Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Nathaniel Hawthorne, A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys. Boston: Ticknor, Reed and Fields, 1852, (number of pages unknown).

ISBN

Available Onllne

gutenberg.org (accessed: August 2, 2018).

Library of Congress (accessed: December 15, 2021).

Genre

Didactic fiction

Illustrated works

Myths

Short stories

Target Audience

Children

Cover

Cover of the 1893 edition. Public domain. Available at Archive.org (accessed: March 12, 2022).

Cover of the edition of the University Publishing Company from 1896. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, public domain (accessed: December 15, 2021).

Author of the Entry:

Miriam Riverlea, University of New England, mriverlea@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaounde 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

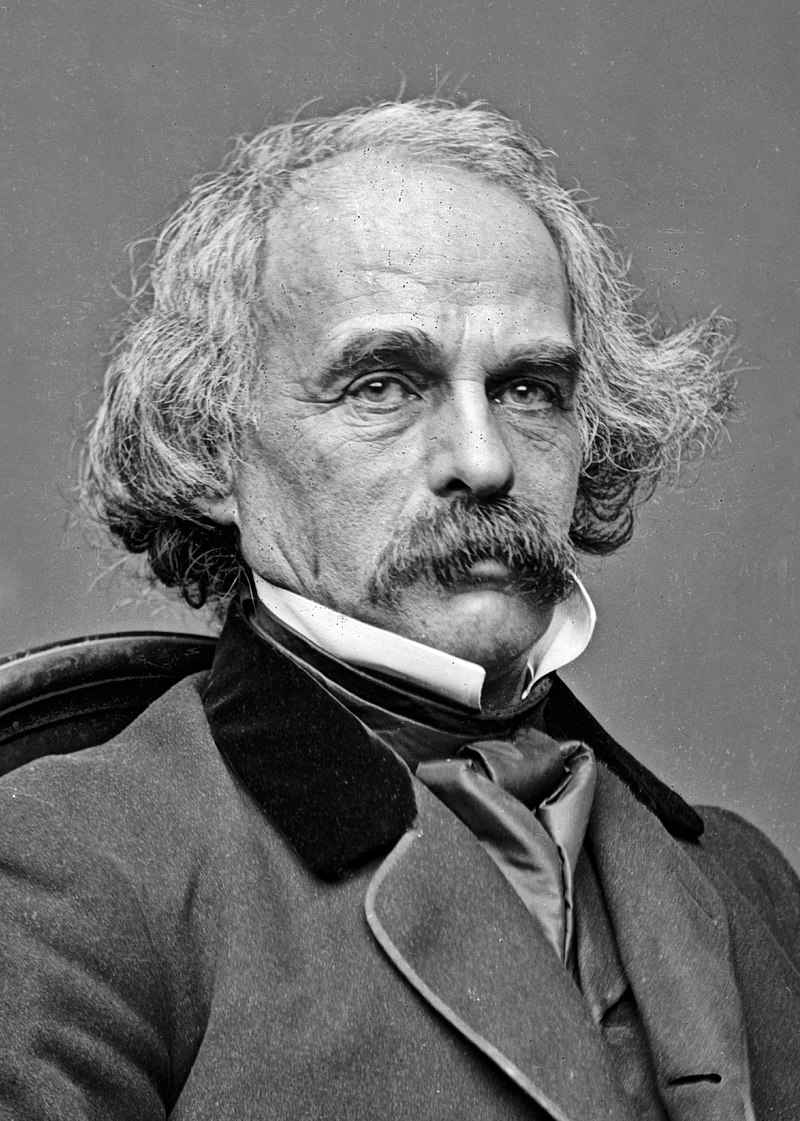

Retrieved from Wikipedia Commons, public domain (accessed: December 8, 2021).

Nathaniel Hawthorne

, 1804 - 1864

Nathaniel Hawthorne was born in Salem, Massachusetts, on July 4th, 1804, into a well-established Puritan family. One of his ancestors, John Hathorne, was a judge during the Salem Witch Trials of the 1690s. Although Nathaniel added the ‘w’ to his surname to distance himself from this branch of the family, his Puritan heritage had a deep influence on his writing. His best-known novels The Scarlet Letter (1850) and The House of the Seven Gables (1851) explore the themes of guilt and repentance, sin and retribution, and are widely regarded as classics of American literature.

