Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

René Goscinny, Albert Uderzo, "Astérix chez les Helvètes", Pilote 557–578 (1970), 48 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Comics (Graphic works)

Target Audience

Crossover

Cover

We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover.

Author of the Entry:

Lisa Dunbar Solas, OMC contributor, drlisasolas@ancientexplorer.com.au

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

René Goscinny

, 1926 - 1977

(Author)

René Goscinny was born in 1926 in Paris. He was the son of Jewish immigrants to France from Poland. Born in Paris, he moved with his family to Buenos Aires, Argentina, at the age of two. In 1943 he was forced into work by his father’s death, eventually gaining work as an illustrator in an advertising firm. Living in New York by 1945, Goscinny was approaching the usual age of compulsory military service. However, rather than join the United States Army, he elected to return to his native France to complete its year-long period of service. Throughout 1946, Goscinny was with the 141st Alpine Infantry Battalion, and found an artistic outlet in the unit’s official and semi-official posters and comics. His first commissioned illustrated work followed in 1947, but he then entered into a period of hardship upon moving back to New York City. Some important networking occurred thereafter with other emerging comic artists, before Goscinny returned to France in 1951 to work at the World Press Agency. There, he met lifelong collaborator, Albert Uderzo, with whom he co-founded the Édipresse/Édifrance syndicate and began publishing original material.

As Edipresse/Edifrance developed, Goscinny continued to work across a number of publications in the 1950s, including Tintin magazine from 1956. A key output from this period was a collaboration with Maurice De Bevere (1923–2001). They created together series of comics: about Lucky Luke (with Maurice), and about Asterix (with Uderzo). Goscinny worked with Jean Jacques Sempe and they created a series about boy called Nicolas.

The following year (1959), the syndicate launched its own magazine, Pilote; and the first issue contained the earliest adventure of ‘Astérix, the Gaul’, scripted by Goscinny himself, and drawn by Uderzo. On the back of Astérix, Pilote was a huge success, but managing a magazine was a challenge for the members of the syndicate. Georges Dargaud (1911–1990) – publisher of Tintin, and a major force in Franco-Belgian comics – saw the opportunity to purchase Pilote in 1960, and put it on a firmer footing, financially. Already the leading script-writer on the magazine, Goscinny was co-editor-in-chief of Pilote from 1960. Such was its success that by 1962, he was able to leave Tintin magazine in to edit Pilote full-time, and he held that role until 1973.

Goscinny’s success with Astérix and Lucky Luke (published in serialized instalments in the magazine, as well as in album-form by Dargaud) saw him enjoy a comfortable life, but this arguably contributed to his growing ill-health. He had married in 1967 – to Gilberte Pollaro-Millo – and a daughter – Anne Goscinny – was born the following year, as he continued to work with Uderzo and others. Pilote and Astérix were sufficiently profitable to be a full-time job, and twenty-three Astérix adventures were completed by 1977, when Goscinny died suddenly of a cardiac arrest during a routine stress test. Uderzo completed the story Astérix chez les Belges [Asterix in Belgium] and continued the series alone.

Goscinny was not only a comic book author but also a director and co–director of animated movies (Daisy Town, Asterix and Cleopatra), feature movies (Les Gaspards, Le Viager). Goscinny. He died in 1977 in Paris.

Sources:

bookreports.info (accessed: September 14, 2018)

britannica.com (accessed: September 14, 2018)

lambiek.net (accessed: September 14, 2018)

Bio prepared by Agnieszka Maciejewska, University of Warsaw, agnieszka.maciejewska@student.uw.edu.pl and Richard Scully, University of New England, Armidale rscully@une.edu.au

