Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

René Goscinny, ill. Albert Uderzo, Astérix gladiateur. Paris: Hachette Livre, 1964, 48 pp.

ISBN

Official Website

asterix.com (accessed: September 14, 2020).

Genre

Action and adventure comics

Comics (Graphic works)

Historical fiction

Humor

Illustrated works

Target Audience

Crossover (Children; Young adults)

Cover

We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover.

Author of the Entry:

Miriam Riverlea, University of New England, mriverlea@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

René Goscinny

, 1926 - 1977

(Author)

René Goscinny was born in 1926 in Paris. He was the son of Jewish immigrants to France from Poland. Born in Paris, he moved with his family to Buenos Aires, Argentina, at the age of two. In 1943 he was forced into work by his father’s death, eventually gaining work as an illustrator in an advertising firm. Living in New York by 1945, Goscinny was approaching the usual age of compulsory military service. However, rather than join the United States Army, he elected to return to his native France to complete its year-long period of service. Throughout 1946, Goscinny was with the 141st Alpine Infantry Battalion, and found an artistic outlet in the unit’s official and semi-official posters and comics. His first commissioned illustrated work followed in 1947, but he then entered into a period of hardship upon moving back to New York City. Some important networking occurred thereafter with other emerging comic artists, before Goscinny returned to France in 1951 to work at the World Press Agency. There, he met lifelong collaborator, Albert Uderzo, with whom he co-founded the Édipresse/Édifrance syndicate and began publishing original material.

As Edipresse/Edifrance developed, Goscinny continued to work across a number of publications in the 1950s, including Tintin magazine from 1956. A key output from this period was a collaboration with Maurice De Bevere (1923–2001). They created together series of comics: about Lucky Luke (with Maurice), and about Asterix (with Uderzo). Goscinny worked with Jean Jacques Sempe and they created a series about boy called Nicolas.

The following year (1959), the syndicate launched its own magazine, Pilote; and the first issue contained the earliest adventure of ‘Astérix, the Gaul’, scripted by Goscinny himself, and drawn by Uderzo. On the back of Astérix, Pilote was a huge success, but managing a magazine was a challenge for the members of the syndicate. Georges Dargaud (1911–1990) – publisher of Tintin, and a major force in Franco-Belgian comics – saw the opportunity to purchase Pilote in 1960, and put it on a firmer footing, financially. Already the leading script-writer on the magazine, Goscinny was co-editor-in-chief of Pilote from 1960. Such was its success that by 1962, he was able to leave Tintin magazine in to edit Pilote full-time, and he held that role until 1973.

Goscinny’s success with Astérix and Lucky Luke (published in serialized instalments in the magazine, as well as in album-form by Dargaud) saw him enjoy a comfortable life, but this arguably contributed to his growing ill-health. He had married in 1967 – to Gilberte Pollaro-Millo – and a daughter – Anne Goscinny – was born the following year, as he continued to work with Uderzo and others. Pilote and Astérix were sufficiently profitable to be a full-time job, and twenty-three Astérix adventures were completed by 1977, when Goscinny died suddenly of a cardiac arrest during a routine stress test. Uderzo completed the story Astérix chez les Belges [Asterix in Belgium] and continued the series alone.

Goscinny was not only a comic book author but also a director and co–director of animated movies (Daisy Town, Asterix and Cleopatra), feature movies (Les Gaspards, Le Viager). Goscinny. He died in 1977 in Paris.

Sources:

bookreports.info (accessed: September 14, 2018)

britannica.com (accessed: September 14, 2018)

lambiek.net (accessed: September 14, 2018)

Bio prepared by Agnieszka Maciejewska, University of Warsaw, agnieszka.maciejewska@student.uw.edu.pl and Richard Scully, University of New England, Armidale rscully@une.edu.au