Hawthorne’s ambition to be a writer was established during childhood, when a leg injury kept him bedridden for several months, with books as his only source of entertainment. His father, a sea captain, died of yellow fever when Nathaniel was four, and the family was taken in by his mother’s wealthy brothers, who went on to support his studies. After completing university Hawthorne began self-publishing short stories, including Twice Told Tales (1837) and in 1841, Grandfather’s Chair, a history of New England written for children. In 1842 he married Sophia Peabody, an artist with an interest in transcendentalism, and they went on to have three children.

A Wonder Book for Girls and Boys (1851) and its sequel, Tanglewood Tales (1853), were written during Hawthorne’s most productive period, following the financial and critical success of his novels. In the Preface to A Wonder Book, Hawthorne describes the experience of writing the book as “a pleasant task…and one of the most agreeable, of a literary kind, which he ever undertook.” In later life his writing became disordered, and after an extended illness he died in his sleep on May 19, 1864.

Bio prepared by Miriam Riverlea, University of New England, mriverlea@gmail.com

Adaptations

Chris King’s Monsters of the Greek Myths (1989) – a film (?) based on Hawthorne’s text as an educational resource for school students. Created by Spoke Arts in St. Petersburg, Florida. (Referenced in Worldcat)

The gorgon's head: a one-act opera by Samuel Magrill, Kay Creed; Carveth Oosterhaus, University of Central Oklahoma, 1998.

Numerous audiobook versions, most recently from 2010 by Bobbie Frohman and David Thorn, published by Alcazar AudioWorks, California.

Translation

Multiple languages

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

Hawthorne published a sequel, Tanglewood Tales in 1853.

Summary

First published in 1851, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s A Wonder Book for Girls and Boys holds a significant place in the reception of classical myth as one of the first retellings written in English specifically for children (Charles Lamb’s Adventures of Ulysses, published in 1808, is an important predecessor, and Charles Kinglsey’s The Heroes, or, Greek Fairy Tales for My Children, was published five years later in 1856). Prior to this, mythic stories predominantly featured in the context of classical dictionaries and language primers. According to Sheila Murnaghan and Deborah H. Roberts, Hawthorne ‘revolutionised the treatment of myth for children by presenting it as entertainment rather than a source of information.’ (13) While drawing extensively upon scholarly sources, particularly Charles Anthon’s Classical Dictionary, Hawthorne lightens the tone and tenor of the mythic material to heighten its appeal to a young audience. Prior to commencing the project, he outlined his intentions in a letter to his publisher James Thomas Fields, to imbue the myths with a Romantic or Gothic tone, purging them of their ‘classic coldness, which is repellent as the touch of marble’ and to ‘put in a moral wherever practicable.’ (Murnaghan and Roberts, 23)

