Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

René Goscinny, Albert Uderzo, "Le Domaine des Dieux", Pilote 591 (1971).

ISBN

Genre

Comics (Graphic works)

Target Audience

Crossover (Children and Young Adults)

Cover

We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover.

Author of the Entry:

Lisa Dunbar Solas, OMC contributor, drlisasolas@ancientexplorer.com.au

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaoundé 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

René Goscinny

, 1926 - 1977

(Author)

René Goscinny was born in 1926 in Paris. He was the son of Jewish immigrants to France from Poland. Born in Paris, he moved with his family to Buenos Aires, Argentina, at the age of two. In 1943 he was forced into work by his father’s death, eventually gaining work as an illustrator in an advertising firm. Living in New York by 1945, Goscinny was approaching the usual age of compulsory military service. However, rather than join the United States Army, he elected to return to his native France to complete its year-long period of service. Throughout 1946, Goscinny was with the 141st Alpine Infantry Battalion, and found an artistic outlet in the unit’s official and semi-official posters and comics. His first commissioned illustrated work followed in 1947, but he then entered into a period of hardship upon moving back to New York City. Some important networking occurred thereafter with other emerging comic artists, before Goscinny returned to France in 1951 to work at the World Press Agency. There, he met lifelong collaborator, Albert Uderzo, with whom he co-founded the Édipresse/Édifrance syndicate and began publishing original material.

As Edipresse/Edifrance developed, Goscinny continued to work across a number of publications in the 1950s, including Tintin magazine from 1956. A key output from this period was a collaboration with Maurice De Bevere (1923–2001). They created together series of comics: about Lucky Luke (with Maurice), and about Asterix (with Uderzo). Goscinny worked with Jean Jacques Sempe and they created a series about boy called Nicolas.

The following year (1959), the syndicate launched its own magazine, Pilote; and the first issue contained the earliest adventure of ‘Astérix, the Gaul’, scripted by Goscinny himself, and drawn by Uderzo. On the back of Astérix, Pilote was a huge success, but managing a magazine was a challenge for the members of the syndicate. Georges Dargaud (1911–1990) – publisher of Tintin, and a major force in Franco-Belgian comics – saw the opportunity to purchase Pilote in 1960, and put it on a firmer footing, financially. Already the leading script-writer on the magazine, Goscinny was co-editor-in-chief of Pilote from 1960. Such was its success that by 1962, he was able to leave Tintin magazine in to edit Pilote full-time, and he held that role until 1973.

Goscinny’s success with Astérix and Lucky Luke (published in serialized instalments in the magazine, as well as in album-form by Dargaud) saw him enjoy a comfortable life, but this arguably contributed to his growing ill-health. He had married in 1967 – to Gilberte Pollaro-Millo – and a daughter – Anne Goscinny – was born the following year, as he continued to work with Uderzo and others. Pilote and Astérix were sufficiently profitable to be a full-time job, and twenty-three Astérix adventures were completed by 1977, when Goscinny died suddenly of a cardiac arrest during a routine stress test. Uderzo completed the story Astérix chez les Belges [Asterix in Belgium] and continued the series alone.

Goscinny was not only a comic book author but also a director and co–director of animated movies (Daisy Town, Asterix and Cleopatra), feature movies (Les Gaspards, Le Viager). Goscinny. He died in 1977 in Paris.

Sources:

bookreports.info (accessed: September 14, 2018)

britannica.com (accessed: September 14, 2018)

lambiek.net (accessed: September 14, 2018)

Bio prepared by Agnieszka Maciejewska, University of Warsaw, agnieszka.maciejewska@student.uw.edu.pl and Richard Scully, University of New England, Armidale rscully@une.edu.au