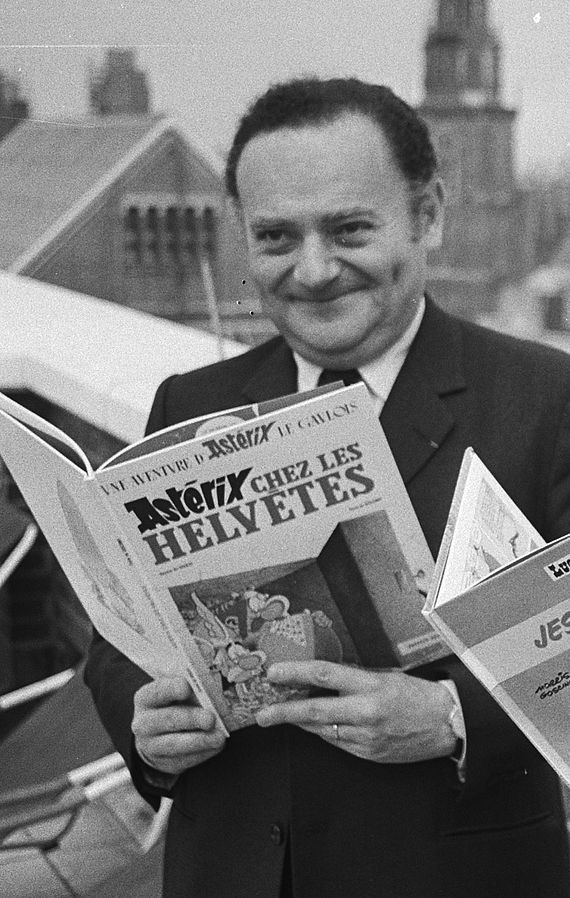

Albert Uderzo in 1973 by Gilles Desjardins. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 (accessed: December 30, 2021).

Albert Uderzo

, 1927 - 2020

(Illustrator)

Albert Uderzo was born in Fismes, France, in 1927. The son of Italian immigrants, he experienced discrimination following the family’s move to Paris, at a time when Fascist Italy was pursuing an aggressive course, internationally (on top of the usual xenophobia directed at immigrants). Uderzo came into contact with American-imported comics around the late 1930s (including Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck). He also discovered that he was colour-blind (despite art being the only successful aspect of his schooling career). Living in German-occupied France, from 1940, Uderzo tried his hand at aircraft engineering, but illustration was where he found his métier. Post-war, he came into contact with the circles of Belgian-French comics artists; as well as meeting and marrying Ada Milani in 1953 (who gave birth to a daughter, Sylvie Uderzo in 1953).

He started his career as an illustrator after World War II. In 1951, he met René Goscinny at the World Press Agency. Together, they worked on a comic: ‘Oumpah-pah le Peau-Rouge’ [Ompa-pa the Redskin] – drawn by Uderzo and written by Goscinny. In 1959 Uderzo and Goscinny were editors of Pilote magazine. They published there their first Asterix episode which became one of the most famous comic stories in history. Individual albums of Astérix adventures appeared regularly from 1961 (published by Georges Dargaud following the completion of the serialized run in Pilote), and there were 23 completed adventures by the time Goscinny died in mid-1977. After Goscinny’s death, Uderzo took over the writing and continued publishing Asterix adventures, and completed 11 further albums by retirement in 2011 (including several that were compendiums of older material, co-created by Goscinny). In the late 2000s and early 2010s, Uderzo experienced considerable family disquiet; largely over the financial benefits expected to accrue to his daughter. Although maintaining for much of his career that Astérix would end with his death, he agreed to sell his interest in the character to Hachette Livre, who has continued the series since 2011, owing to the talents of Jean-Yves Ferri and Didier Conrad.

All stories about Asterix published till now are very successful and widely known. They are highly popular not only in France but have been translated into one hundred and ten languages and dialects. The series continues and Asterix (Le papyrus de Cesar) became the number one bestseller in France in 2015 with 1,619,000 copies sold. The sales figures and popularity of Asterix series are comparable with the Harry Potter phenomenon. Astérix et la Transitalique published in “2017 placed 76 among the French Amazon best sellers three weeks before it was published Among comic books for adolescents the title was number one, among comic books of all categories it was number two.”*

Albert Uderzo died on 24 March 2020.

Sources:

lambiek.net (accessed September 14, 2018).

