Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Edmund Niziurski, Sposób na Alcybiadesa, ill. by Zbigniew Łoskot. Warszawa: Nasza Księgarnia, 1964, 261 pp.

ISBN

Awards

1978 – IBBY Honour List

Genre

School story*

Target Audience

Crossover (Children, teenagers (9–17 years))

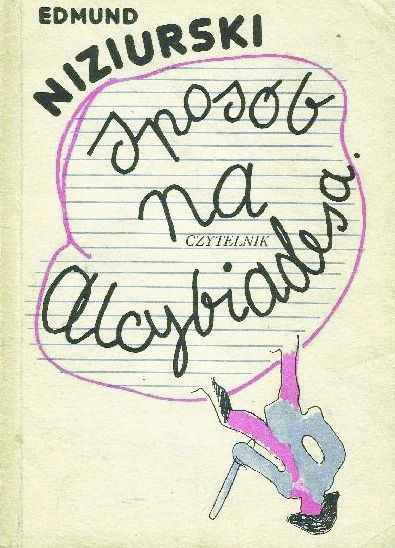

Cover

Cover from the edition Warsaw: Czytelnik, 1987. Cover design and illustrations by Zbigniew Czarnecki.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Paulina Kłóś, University of Warsaw, paulina.klos@student.uw.edu.pl

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

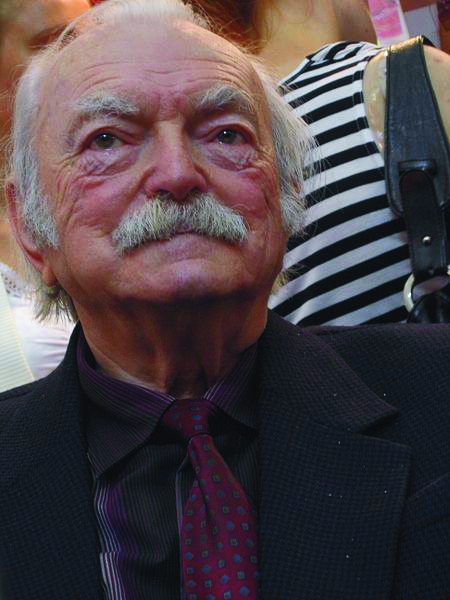

Photograph by Mariusz Kubik, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons (accessed: December 28, 2020).

Edmund Niziurski

, 1925 - 2013

(Author)

A prose writer, playwright and scriptwriter, literary critic. Born in Kielce; WW2 interrupted his high school education; spent the first year of the war in Hungary. Finished his high school in Poland in 1943 (underground courses). He debuted in 1944 with a poem published in the “Information Bulletin” of Armia Krajowa [Home Army]. Studied law at the Catholic University in Lublin, then law and sociology at the Jagiellonian University in Cracow. Member of the Union of Polish Writers since 1952. Received many awards: e.g. Order of the Smile (an international award given by children for pro-children activities), and Gloria Artis Medal for Merit for Culture (Gold Class). Known and appreciated for a distinctive sense of humour and irony. Author of radio-plays for children, film and television scripts. Sposób na Alcybiadesa [How to Get Alcibiades], 1964, and Niewiarygodne przygody Marka Piegusa [Unbelievable Adventures of Marek Piegus], 1970, are the most popular among his many novels for young readers. Sposób na Alcybiadesa made IBBY Honour List in 1978.

Sources:

Kątny, Marek and Jan Pacławski, Edmund Niziurski. Materiały z sesji w 70 rocznicę urodzin, Kielce: Wyższa Szkoła Pedagogiczna im. Jana Kochanowskiego, Kieleckie Towarzystwo Naukowe, 1996.

Jadach, Jan and Anna Łojek, "Edmund Niziurski. Bibliografia podmiotowo-przedmiotowa", in Marek Kątny and Jan Pacławski, O twórczości Edmunda Niziurskiego, Kielce: Kieleckie Towarzystwo Naukowe, 2005, 177–218.

"Nizurski Edmund", in Leszek M. Bartelski, Polscy pisarze współcześni 1939– 1991. Leksykon, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1995, 289.

Edmund Niziurski, ksiazki.wp.pl (accessed: December 28, 2020).

Edmund Niziurski, pl.wikipedia.org (accessed: December 28, 2020).