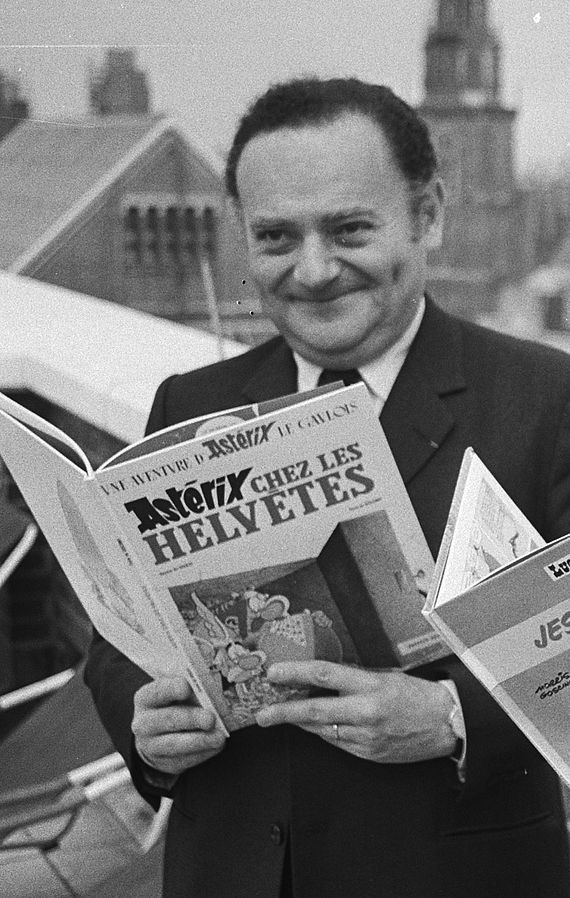

Albert Uderzo in 1973 by Gilles Desjardins. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 (accessed: December 30, 2021).

Albert Uderzo

, 1927 - 2020

(Illustrator)

Albert Uderzo was born in Fismes, France, in 1927. The son of Italian immigrants, he experienced discrimination following the family’s move to Paris, at a time when Fascist Italy was pursuing an aggressive course, internationally (on top of the usual xenophobia directed at immigrants). Uderzo came into contact with American-imported comics around the late 1930s (including Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck). He also discovered that he was colour-blind (despite art being the only successful aspect of his schooling career). Living in German-occupied France, from 1940, Uderzo tried his hand at aircraft engineering, but illustration was where he found his métier. Post-war, he came into contact with the circles of Belgian-French comics artists; as well as meeting and marrying Ada Milani in 1953 (who gave birth to a daughter, Sylvie Uderzo in 1953).

He started his career as an illustrator after World War II. In 1951, he met René Goscinny at the World Press Agency. Together, they worked on a comic: ‘Oumpah-pah le Peau-Rouge’ [Ompa-pa the Redskin] – drawn by Uderzo and written by Goscinny. In 1959 Uderzo and Goscinny were editors of Pilote magazine. They published there their first Asterix episode which became one of the most famous comic stories in history. Individual albums of Astérix adventures appeared regularly from 1961 (published by Georges Dargaud following the completion of the serialized run in Pilote), and there were 23 completed adventures by the time Goscinny died in mid-1977. After Goscinny’s death, Uderzo took over the writing and continued publishing Asterix adventures, and completed 11 further albums by retirement in 2011 (including several that were compendiums of older material, co-created by Goscinny). In the late 2000s and early 2010s, Uderzo experienced considerable family disquiet; largely over the financial benefits expected to accrue to his daughter. Although maintaining for much of his career that Astérix would end with his death, he agreed to sell his interest in the character to Hachette Livre, who has continued the series since 2011, owing to the talents of Jean-Yves Ferri and Didier Conrad.

All stories about Asterix published till now are very successful and widely known. They are highly popular not only in France but have been translated into one hundred and ten languages and dialects. The series continues and Asterix (Le papyrus de Cesar) became the number one bestseller in France in 2015 with 1,619,000 copies sold. The sales figures and popularity of Asterix series are comparable with the Harry Potter phenomenon. Astérix et la Transitalique published in “2017 placed 76 among the French Amazon best sellers three weeks before it was published Among comic books for adolescents the title was number one, among comic books of all categories it was number two.”*

Albert Uderzo died on 24 March 2020.

Sources:

lambiek.net (accessed September 14, 2018).

Bio prepared by Agnieszka Maciejewska, University of Warsaw, agnieszka.maciejewska@student.uw.edu.pl and Richard Scully, University of New England, Armidale rscully@une.edu.au

*See Elżbieta Olechowska, “New Mythological Hybrids Are Born in Bande Dessinée: Greek Myths as Seen by Joann Sfar and Christophe Blain” in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Chasing Mythical Beasts…The Reception of Creatures from Graeco-Roman Mythology in Children’s & Young Adults’ Culture as a Transformation Marker, forthcoming.