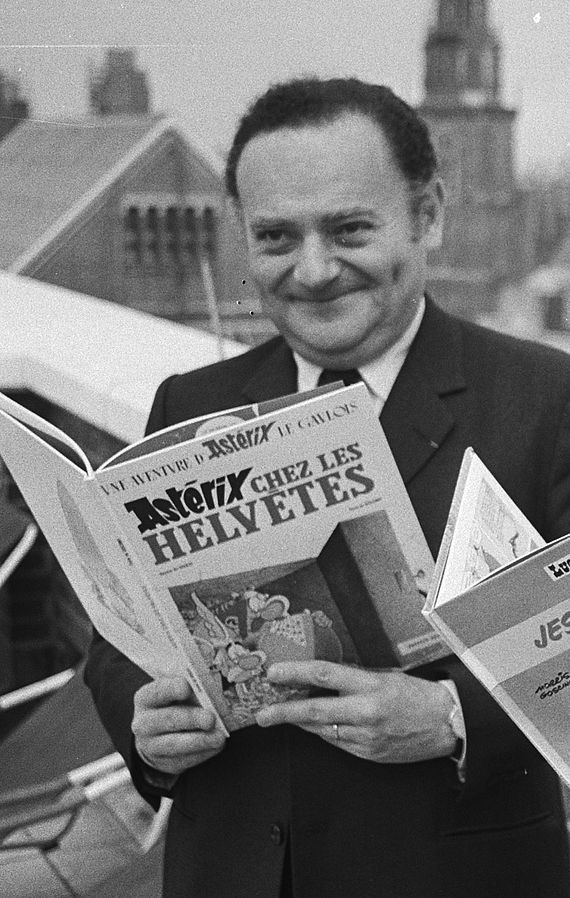

Albert Uderzo in 1973 by Gilles Desjardins. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 (accessed: December 30, 2021).

Albert Uderzo

, 1927 - 2020

(Illustrator)

Albert Uderzo was born in Fismes, France, in 1927. The son of Italian immigrants, he experienced discrimination following the family’s move to Paris, at a time when Fascist Italy was pursuing an aggressive course, internationally (on top of the usual xenophobia directed at immigrants). Uderzo came into contact with American-imported comics around the late 1930s (including Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck). He also discovered that he was colour-blind (despite art being the only successful aspect of his schooling career). Living in German-occupied France, from 1940, Uderzo tried his hand at aircraft engineering, but illustration was where he found his métier. Post-war, he came into contact with the circles of Belgian-French comics artists; as well as meeting and marrying Ada Milani in 1953 (who gave birth to a daughter, Sylvie Uderzo in 1953).

He started his career as an illustrator after World War II. In 1951, he met René Goscinny at the World Press Agency. Together, they worked on a comic: ‘Oumpah-pah le Peau-Rouge’ [Ompa-pa the Redskin] – drawn by Uderzo and written by Goscinny. In 1959 Uderzo and Goscinny were editors of Pilote magazine. They published there their first Asterix episode which became one of the most famous comic stories in history. Individual albums of Astérix adventures appeared regularly from 1961 (published by Georges Dargaud following the completion of the serialized run in Pilote), and there were 23 completed adventures by the time Goscinny died in mid-1977. After Goscinny’s death, Uderzo took over the writing and continued publishing Asterix adventures, and completed 11 further albums by retirement in 2011 (including several that were compendiums of older material, co-created by Goscinny). In the late 2000s and early 2010s, Uderzo experienced considerable family disquiet; largely over the financial benefits expected to accrue to his daughter. Although maintaining for much of his career that Astérix would end with his death, he agreed to sell his interest in the character to Hachette Livre, who has continued the series since 2011, owing to the talents of Jean-Yves Ferri and Didier Conrad.

All stories about Asterix published till now are very successful and widely known. They are highly popular not only in France but have been translated into one hundred and ten languages and dialects. The series continues and Asterix (Le papyrus de Cesar) became the number one bestseller in France in 2015 with 1,619,000 copies sold. The sales figures and popularity of Asterix series are comparable with the Harry Potter phenomenon. Astérix et la Transitalique published in “2017 placed 76 among the French Amazon best sellers three weeks before it was published Among comic books for adolescents the title was number one, among comic books of all categories it was number two.”*

Albert Uderzo died on 24 March 2020.

Sources:

lambiek.net (accessed September 14, 2018).

Bio prepared by Agnieszka Maciejewska, University of Warsaw, agnieszka.maciejewska@student.uw.edu.pl and Richard Scully, University of New England, Armidale rscully@une.edu.au

*See Elżbieta Olechowska, “New Mythological Hybrids Are Born in Bande Dessinée: Greek Myths as Seen by Joann Sfar and Christophe Blain” in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Chasing Mythical Beasts…The Reception of Creatures from Graeco-Roman Mythology in Children’s & Young Adults’ Culture as a Transformation Marker, forthcoming.