Bio prepared by Paulina Kłóś, University of Warsaw, paulina.klos@student.uw.edu.pl

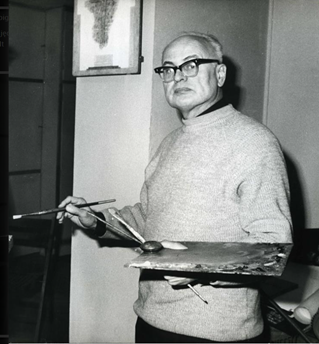

Photograph courtesy of Jacek Łoskot, the Artist's Son.

Zbigniew Łoskot

, 1922 - 1997

(Illustrator)

Zbigniew Łoskot (1922–1997) was a Polish painter, illustrator, printmaker and graphic designer. He was born in Warsaw, where he passed his high school final exam in clandestine courses during the Nazi occupation in 1942. He cooperated with the magazine Sztuka i Naród [Art and Nation]. He graduated from the Faculty of Painting at the Akademia Sztuk Pięknych im. Jana Matejki (Jan Matejko Academy of Fine Arts) in Cracow in 1949 (he finalized his degree in 1954). He was active in various areas and techniques of art, such as monumental wall painting, frescoes, sgraffito, mosaics, stained glass, easel painting (oil, tempera), woodcut, linocut or drypoint. He was well known for his sacred art – he designed and decorated many churches and chapels rebuilt and built after WW2, including the Primate’s of Poland chapel in the Warsaw Metropolitan Cathedral, all together, ten chapels and over twenty churches.

As an illustrator, he cooperated with many publishers, including Pallotinum, where he designed the cover and jacket of the Millennium Bible – the most famous 20th-cent. Polish edition of the Bible. Among other publishing houses, he worked for were also Iskry, KAW, PAX and Nasza Księgarnia, where he illustrated mainly books for children. He exhibited multiple times in Poland and abroad in individual or group shows. His works are held by the Vatican Museums, various Polish museums, Éditions du Dialogue founded in Paris by Polish Pallottines in 1966, and Pallottine collections in Rome.

In 1972, Nasza Księgarnia published Kolorowy świat – ilustracje w książkach „Naszej Księgarni” 1921–71 [Coloured World – illustrations in books by „Nasza Księgarnia”] including also works by Zbigniew Łoskot with the child reader in mind.

Source:

Official website (accessed: February 25, 2022).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Adaptations

TV series (3 parts): Sposób na Alcybiadesa, dir. Waldemar Szarek, 1997.

Film: Spona, dir. Waldemar Szarek, Gutek Film, 1998.

Translation

Bulgarian: Sposob za Alkiviad, trans. Liliâ Račeva, Sofiâ: Otečestvo, 1976.

Czech: Jak vyzrát na Alkibiada, trans. Anetta Balajková, Praha: Albatros,1974.

Georgian: Rogor dawihsenith thawi–alkibadesagan: sam skolis mosnawdeha theis, trans. L. Leškašelma, Tbilisi: Nakaduli, 1973.

German: Verschwörung gegen Alkibiades, trans. Caesar Rymarowicz, Berlin: Der Kinderbuchverl., 1968.

Latvian: Līdzeklis pret Alkibiadu, trans. Voldemārs Meļinovskis, Rīgā: Liesma, 1972.

Russian: Sredstvo ot Alkiviada, trans. M. Bruhnova, Moskva: Detskaâ literature, 1967.

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

A group of schoolmates looked for a method of passing exams effortlessly. After many attempts, they succeeded in convincing an older boy (nick-named Shakespeare) to sell them a mysterious method that allows deceiving teachers. The sum of money that the boys collected was sufficient for dealing with only one teacher: the main character Alcibiades – an inconspicuous, elderly history teacher. The nick-name, perversely given to him by pupils, did not meet with his approval as he hated the Athenian leader. Having applied Shakespeare’s solution, boys believed that they were avoiding learning history, but what happened was the opposite. Alcibiades, aware of the scheme, controlled the situation. The young conspirators fooled by a sense of their own cleverness ended up as knowledgeable city tour guides.