Bio prepared by Agnieszka Maciejewska, University of Warsaw, agnieszka.maciejewska@student.uw.edu.pl and Richard Scully, University of New England, Armidale rscully@une.edu.au

*See Elżbieta Olechowska, “New Mythological Hybrids Are Born in Bande Dessinée: Greek Myths as Seen by Joann Sfar and Christophe Blain” in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Chasing Mythical Beasts…The Reception of Creatures from Graeco-Roman Mythology in Children’s & Young Adults’ Culture as a Transformation Marker, forthcoming.

Translation

Catalan: Astèrix al país dels helvecis

Croatian: Asteriks kod Helvećana

Czech: Asterix v Helvetii

Danish: Asterix i Alperne

Dutch: Asterix en de Helvetiërs

Finnish: Asterix ja alppikukka

Galician: Astérix na Helvecia

German: Asterix bei den Schweizern

Greek: Ο Αστερίξ στους Ελβετούς

Icelandic: Ástríkur í Heilvitalandi

Italian: Asterix e gli Elvezi

Latin: Asterix apud Helvetios

Norwegian: Asterix i Alpene

Polish: Asteriks u Helwetów

Portuguese: Astérix entre os Helvécios

Serbian: Asteriks u Helveciji

Spanish: Astérix en Helvecia

Swedish: Asterix i Alperna

Turkish: Asteriks İsviçre'de

Summary

Asterix in Switzerland is the 16th book of the Astérix adventures comic book series (see also entries for Book 4, Book 6, and Book 12).

The comic opens with Abraracourcix (à bras raccourcis, Vitalstatistix in English) sacking his shield bearers and nominating Astérix and Obélix as their replacements. While Astérix tries to object, the chief orders them to start immediately. Meanwhile, Gracchus Garovirus (gare au virus, Varius Flavus in English), Condate's (Condatum) Roman Governor, is holding an orgy. The lavish party is first interrupted by the delivery of a large sum of gold raised by Roman local taxes. It is then revealed that Gracchus Garovirus (Varius Flavus) is embezzling the majority of the money to finance his lavish and indulgent lifestyle and also his retirement. However, tax inspector Claudius Malosinuus (quaestor Vexatius Sinusitis in English) is sent to investigate Garovirus (Flavus) and arrives during the orgy. Garovirus (Flavus) discovers that the Quaestor will not be bribed, so he decides to poison him. After encouraging the tired man to rest after his long journey, Garovirus (Flavus) mixes poison into his vegetable soup and the Quaestor becomes violently ill and demands to see a doctor. To buy time, Garovirus (Flavus) makes pitiful excuses for the doctor's delay.

The astute Quaestor catches on to Garovirus (Flavus)' murderous plan, and then sends for the druid, Panoramix (Getafix in English). Panoramix (Getafix) immediately identifies the cause of his malady and then consents to make the remedy, but requires a flower called "silver star" (edelweiss) as an essential ingredient. The druid sends Astérix and Obélix to Helvetia to acquire it. Helvetia is the Latin name of the Gaulish tribe who resided in Switzerland. Panoramix (Getafix) requests that the Quaestor remain in the village as a hostage to ensure that the Gauls safe return.

While the Gauls are en route to Helvetia, Garovirus (Flavus) sends word to the Roman governor, Caius Diplodocus (Curius Odus in English), who is equally corrupt. His soldiers create obstacles as soon as the Astérix and Obélix arrive at the border, delaying their mission. The Gauls escape and make it to a hotel managed by Petisuix (petit-suisse, Petitsuix in English). However, the soldiers soon discover their location and storm the hotel. The manager warns the Gauls and hides them until the Romans leave. The Gauls flee to a bank, where Zurix, the bank manager, helps them hide in a large safe, which they soon after break out of. Zurix then places them in a second safe just as the soldiers arrive. The soldiers soon notice the broken safe. Zurix tries to cover the Gaul's tracks by claiming that it was broken into, but his flawed reason causes the Romans to lose confidence in the bank's security. Once they are satisfied that the Gauls are not at the bank, they leave threatening to return to close their accounts.