Translation

English: Asterix the Gladiator, trans. Anthea Bell and Derek Hockridge, Leicester: Brockhampton Press, 1969, 48 pp.

German: Asterix als Gladiator, trans. Gudrun Penndorf, Adolf Kabatek and Wolf Stegmaier, Berlin, Köln: Egmont, 2015.

Polish: Asteriks gladiator, trans. Jarosław Kilian, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Egmont Polska, 2011.

Dutch: Asterix als Gladiator, Brussel De Lombard Uitgaven, 1968.

Russian: Астерикс-гладиатор [Asteriks-gladiator], trans. Michail Chatjatorov, Moskva: Machaon, 2017.

Bengali: Glyāḍiyéṭara Ayāsṭeriksa, Kalakātā: Ananda Pābaliśārsa, 1997.

Summary

The fourth installment in the Astérix series begins with the Prefect of Gaul, Caligula Alavacomgetepus (Odius Asparagus in English), visiting Petibonum (Compendium in English), one of the Roman camps near the Gaulish village that is home to Astérix and Obélix. He hopes to curry favour with Julius Caesar by bringing him one of the Gauls as a present, but Centurion Gracchus Nenjetépus (n'en jetez plus, Gracchus Armisurplus in English) is well aware that the Gauls are formidable fighters. Nevertheless, his soldiers manage to capture the bard Assurancetourix (assurance tous risques, Cacofonix in English), protecting themselves from his discordant singing by stuffing parsley in their ears. A small boy who witnesses his abduction alerts Astérix and Obélix, and they lead the Gauls in a brutal attack on Petibonum, but discover that Assurancetourix has already been taken to Rome on the Prefect’s galley. Astérix and Obélix hitch a ride on a Phoenician merchant ship, captained by the mercantile Epidemaïs (épi de maïs, Ekonomikrisis in English), who insists that his hardworking oarsmen are not slaves, but business partners who failed to read the fine print of the contract before they signed. The ship is attacked by pirates, who are quickly and brutally dispatched by the two Gauls. Epidemaïs is greatly relieved, and delivers his new friends safely to Rome.

Bound in chains, Assurancetourix is presented to Julius Caesar, who commands him to be thrown to the lions at the next games. Astérix and Obélix arrive in Rome and meet a fellow Gaul, the restaurant proprietor Plaintcontrix (plainte contre X, Instantmix in English). They visit the Baths, inadvertently causing havoc with their uncouth and violent ways. Caius Obtus (Caius Fatuous in English), a Gladiator Trainer, is impressed by their strength and vows to draft them. But his men are brutally defeated by Astérix and Obélix, who delight in the fight as they visit Instantmix in his apartment and secure accommodation for the night. They discover that Assurancetourix is being held in a cell below the Circus, but when they sneak in to rescue him (dispatching sentries along the way), they learn that he has been moved to the third basement as no one can bear to listen his appalling singing any more. Still determined to make the Gauls into gladiators, Caius Obtus offers a reward of ten thousand sesterii for their capture. Astérix and Obélix blithely repel all attacks, as Astérix independently decides that the best way to rescue Assurancetourix is to become gladiators. Obtus is alarmed when they return to the baths to find him, but recovers and takes them home for a lavish, exotic meal, which Obélix greedily devours.

The brutish Briseradius (brise radius, Insalubrius in English) is put in charge of their training. Obélix is frustrated by Briseradius’ ability to dodge and fails to land a punch, but Astérix quickly lands a powerful uppercut. When he recovers he declares that Obélix will be a retiarius, armed like a fisherman with a net and a stick. Rejecting the stick, Obélix demonstrates how he catches a fish with his bare hands, before ensnaring the furious Briseradius in the net. After the trainer storms off to complain, Astérix invites the other gladiators to play word games. As the program for the Grand Circus Games is promoted throughout the city, Astérix and Obélix escape the Gladiators’ quarters and pressure Obtus into take them on a tour of the city. Terrified by Caesar’s threat that he will be fed to the lions if the people are not satisfied with the entertainment, Obtus conceals his frustration with his blasé companions.