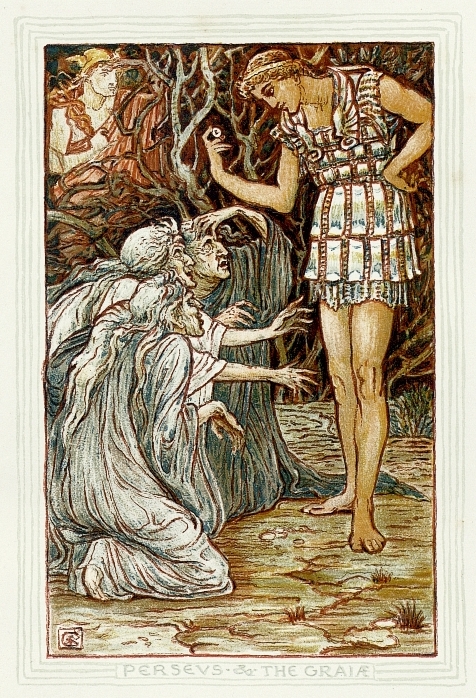

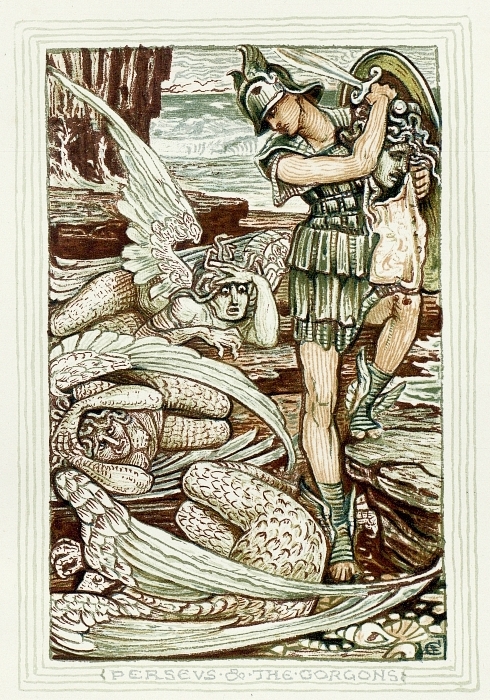

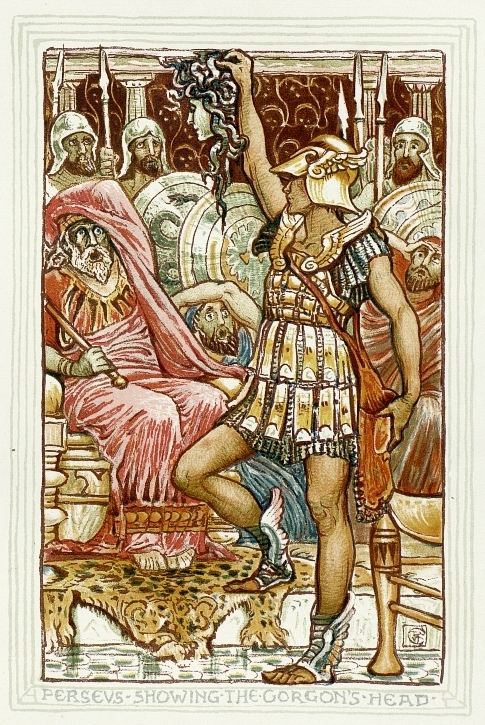

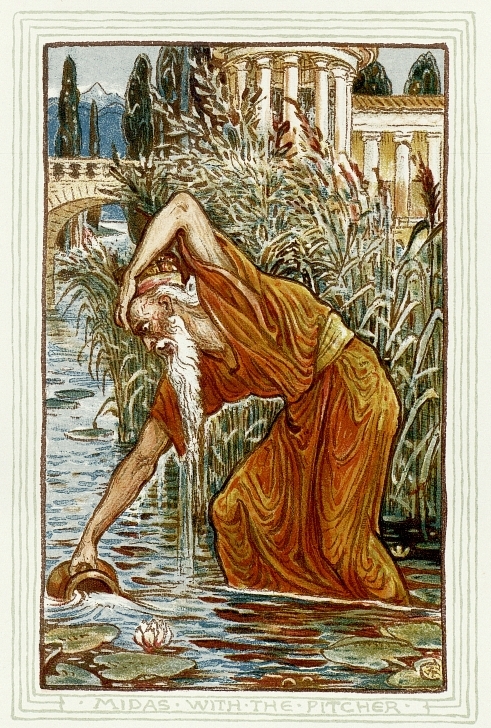

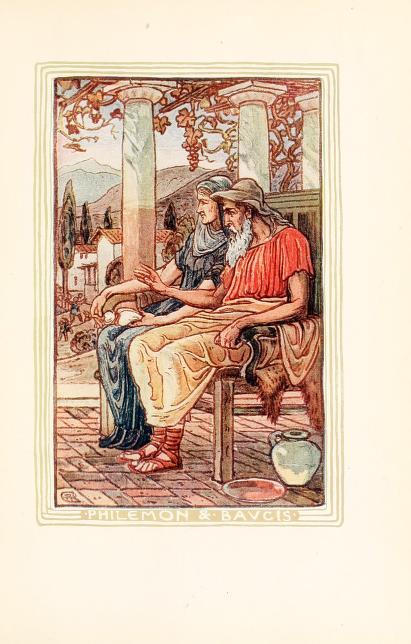

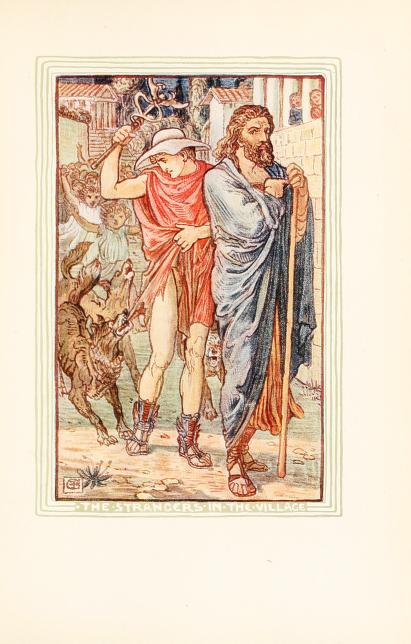

A Wonder Book contains retellings of six classical myths: The Gorgon’s Head (Perseus and Medusa), The Golden Touch (King Midas), The Paradise of Children (Pandora), The Three Golden Apples (Heracles’ labour to retrieve the golden apples from the Garden of the Hesperides), The Miraculous Pitcher (Baucis and Philemon), and The Chimaera (Bellerophon). The stories are tied together by a contemporary frame narrative set at Tanglewood, a grand estate in Lenox, Massachusetts, where Hawthorne lived for a time. Their narrator is Eustace Bright, a precocious, bespectacled 18-year-old student from Williams College, who is visiting the manor, and acts as a mouthpiece for Hawthorne himself, justifying his adaptations and revisions in self-conscious moments of metafiction.

Eustace’s audience is a gaggle of young cousins and their friends, whose floral aliases (such as Primrose, Periwinkle, Buttercup), echo the names of fairies from A Midsummer Night’s Dream (3). Having exhausted his supply of fairy tales on previous visits, Eustace turns to the corpus of myth for inspiration. As the seasons shift over the course of the year, he repeatedly returns to Tanglewood to tell his stories. With a cast of stock characters and moments of magic, his versions closely resemble fairy tales.