Analysis

The action, set in the school year 1960/61, shows protagonists, 15-year-old boys, against the background of a traditional single-sex school in Warsaw. As they are not very diligent students, the main characters have problems with their teachers. When the headmaster calls them to his office, they have to listen to his lecture about being black sheep and disrespecting the proud school traditions. The incident is witnessed by a marble bust of Cato on a pedestal, a noble man of antiquity, renowned for his virtues, and by a horse called Cicero standing outside the window. The sculpture falls down and breaks. It is taken by the history teacher nicknamed “Alcybiades,” to be repaired even though nobody likes the ugly and beat-up piece. The Cato bust returns put back together with glue; then it becomes the subject of an argument and discussion between “Alcybiades” and the headmaster, who considers Cato a reactionary figure, especially that his views about the treatment of slaves are well known. “Alcybiades” has a different opinion – he considers Cato a symbol of Roman virtues and his bust – a silent witness of war and other events connected with the history of the school. When the headmaster rejects the request to put it back in his office, the boys propose to place the bust in their classroom. In return, “Alcybiades” suggests a triumvirate – between him, them, and Cato, treating them then not as ordinary students, but as free truth seekers with whom he could exchange thoughts.

Alcibiades is the main ancient character mentioned in the novel. It is used as a nickname for an older history teacher, Mr. Misiak. At first, the boys do not know why the nickname is used, as the teacher is bald, wears big glasses, his posture is hunched, his clothes wrinkled, he is kind-hearted and in no way resembles the ancient Greek from the encyclopedic entry. The real Alcibiades was an ancient Athenian leader, a student of Socrates, gifted and clever but spoiled, thus banished and finally murdered. Such an image, however, does not completely match Misiak. The mystery is solved, when the teacher tells a student that Alcibiades’ fate awaits him because being a student is not enough to gain wisdom – just like Alcibiades who was Socrates’ student but remained reckless and morally corrupt. The boys maliciously nicknamed the teacher after a figure he disliked, even though he was kind and thoughtful. The teacher, however, somehow ends up attracting his students to his subject; learning history becomes their true passion and causes an interior change when they grasp the value of Misiak’s hermeneutical approach (shown by bringing up the example of Pythagoras and comparing him to a contemporary cashier who uses electronic technology).

Besides the historical characters of Cato and Alcibiades, there are more references to classical antiquity which is a source of interest for the teacher. Mythological characters are present in Polish expressions, and many classical references are naturally encountered Latin maxims. Julius Caesar’s commanding presence is evoked when “Alcybiades” requests silence with a gesture in his style, and in the “triumvirate” he plays Caesar’s role. The teacher starts calling the class 8a “my eighth legion”. He also alludes to Punic Wars by comparing the geography teacher Kalino to Hannibal in a skirt and using a paraphrase of Cato’s famous sentence: ceterum censeo Kalinam delendam esse. He is also quite satisfied when someone draws his caricature on a wall with the subtitle spiritus flat ubi vult*, which is his favourite Latin phrase. As a real lover of antiquity, he also does not react with interest when the boys, trying to change the subject, distract him with an absurd tale of a spontaneous combustion of pants cleaned with gasoline. He quips by saying that it cannot be compared to the burning of the Alexandrian Library. Another famous Latin phrase, quoted with high frequency by the father of the narrating protagonist is historia vitae magistra**.

Mythological references are also present in the novel and include: Achilles’ heel when the boys seek the weak spot of their teacher, a photograph of Orpheus as “Shakespeare” disguised in “ancient” garments for a theatrical role, Hercules’ strength, Odysseus’ cleverness, and Achilles’ courage as Misiak would like to disseminate these features to calm his frisky students, Deianira’s robe as an unproved historical object in opposition to the garter of the Countess of Salisbury, and Hermes called an ancient “minister of Olympian gods’ mails” by one of the students who tells the history of the royal mail.

* Spiritus ubi vult spirat, NT, Secundum Ioannem 3,8 (Vulgata).

** Cicero, De oratore, 2,9.

Further Reading

Głowacki, Jerzy, Nazewnictwo literackie w utworach Edmunda Niziurskiego, Gdańsk: Gdańskie Towarzystwo Naukowe, 1999.

Kątny, Marek and Jan Pacławski, Edmund Niziurski. Materiały z sesji w 70 rocznicę urodzin, Kielce: Wyższa Szkoła Pedagogiczna im. Jana Kochanowskiego, Kieleckie Towarzystwo Naukowe, 1996.

Tylicka, Barbara and Grzegorz Leszczyński, eds., Słownik literatury dziecięcej i młodzieżowej, Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 2003, 272.