The following morning, the Gauls leave the bank and make it to Lake Geneva, with the Roman army once again in hot pursuit. They make it onto a boat, which takes them to a celebration held by a group of Helvetian veterans. During this event, Obélix becomes intoxicated by drinking plum wine. Astérix accompanied by the veterans continues their mission climbing up the mountain, tied to a drunk Obélix. On the mountain, they finally discover the rare flower.

The successful pair returns to their village, where Panoramix (Getafix) makes the remedy with the flower. Quaestor Claudius Malosinus (Vexatius Sinusitis) is then cured. He is also empowered by the potion, and punches Garovirus (Flavus), declaring that he will expose not just him but also Caius Diplodocus (Curius Odus), and their next "orgy" will be at the "circus," meaning their execution.

The story comes to a close with the Gauls holding their banquet in celebration of the Gaul’s return and they invite Malosinus (Sinusitis) as their very first Roman guest.

Analysis

Asterix in Switzerland is a humorous story set during the Gallic Wars. The comic draws on major cultural symbols, themes and issues related to the Roman and Gaul interaction and through subversive humour, engages the reader in a discourse about modern life, with particular emphasis on topics such as equality, corruption and capitalism.

The authors bring to light the realities of corruption through a range of scenarios, and in particular, through the portrayal of Gracchus Garovirus (Varius Flavus), the main villain of the story. Notably, the character's English name is a clever wordplay by Anthea Bell, who translated the comic into English. It is derived from "various flavours" and this seems a tongue-in-cheek reference to the essence of his character. He possesses a greedy and varied appetite for sex, money and luxury. He abuses his public position and engages in a range of illegal activities, including embezzlement and attempted murder, in order to satisfy his appetite. The morally and politically corrupt Garovirus (Flavus), therefore, subverts the classical and modern notion of a model public servant. Notably, Roman government officials were bound to serve for the common good and not just for their own interests (Hill, 2013, p. 576). The Romans possessed a notion of political corruption similar to that of contemporary times and cases of bribery and embezzlement were reported, especially during times of political instability (Hills 2013, pp. 571, 576–577). Significantly, Garovirus (Flavus) is not the only corrupt governor; Governor Caius Diplodocus (Curius Odus) is also abusing his position. Here, the authors subtly suggest that corruption is not just deviant behaviour, but a social problem that has perverse effects.

Meanwhile, Claudius Malosinus (Vexatius Sinusitis) Quaestor represents the oppositional archetype to the high-ranking, villainous and corrupt governor; he is an upstanding model Roman citizen and tax controller. Like Garovirus (Flavus), his name also highlights the essential qualities of his character and his role in the story. Quaestor was a low-ranking public office position. Citizens acting in this position looked after the financial administration of Rome. Notably, the character's name also refers to his disruptive and irritating nature. "Vexatius" is derived from "vexatious," while "sinusitis" is a medical condition where the sinus becomes inflamed. His name cleverly refers to his ability to "get up the nose" of officials and spoil their devious and corrupt plans and dealings.

Interestingly, the authors seemingly draw on ancient Roman use of poisons to further highlight the governor's corrupt nature. Garovirus (Flavus) attempts to murder Quaestor through poisoning. He uses a powder, concealed in his ring. This unknown powder acts as an instrument of corruption. Notably, the authors may have drawn inspiration from Roman history when developing the plot. During tumultuous political periods, such as between 1 AD and 2 AD, there were increased reports of the poisoning of public servants, including emperors, as part of "political intrigues" (Retief and Cilliers, n.d). Vegetable poisons containing belladonna alkaloids were often used (Retief and Cilliers, n.d.).