Each tale is framed by an introduction detailing the setting, either inside of the Manor house or its natural surroundings, which Eustace links directly to his chosen tale. Pandora’s tale is told by the fireside during a snowstorm, while the story of Pegasus is performed on a mountaintop.Afterwards, a brief ‘After the Story’ section consolidates its moral lesson and records the feedback and responses of the children. As Murnaghan and Roberts point out, this context reflects the oral performance traditions of antiquity.

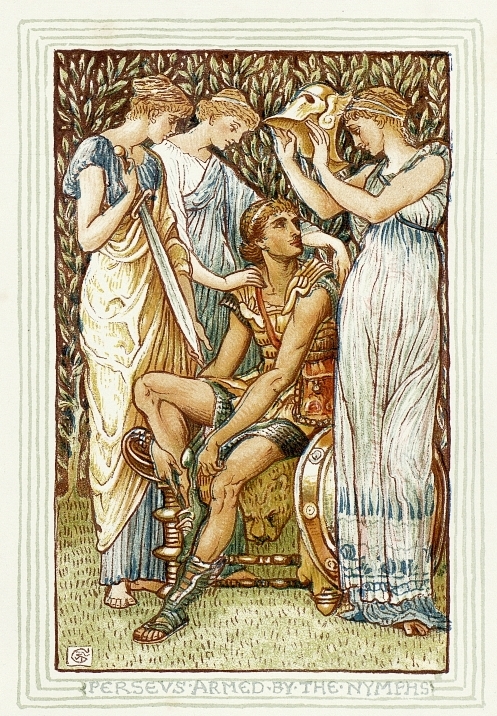

Early editions of the text included illustrations by the English artist Walter Crane, a prolific and influential children’s illustrator of the late nineteenth century and member of the Arts and Crafts movement. The woodcut headings imply the rustic, folktale origins of the stories, while the paintings emphasise the physical beauty of the gods and heroes and invoke the drama of their encounters. The intricate layering of foliage and other decorative elements is aesthetically appealing and helps to consolidate the position of this work in the canon of early children’s literature.