Translation

The Mansions of the Gods has been translated into 34 languages, see here (accessed: January 29, 2021).

Summary

The Mansions of the Gods is the 17th volume of the Astérix comic series. The main characters of this series are the clever and brave Gaul called Astérix and his strong sidekick, Obélix. In their adventures, which follow a similar character arc and plotline, they fight the invaders of the Gaul territory, the Romans. Together, Astérix and Obélix are helped by Panoramix (Getafix in English), who prepares a magical potion that gives them great strength and power.

In the present story, Julius Caesar plans on constructing a large holiday residential complex called “The Mansions of the Gods” next to a Gaulish village. In order to build the complex, he has to destroy a sacred grove. Caesar places the architect, Anglaigus (angle aigu, Squareonthehypotenus in English), in charge of the project and he commands an army of slaves to cut down all the trees of the grove. Upon discovering that the grove had been destroyed, Astérix and Obélix help the mature trees regenerate rapidly using Panoramix (Getafix)’s magic seeds. A dismayed Anglaigus (Squareonthehypotenus) orders the slaves to cut the trees down again. Then, Astérix and Obélix assist the grove to regenerate once more. This cycle continues until Squareonthehypotenus threatens "to work the slaves to death."

Upon hearing this threat, Astérix gives the slaves a potion. He hopes it will cause them to rebel. His plan is thwarted when the slaves, under the influence of the potion, demand better work conditions, including regular pay and freedom once the first block of the complex is completed. Once granted, the Roman legionaries then strike for similar rights and conditions. The Gauls allow the slaves to construct one building since their freedom is reliant on this condition. Once they gain freedom, the slaves use their wages to "float a company".

Meanwhile, the residents move into the first building of the Mansions of the Gods. The residents are from middle class Roman society and are selected by lottery. Once the Romans begin to shop at the local markets and this causes a price war, with Gauls attempting to sell "antique" weapons and fish to the Romans. To bring this to an end, Astérix approaches Anglaigus (Squareonthehypotenus) and asks for an apartment. Anglaigus (Squareonthehypotenus) refuses, telling Astérix that the building is full. Obélix, pretending to be a rabid monster, drives out a couple from the building and Astérix returns and arranges for the baird, Assurancetourix (assurance tous risques, Cacofonix in English), to move into the vacant apartment. Assurancetourix (Cacofonix) drives out the remainder of the residents with his terrible discordant singing practice, which he does at night. The Romans return to Rome.

Desperate, Anglaigus (Squareonthehypotenus) fills the empty apartments with soldiers and throws the baird out. The Gauls take great offence to his expulsion and attack the colony. The architect decides to leave and sets his eyes on Egypt, where he will have "nice, quiet tenants" (Goscinny and Uderzo, p. 102)*. The Gauls celebrate their victory, while the sacred grove regenerates almost instantaneously thanks to Panoramix (Getafix)’s potion, covering the ruins of the mansion.

* Summary based on: R. Goscinny and A. Uderzo, “An Asterix Adventure. The Mansions of the Gods” in Asterix Omnibus 6, London: Orion Children’s Books, 2012, 59–103.

Analysis

The Mansions of the Gods is a humorous story set during the Gallic wars. The wars were a series of Roman military campaigns against Gaulish tribes led by Julius Caesar, a proconsul. These campaigns took place between 58 AD and 50 AD. The Gauls were Celtic peoples who resided primarily in France and the Alps. The comic draws on major cultural symbols, themes and issues related to the Roman and Gaul interaction and through subversive humor, engages the reader in a discourse about modern life, with particular emphasis on topics such as capitalism, worker’s rights, business and the domination and destruction of the environment.

