Dionysus (presented as a revolutionary leader). As a result, he is punished by the god. Soyinka’s play commences with Dionysus, also called Bacchus, who clearly declares to the Thebans that his return to the land is to ask the people to pay him homage) and counteract false claims made about his mother, Semele and himself (in the form of doubt about his divine birth), and King Pentheus’ refusal to worship him. King Pentheus is reluctant to accept Dionysus as the true son of Zeus and Semele. Rather, he sees Dionysus as a foreigner and a pretender.

Later on, a mob (a group of slaves) beats the blind prophet, Tiresias and through their claims, the reader knows that Tiresias has been chosen as the New Year scapegoat, to rid the society of its ills. The blind prophet is ready to accomplish his task. The flogging is interrupted when Dionysus comes to the people and gives details about the sacrifice that is supposed to be made on Mt. Kithairon. All dress and go to the mountain to bear witness to the rites of the Maenads’ (Dionysus’ followers) reverence to Dionysus. When Pentheus arrives, he is furious to see women participating in rites and is irritated because they are now Dionysus’ followers. Dionysus gets angry at Pentheus’ pride and jealousy and as punishment, casts a spell on him, hypnotising him, and he is to be taken to the mountain for sacrifice.

Led by his mother, Agave, and other women of the land, Pentheus goes to the mountain for the sacrifice, as a king. There, stones are thrown at him and he is killed by his mother. His mother, however, is happy that her son has died to save the people. Kadmos, an elder, gathers Pentheus’ body and hangs it on a pole. After her ecstasy, Agave climbs the ladder, removes her son’s head, nails it to the archway in the palace and is ready to bury the corpse.

Tiresias, the one who was originally meant for the sacrifice, joints the crowd and is happy that in his place, Pentheus has offered himself as the scapegoat of the country and has rid the place of its evils. He also claims that Pentheus’ death is an appeasement to the god that he abandoned. Therefore, the sacrifice has been a glorious one, given that it is beneficial to Pentheus’ soul and the whole country.

Analysis

Attention: 18+

Soyinka bridges the gap between Euripides’ Bacchae and his The Bacchae of Euripides: A Communion Rite, though with some differences. His adaptation shows semblances between the Yoruba gods (Orisas) Obatala and Ogun and the Apollonian and Dionysian gods. He claims, in the introduction to his Communion Rite, that Ogun is the totality of the Apollonian and Dionysian virtues. The title of the play indicates that is an adaptation of its Greek counterpart, despite Soyinka’s addition of Communion Rite to suit his pre-colonial, colonial and postcolonial context. Interestingly, Soyinka painstakingly follows Euripides’ storyline along the introduction of his colonial undertones. He gives prominence to sacrificial rituals like the purification rite, where the blind prophet, Tiresias, offers himself for the cleansing of the land. Moreover, in this adaptation, the chorus, which Euripides uses, is represented by a group of slaves to suit his colonial undercurrents. Soyinka’s version, unlike Euripides’, is about the fate of the community, the relationship between oppressors and the oppressed and the purification of the society. In order for Soyinka to achieve his aim of representing Euripides’ Bacchae as a Nigerian communion rite, Soyinka changes the presentation of Pentheus’ regime in the original Greek version. Unlike Euripides’ version where rebirth is absent at the end, Soyinka’s Pentheus accepts being offered as a sacrifice to cleanse the land. Further, the role assigned to Dionysus differs in both versions. Euripides’ Dionysus is not as mature, masculine, and appealing as Soyinka’s. Soyinka’s Dionysus has restorative qualities in him, although in a vengeful way towards the oppressor, Pentheus, a man consumed by pride and stubbornness. Lastly, Euripides’ version is a tragedy, which ends with the tragic demise of Pentheus and the catharsis on the audince while Soyinka’s is a comedy, as the whole community rejoices at the cleansing of their land. At the end of Euripides’ there is lamentation (at the loss of Pentheus) and exile (of Agave), while in Soyinka’s, the god of wine, Dionysus, triumphs over Pentheus and forgives the royal family. Pentheus’ tragic demise also serves as purification of the land, and the end of his oppressive regime, thus, rejuvenation in a purified society.

Further Reading

Goff, Barbara, "Dionysiac Triangles: The Politics of Culture in Wole Soyinka’s The Bacchae of Euripides" in Victoria Pedrick and Steven M. Oberhelman, eds., The Soul of Tragedy: Essays on Athenian Drama, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005, 73–88.

Conradie, P. J., "Syncretism in Wole Soyinka's play The Bacchae of Euripides". South African Theatre Journal 4.1 (1990): 61–74.