Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

Country of the Recording of the Story for the Database

Full Date of the Recording of the Story for the Databasey

More Details of the Recording of the Story for the Database

Genre

Myths

Target Audience

Crossover

Cover

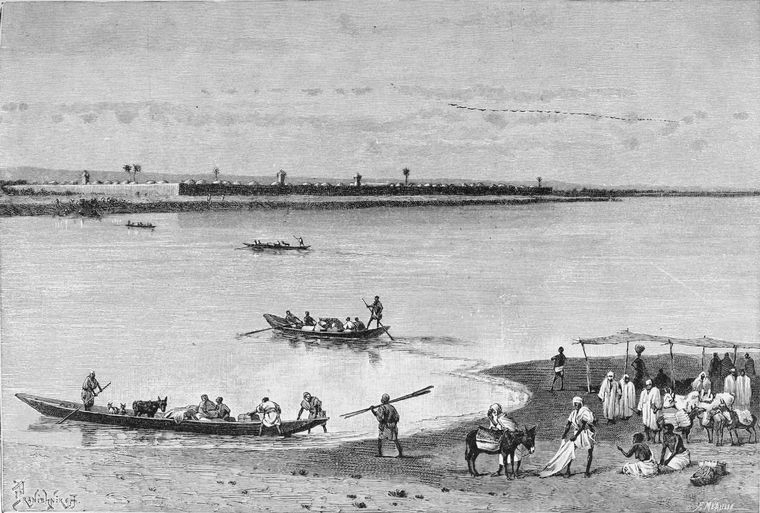

Bank of the Logone River near Logone-Birni. From Elisee Reclus, The earth and its inhabitants, Africa, 1892. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Author of the Entry:

Didymus Tsangue Douanla, University of Koblenz-Landau, douanlatsangue@gmail.com

Aïcha Saïd Larissa, University of Yaoundé 1, larissaichasaid@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaoundé 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Karolina Anna Kulpa, University of Warsaw, k.kulpa@al.uw.edu.pl

Mohamadou Houlaï (Storyteller)

Age of narrator: 76 in 2019)

Social status: Commoner

Profession: Farmer/Petty trader

Language of narration: Arab

Bio prepared by Didymus Tsangue Douanla, University of Koblenz-Landau, douanlatsangue@gmail.com and Aïcha Saïd Larissa, University of Yaoundé 1, larissaichasaid@gmail.com

Origin/Cultural Background/Dating

Occasion: staged

Summary

In the long distant time in the past, the Sao people who live in a very vast territory had all the riches that God bestowed upon them. These included fertile lands, beautiful women and physically strong men. God had an agreement with their leader, where He promised not to refuse any of their requests for additional bounties. These people were unusually very tall and well-built such that they could reach the sky, the house of God, just by stretching up their hand. In the local language it is said that the Soa people could stretch their hands and take from the house of God. The earth was divided into two parts: the part of the Sao people on the one hand, and that of all other people, on the other. One day during their conversation with God, the Sao people requested that God should give them more land because their population was increasing, and that they feared that there might be no living space for their descendants. God told them that it was selfish to nurture the idea that some other people could be eliminated in order for them (the Sao) to have more living space. Since the original pact between the Sao people and God was that God would never refuse any of their requests, they got angry at God for this reply to their demand for land grab. From this point on, they stopped asking anything from God, and were now grabbing everything from God’s house by themselves, since they could stretch their hands to God’s house. Because of this, they became very arrogant towards the other people. One day, they gathered at the centre of the village and decided to dance to manifest their disappointment to God for refusing a request from them. By this collective act, they hoped to mount pressure on God not to renege on his former promise. As they dance in the village square, the weight of their body and strength of their footsteps split open the ground on which they were standing. The cliff that emerged became a large river. This river is today known as River Logone. It is the river that divides Cameroon and Chad. As this happened, God felt that his authority was being challenged by his own creature, and decided in his anger to reduce the height and physical strength of the Sao people, to give to neighbouring people so that they should be equal. According to the myth, this is the reason why today anybody who lives in the area* (Sao people as well as non-Sao people) can give birth to a tall and physically strong person, which was hitherto not the case. The Sao people are now equal to others.

* Now N’djamena in Chad.

Analysis

This myth recounts the early Sao people’s intimacy with God and their subsequent fall from grace as a result of their rebellion. Before that, the early Saos lived in harmony with their God and as a result he allowed them certain privileges and powers. Unfortunately, humans eventually grew in conceit and challenged or abused the benevolence of their maker. As a result, God decided to punitively curtail his gifts and generosity towards them. In Igbo (Eastern Nigeria) mythology, Chinua Achebe likens the fall from God’s grace of the Umuaru people to the fate of the little bird nza, who ate and drank to its fill and challenged its personal deity to a single combat and got what it expected: a thrashing good enough for today and tomorrow (Arrow of God). It also traces the origin of an important physical feature* – the River Logone in the mythic past of the Sao power. The next important element is the depiction of giants in the myth. As Lanier pointed out, this was probably to appeal to children's and young adults' fondness for giants (vii). And so, in his Book of Giants** (1922), he makes a list of giants in almost all mythologies around the world. However, these myths also had to account for the disappearance of these extraordinary human beings. Like many origin or creation myths, the myth of the origin of the Logone river linked the disappearance or rarity of giants to early humanity’s rebellion against God.

In this community, this myth with its many variants always maintains the bone structure of man’s fall from God’s grace and the subsequent loss of former privileges. Traders and petty traders often use such myths to beguile their long hours of hard work which sometimes entail walking from village to village to sell their goods and having to spend the night away from home. However, they are always told to children and young adults at home to teach them about their origins and to impart societal values.

* Scholte et al explain the source of the importance of the Logone river to the inhabitants of the Lake Chad Basin. Its floodplains provide pastures and water for thousands of shepherds and farmers, some of whom migrate there to live for a period in Cameroon, Niger, Nigeria and Chad.

** Henry Wysham Lanier, A Book of Giants. New York: E. P. Dutton and Company, 1922.

Further Reading

Achebe, Chinua, Arrow of God, New York: Anchor Books, 1989.

Lanier, Wysham Henry, A Book of Giants, New York: E. P. Dutton and Company, 1922.

Murtagh, Lindsey, “Common Elements in Creation Myths”, cs.williams.edu (accessed: March 16, 2020).

Scholte, Paul, Saïdou Kari, Mark Moritz and Herbert Prins, “Pastoralist Responses to Floodplain Rehabilitation in North Cameroon”, Human Ecology 34 (2006): 27–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-005-9001-1. 22 April 2016 (accessed: March 16, 2020).

Addenda

Method of data collection: Note taking

Researchers: Didymus Tsangue Douanla and Aïcha Saïd Larissa

Research Assistant: Seïd Houzibe (trans. into French)

Editor: Daniel A. Nkemleke (trans. into English)