Meanwhile, the plant, known as the silver flower, acts as an antidote. It also helps to drive the plot. Importantly, the child-like Astérix and Obélix serve as the sidekicks of Panoramix (Getafix). In the story, Panoramix (Getafix) serves as the intermediary and saviour, who holds the knowledge and skill to save the Quaestor, and indirectly seal Garovirus (Flavus)' fate. Meanwhile, Astérix and Obélix take on a mission that is somewhat reminiscent of the search for the Holy Grail. Just like the grail, the flower has miraculous powers and is difficult to find. From a botanical perspective, the plant possesses unusual foliage and is delicate. As a result, it has acquired different common names, including edelweiss ("noble white") (Davis 2018). It grows in the mountains and is part of the daisy family (Asteraceae). It has been used medicinally to cure respiratory and gastrointestinal disorders. For many centuries, it was believed that the flower was rare, growing only on mountain slopes and summits. Gradually, because of this belief, the plant became a symbol of "bravery" and "courage" for alpine climbers (Davis 2018). The authors cleverly mock the plant's popularised myth in the humorous scene where Astérix and the Swiss Gauls form a team and trek up a steep, snow-capped mountain, with an intoxicated Obélix, in order to procure the flower (see Goscinny and Uderzo 2004, pp. 52–53, in particular). Importantly, it is teamwork that ensures the Gaul's success and at the end of this mission, the flower not only represents an antidote, but also a substance that counteracts greed and evil.

As a final point, the comic may also be considered a late example of post-1945 media texts, which cast imperial Rome in a negative light. As Winkler (1997–1998) observed, in the immediate years following the end of the Second World War, American cinema made a series of epic films about ancient Rome and few were historically accurate. The majority generated analogies between the empire and the Nazi regime. As a result, filmmakers presented ancient Rome as "a military dictatorship which ruthlessly exterminates all resistance to its dominance and enslaves the conquered" (Winkler 1997–1998, p. 168). Around the same time, other popular culture texts presented related narratives. A major theme is a resistance and liberation from oppressive regimes. The Sound of Music (1965), which centres on an Austrian family's loss of their home to the Nazis, is the best-known example. Notably, the narrative was particularly important to Austria; it underpinned its national identity (Lamb-Faffelburger 2003, p. 289).

In an entertaining but subtle way, the authors also mock central symbols representing modern capitalism, including banks and businesses. Notably, Astérix and Obélix seek help from Helvetian private businesses and in particular, the bank manager, Zurix. Significantly, the character's name is derived from Zurich, which is the name of the largest city in Switzerland. However, considering his role in the story, his name also refers to the Zurich bank. Importantly, Switzerland is considered a modern tax haven for foreign account holders and investors. The relationship between the bank and foreign investors is subtly referred to during Zurix's interaction with Roman soldiers. When Zurix hides Astérix and Obélix in the second safe as the Roman's arrive, the reader sees that it holds foreign and valuable objects, including Egyptian relics, presumably obtained through gift-giving between dignitaries and the sacking of places during warfare (see Goscinny and Uderzo 2004, p. 39). Notably, the manager decides to help the Gauls "out of sympathy" for the Gauls, explaining that the Romans also detest the Gauls of Helvetica (see Goscinny and Uderzo 2004, p. 37). Yet, his decision places the bank's future in jeopardy. Here, the authors seem to subtly by banding together the power of groups and organisations can be usurped.

In summary, this comic invites readers to explore the realities of corruption and capitalism. In particular, they are afforded the opportunity to reflect on how corruption can act as a barrier to equality and democracy and how it can be potentially subverted.

Further Reading

Goscinny, R. and A. Uderzo, "Asterix in Switzerland", in Asterix Omnibus 6, Orion Children’s Books, 2012, 11–56.

Davis Pluess, Jessica, The mystical and mythical edelweiss, published July 8, 2018, online, houseofswitzerland.org (accessed: June 23, 2021).

Hill, Lisa, "Conceptions of political corruption in ancient Athens and Rome", History of Political Thought 34.4 (2013): 565–587.

Lamb-Faffelberger, Margarete, "Beyond 'The Sound of Music': The quest for cultural identity in modern Austria", The German Quarterly 76.3 (2003): 289–299.

Retief, Francois and Louise Cilliers, "Poisons, poisoning poisoners in ancient Rome", Medicina Antiqua, online, www.ucl.ac.uk (accessed: July 5, 2021).

Winkler, Martin M., "The Roman empire in American cinema after 1945", The Classical Journal 93.2 (1997): 167–196.