The narrative juxtaposes the Roman and Gaulish cultural landscapes. While both cultures shared "an agricultural and pastoral heritage" that developed over time, their settlement patterns and cultural beliefs and practices had different manifestations.* In general, at the time of the Gallic wars, the Celtic settlement pattern comprised small and scattered villages. Residential buildings were constructed from timber and stone and roofs were thatched. Celtic religious architecture has rarely survived archaeologically into the present and classical sources rarely wrote about them in detail.** From what is currently known, temples were often large open spaces, demarcated with a ditch, while at other times, timber structures were erected.*** The sacred grove was an axis mundi, a centre of the Celtic world, often populated by oak trees.**** Importantly, the grove is the main setting of the story. It is the proposed site for the Roman residential development called the "Mansion of the Gods". In contrast, the Roman settlement pattern comprised major towns, rural settlements and estates. Roman towns evolved from the Etruscan and Greek-Hellenistic architectural traditions and were well planned, featuring major religious and civic structures, open arenas, and gardens.***** Temples also formed an integral part of Roman culture. Every major town erected a temple dedicated to the main Roman gods, and these were places of public ceremony.****** While few have survived in a complete state, these buildings were built using materials, such as cement, brick and stone and were commonly decorated with frescoes that depicted various scenes of Roman life. As Summerson******* observes, the Roman temple continues to be recognised as an "obvious symbol of Roman architecture". The comic highlights a number of these fundamental differences of the Roman and Gaul settlement pattern. This is best illustrated at the beginning (see Goscinny and Uderzo, p. 60)********, where a plan of the future Roman settlement is displayed.

Importantly, the juxtaposition of the Roman and Gaul cultures sets the foundation for the clever subversion of major cultural symbols and archetypes. For example, the Roman temple is symbolically evoked by the name of the proposed development, "The Mansions of the Gods". In fact, Anglaigus (Squareonthehypotenus) initially wants to call it "Rome, New Town", but Caesar refuses. In his mind, there was only "one Rome" (Goscinny and Uderzo, p. 62). Yet, as the reader soon discovers, the complex is not intended for religious purposes; it is simply an extensive residential complex. By subverting this major symbol in this way, the authors draw parallels between the Roman domestication of the Gaulish village and the nature of modern urban development. Through their behaviour and language, the Romans are characterised as enterprising business men; they plan and build the complex for the purposes of generating revenue and to provide superior living conditions for the privileged ruling class, the Roman elite. Once complete, the complex is even marketed as a place where a person can live "a healthy and happy life worthy of a god" (Goscinny and Uderzo, pp. 84–85). This conjures the idea that the Roman ruling class could almost become a deity simply by purchasing and taking up residence at the complex.

The portrayal of the Romans as shrewd businessmen invites the reader to reflect on a number of key issues and topics, including how different cultures view the natural world and the other, including subjugated groups. The authors create a relationship of domination between the Romans and the natural world. Anglaigus (Squareonthehypotenus)’ vision is portrayed as a commercial enterprise, which gives little consideration to the intrinsic and intangible qualities of the grove. In fact, the grove is seemingly viewed as an inanimate surface. However, it is important to highlight that the Roman relationship with the natural world was, in fact, complex and changed over time. Their ideological beliefs and notions were based on their domain, the Mediterranean and Western European landscape. One central tenet of their worldview was that Nature and humanity were connected by "divine emanations from a supreme creative force" and Nature played an active role in people’s lives.********* For example, early literary sources, such as Aristotle and Plato, emphasised that leaders needed to establish and maintain "harmonious relationships" with natural forces in order to demonstrate their authority. Such ideas were derived from Stoicism, a Greek school of thought. Omens and portents gained through divinatory rituals were a necessary mandate for leadership.********** However, by the time Julius Caesar invaded Gaulish territories, there were gradual but major ideological changes taking place. For example, from around 44 BCE, Cicero began to argue against divination.*********** Cicero (see 4–12, for instance)************ argued that it was superstition and caused diviners to relinquish their reason in order to enter "passive" relationships with divine forces. Ultimately, it could be argued that the characterisation of the Roman’s view of Nature in the comic is an allegory for the way capitalistic societies dominate the natural world, viewing it simply as a commodity. The origin of these contemporary attitudes has been traced back to the Renaissance (see Leiss).**************