The games begin with a chariot race. One of the drivers is too drunk to drive and Astérix and Obélix volunteer in his place. Astérix’s driving skills and Obélix’s strength ensure they destroy their opponents and win the race with ease, to the delight of the crowd and Caesar himself. In the next act Assurancetourix is led out to be fed to the lions. After casually greeting Caesar "Hi, Julius!" he seizes the opportunity to perform for the huge crowd, appalling the audience and causing the lions to run away like terrified kittens. Finally, the gladiators begin their display. While the rest of the group acknowledge Caesar in the formal manner: "Ave Caesar! Morituri te salutant!" Astérix and Obélix enrage him by saying "Hi, Julius, old boy!" (p. 50). The dictator grows ever more furious as Astérix encourages the other gladiators to throw down their weapons and play word games. Caesar commands his best legionaries to enter the arena as Astérix downs the last of his magic potion. The Gauls thoroughly trounce their opponents, and Caesar consents to their requests to free Assurancetourix and the other gladiators. The unfortunate Caius Obtus escorts them back to Gaul, singlehandedly rowing the Phoenician galley before returning to Rome. After another skirmish with the pirates, Astérix and Obélix return to their village, where the Gauls celebrate with a feast. Assurancetourix, bound and gagged, looks on from his treehouse.

Analysis

Full of puns and wisecracks, slapstick and stereotypes, Asterix the Gladiator is a plot heavy, rollicking romp. Its two heroes are an appealing pair who, despite their occasional arguments, work exceedingly well in partnership. Asterix is small and smart, while his best friend Obelix is huge in stature, strength and appetite. His hedonistic personality is embodied in his obsession with wild boar. Asterix’ superlative fighting prowess derives from the magic potion brewed by the local druid (unnamed in this book); Obelix attempts to sample some but is turned away. While the infamous story of his accidental immersion in the potion as a baby is not mentioned in this book, Obelix uses his catch-phrase "These Romans are crazy!"* for the first time.

This is an intensely masculine narrative (the book contains no female characters). The fight scenes are frequent and farcical, with the Gauls so superior to their Roman opponents that at times Asterix and Obelix dispatch them without breaking stride or pausing their conversation. The violence is constant yet untroubling. The reader derives a carnivalesque pleasure to see the might of the Romans so easily overcome by two humble Gauls. In addition, Asterix the Gladiator depicts the cultural practices and institutions of Republican Rome, showcasing rituals of dining, bathing and entertainment. Famous landmarks and buildings appear throughout the illustrations. As the Gauls tour the Roman forum, they see Egyptians, Greeks and other tourists taking in the sights and buying souvenirs. Soon after, a Roman sentry tells off an Egyptian for carving hieroglyph graffiti onto a column.

Resplendent in toga and laurel wreath, and with a gaunt face dominated by an aquiline nose, Julius Caesar is a formidable figure. While the Romans cower and cringe in his presence, the Gauls pay no heed to his status, addressing him by his first name. While their antics in the arena infuriate him, Caesar acknowledges their bravery, and they part on respectful terms, united in their pleasure at seeing Caius Obtus (Caius Fatuous) brought low. Brutus appears as a drowsy dope sitting alongside Caesar at the circus. After being forcefully reminded to join in the applause ("Et Tu Brute!"), Caesar prophetically thinks that he will have trouble with him.

The book engages with issues of power and status, subtly incorporating ideologies from our own time in the pursuit of a happy ending. With Caesar’s blessing, Asterix liberates the gladiators from a life of bloodthirsty servitude, and punishes their trainer for doing "a dirty job and [living] off other people’s muscle" (p. 55). Other anachronisms are purely humorous. Many of Assurancetourix (Cacofonix)’ unbearable songs are riffs on modern compositions, including Menhir montant, parody of Ménilmontant by Charles Trénet ("Love is a Menhir Splendid Thing" in English) (p. 37) and Jolie fleur de patricien, parody of Jolie fleur de papillon by Annie Cordy ("For Gau-Aul Lang Syne my Dears…" in English) (p. 41).

It isn’t necessary to get every joke or reference to enjoy Asterix. More than fifty years since its release, the series continues to entertain young readers. While they may learn something about the Roman world along the way, the series’ inaccuracies and irreverence make the lessons more playful than precise.

* « Ils sont fous, ces Romains ! »

Further Reading

Kessler, Peter, The Complete Guide to Asterix, London: Hodder, 1995.