Analysis

The influence of A Wonder Book for Boys and Girls on recent retellings and adaptations is momentous, although not often acknowledged directly. A number of retellings, including Saviour Pirotta and Jan Lewis’ The Orchard Book of First Greek Myths (2003), follow Hawthorne’s storylines closely. Sally Grindley and Nilesh Mistry’s Pandora and the Mystery Box (1999) follows Hawthorne in featuring Quicksilver as an appellation of Hermes, while Kathryn Hewitt’s King Midas and the Golden Touch (1988) uniquely features a portrait of Hawthorne on its dedication page.

Like many more recent storytellers, Hawthorne struggles with the elements of the myths that he deems not acceptable for a young audience. In planning the volume, he declared his intention to ‘purge out all the old heathen wickedness’ from the stories, and glosses over references to sex and other forms of immoral behaviour. (Murnaghan and Roberts, 23)

The concept of childhood plays a prominent and critical part in A Wonder Book. Drawing on the ideals of the Romantic era, Hawthorne links childhood with notions of innocence and connections to the natural world. He suggests that the young have a special affinity with myth, based on the idea that the myths originate from a time when the world itself was young. In the introduction to the first tale, Eustace declares to his audience ‘I will tell you one of the nursery tales that were made for the amusement of our great old grandmother, the Earth, when she was a child in frock and pinafore.’ (6)

Child characters feature prominently in the stories. When Bellerophon is searching for Pegasus, the adults he consults doubt the horse’s existence, but a little boy maintains that he saw the creature only yesterday. The story promotes the notion of the young having a special affinity with the realm of myth that abates with maturity. Similarly, the title given to this version of the myth of Pandora, ‘The Paradise of Children’, underscores the connection in its description of an idyllic world in which there is no sickness or death, where ‘everybody was a child.’ (76) Pandora and her playmate Epimetheus are cast as naughty children, who in opening the forbidden box bring this epoch to a close. Troubles are released into the world, and for the first time, its inhabitants begin to grow older.

In addition to infantilising established characters of myth, Hawthorne invents his own. He gives King Midas a daughter, Marygold, who, according to Eustace, ‘nobody but myself ever heard of.’ (46) Midas’ folly in desiring the golden touch reaches a tragic climax when he inadvertently transforms his daughter into a golden statue. Although she does not figure in Ovid’s retelling or any other ancient source, the figure of Marygold is so compelling that she appears in numerous retellings of the Midas myth written for children, and has even been given a chance to tell her own story in Annie Sullivan’s young adult novel A Touch of Gold (2018).

As Hawthorne anticipated, A Wonder Book was a commercial success, selling significantly more copies than many of his novels for adults. Though rarely read by children in the English speaking countries today, the book, along with its sequel, Tanglewood Tales (1853), retains a significant place in the corpus of children’s retellings of classical myth and continues to exert an influence on the tradition.

Myth of Perseus, Midas, Philemon and Baucis. Illustrations by Walter Crane – these images are copyright free and in the public domain anywhere that extends copyrights 70 years after death or at least 120 years after publication when the original illustrator is unknown.

Further Reading

Donovan, Ellen Butler, “‘Very capital reading for children’: reading as play in Hawthorne’s A Wonder Book for Girls and Boys”, Children’s Literature 30 (2002): 19–41.

Laffrado, Laura, “Hawthorne 2.0”, Nathaniel Hawthorne Review 36.1 (2010): 28.

Laffrado, Laura, Hawthorne's Literature for Children, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1992.

McPherson, Hugo, Hawthorne as Myth-Maker: A Study in Imagination, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1969.

Murnaghan, Sheila, “Classics for Cool Kids: Popular and Unpopular Versions of Antiquity for Children” in Classical World 104.3 (2011): 339–353.

Murnaghan, Sheila and Deborah H. Roberts, Childhood and the Classics: Britain and America 1850 – 1965, Classical Presences Series, Oxford: University of Oxford Press, 2018.

Schein, Seth, “Greek Mythology in the works of Thomas Bulfinch and Gustav Schwab”, in Classical Bulletin, 84.1 (2008): 74–80.

Addenda

Recent edition: Nathaniel Hawthorne, A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys, New York: Barnes and Noble, 2013, 216 pp.