As a second and an interrelated point, Roman domestication of foreign territories is portrayed as a ruthless process during which non-Roman sacred places were destroyed, with the intention to "civilised" subjugated peoples. Importantly, the architectural complex, The Mansions of the Gods, is cast as a symbol of civilization. The current research suggests, once again, that the actual historical picture was more complex. Generally, Romans ideally respected local religions, even though non-Roman shrines were not necessarily viewed as "sacred".*************** Classical sources, such as Cicero, reflect the collective Roman view that temples and shrines were sacred and should not be desecrated. Such an attitude was, therefore, demonstrative of the Roman pietas (their "devotion" and "duty’), a highly esteemed virtue in the classical world.**************** Despite this attitude, there is considerable archaeological and historical evidence that indicates that the Romans strategically and systematically destroyed sacred places, especially in Gaulish territory.**************** Places were destroyed during warfare, as seen in the case of the temple of Mesopotamon in Epirus, Greece, which was razed and all religious objects were removed from the site.***************** This destruction under warfare may have been legally sanctioned under laws, such as the lex reptundae.****************** In the case of Gaulish territories, the Romans destroyed sacred places, including groves, for a range of reasons. As Rutledge******************* highlights, the Romans systematically destroyed shrines in order to remove any potential threat or challenge to their authority. Tacitus (1.50–51) provides two important examples; the destruction of the temple; and, the grove dedicated to Tanfana, a Germanic goddess, during Germanicus’ campaign in AD and 20 AD.******************** Tacitus (14.30) also related that Suetonius Paulinus, a Roman commander, invaded Mona, a Scottish island populated by sacred groves. There, a group of Britons had taken refuge, along with their druidic leaders. To stamp out their rites, Paulinus ordered that the groves be cut down. Meanwhile, the Romans also destroyed sites for the purposes of gathering resources. For example, Caesar reportedly had the grove at Masilia, France, which was of great religious significance, cut down for timber to construct ships*********************(see Luc.2.299–452). Notably, this historical example is congruent with the comic’s storyline. However, as the story progresses, the reader gains the impression that Anglaigus (Squareonthehypotenus) and his team view the grove as an obstacle to civilising the Gauls.

Finally, a power struggle between the Romans and slaves is used as an allegory in the narrative to deliver broader socio-political messages about modern working conditions. In particular, it is suggested that working is a modern form of slavery. Initially, the authors characterise Romans and the slaves in a historical and stereotypical relationship, with the Romans acting as the master or owner and subjugated people as their legal property. Notably, slavery in the classical world was universal and slaves generally fell into two main types in Greek and Roman society; native slaves (oikogeneis, vernae) and those who were brought from the outside.********************** Generally, the Roman elite retained slaves as a symbol of status and ordered them to perform tasks and services that were dangerous, difficult or considered to be beneath them.*********************** Slaves were, at times, also given supervisory roles, such as overseeing city accounts, and they were assigned these responsibilities because they were "an outsider" and therefore, could not contribute to important matters relating to the state and its citizens.************************ The slaves of Anglaigus (Squareonthehypotenus) fall under the second main category and represent different territories invaded by the Romans, including Belgium and Iberia (Goscinny and Uderzo, p. 66). Notably, Numdian, named after his homeland, is nominated as the "leader" of the slaves and later uses his position to try to negotiate better working and living conditions.

The comic explores the subject of violence against slaves. In the Roman world, slaves were occasionally subjected to ill-treatment and brutality.************************* At times, in the comic, the Romans make threats of violence as a mechanism of control and with the intention of making the slaves work longer and harder. For example, Anglaigus (Squareonthehypotenus) threatens to make the slaves "work until dawn" or they will be "skinned" (Goscinny and Uderzo, p. 67). Cleverly, through this dialogue, the authors symbolically represent the Roman slaves as modern workers, suggesting that the modern employee’s "master" is working them like a slave.

The power relationship between the Romans and slaves changes when Astérix gives the Numidian a potion, hoping it will cause the slaves to rebel and flee. Instead, Numidian attempts to negotiate better conditions, acting like a union leader. He resorts to beat a commander when his request is refused (Goscinny and Uderzo, pp. 75–77). This act of violence starts a revolt and the Romans concede to their requests in order to bring them under control. Eventually, the slaves are released but do not return home. Instead, they decided to become enterprising "pirates" who will "float a company" (Goscinny and Uderzo, p. 87). Here, the authors seem to suggest that entrepreneurship grants an individual freedom, as it enables them to escape the "slavery" of employment.

It is important to highlight that the Gauls, as principally represented by the characters Astérix, Obélix and Panoramix (Getaflix), are diametrically opposed to the Romans; they are cast as stewards of Nature. They help the grove magically rejuvenate using Panoramix (Getaflix)’s magical seeds, which are reminiscent of the magical beans from Jack and the Beanstalk, an English folktale immortalised by Joseph Jacob (1860/1890). The comic casts the druid in the archetypal role as the alchemist and intermediary, but also as a guardian of Nature. The druid as a conservationist is a modern idea, as Miranda-Green highlights**************************. The grove’s magical rejuvenation is part of a satirical and playful reimagining of historical events, which suggest in jest that the Roman’s campaigns against the Gauls were doomed from the very beginning, for the druidic power derived from the regenerative powers of Nature was stronger, and destined to be drive the Romans out.

The comic remains an important and relevant narrative, affording opportunities to debate key contemporary issues. It can inspire children to reflect on the long-term effects of climate change brought about by factors, including deforestation and rapid urbanisation of landscapes. It also encourages us to think about our relationship with the natural world and the ways that classical cultures and other cultural traditions viewed them. Finally, this book also provides a platform for discussing the conflicts and tensions between employers, and unions and equal rights movements, while also considering the nature and meaning of work in the 21st century.

* Martin Henig, Religion in Roman Britain, London: BT Batsford Ltd., 1984, 10.

** Miranda Green Aldhouse, Exploring the World of the Druids, Thames and Hudson, 1997.

*** M. Henig, op. cit., 5.

****M. Green-Aldhouse, op. cit., 108.

***** Louise Cilliers and Francois Pieter Retief, “City Planning in Graeco-Roman Times with Emphasis on Health Facilities”, Akroterion 51 (2006): 43–56.

****** John Summerson, The Classical Language of Architecture, Thames and Hudson "World of Art" series, 1980; Sarah Iies Johnston, ed., Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide, Cambridge, Harvard: University Press, 2004, 278.

******* J. Summerson, op. cit., 25.

******** Analysis based on: R. Goscinny and A. Uderzo, “An Asterix Adventure. The Mansions of the Gods” in Asterix Omnibus 6, London: Orion Children’s Books, 2012, 59–103.

********* Walter Roberts, “Greco-Roman Conceptions of the Natural World, Religion and Leadership in Later Roman Empire” in Arri Eisen and Gary Laderman, eds., Science, Religion and Society: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Controversy, London: Routledge, 2015, 244–250.

********** Ibidem, 245–246.

*********** Ibidem, 245.

************ Cicero, De Divinatione. Book I, Loeb Classical Library, 1923.

************* William Leiss, The Domination of Nature, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1994.

************** Steven H. Rutledge, “The Roman Destruction of Sacred Sites”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte 52.1 (2007): 179–195, 194–195.

*************** Ibidem, 194.

**************** Ibidem.

***************** Ibidem, 180, 182.

****************** Ibidem, 193.

******************* Ibidem, 190–191.

******************** Ibidem, 190.

********************* Ibidem, 186.

********************** Thomas Wiedemann, Greek and Roman Slavery, London, Routledge, 2003, 6.

*********************** Ibidem, 5, 8.

************************ Ibidem, 8.

************************* Ibidem, 11.

************************** Miranda Green Aldhouse, Exploring the World of the Druids, Thames and Hudson, 1997, 197.

Further Reading

Cicero, De Divinatione. Book I, Loeb Classical Library, 1923.

Tacitus, Annals, penelope.uchicago.edu (accessed: January 29, 2021).

Cilliers, Louise and Francois Pieter Retief, “City Planning in Graeco-Roman Times with Emphasis on Health Facilities”, Akroterion 51 (2006): 43–56.

Green Aldhouse, Miranda, Exploring the World of the Druids, Thames and Hudson, 1997.

Henig, Martin, Religion in Roman Britain, London: BT Batsford Ltd., 1984.

Johnston, Sarah Iles, Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide, Cambridge, Harvard: University Press, 2004.

Leiss, William, The Domination of Nature, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1994.

Roberts, Walter, “Greco-Roman Conceptions of the Natural World, Religion and Leadership in Later Roman Empire” in Arri Eisen and Gary Laderman, eds., Science, Religion and Society: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Controversy, London, Routledge, 2015, 244–250.

Rutledge, Steven H., “The Roman Destruction of Sacred Sites”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte 52.1 (2007): 179–195.

Summerson, John, The Classical Language of Architecture, Thames and Hudson "World of Art" series, 1980.

Wiedemann, Thomas, Greek and Roman Slavery, London, Routledge, 2003.

Addenda

Entry based on: R. Goscinny and A. Uderzo, “An Asterix Adventure. The Mansions of the Gods” in Asterix Omnibus 6, London: Orion Children’s Books, 2012, 59–103.