Title of the work

Studio / Production Company

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

Running time

Format

Date of the First DVD or VHS

Awards

2010 – Golden Schmoes Awards;

2010 – Golden Schmoes (Nominee);

2010 – Biggest Disappointment of the Year;

2010 – IGN Summer Movie Awards;

2010 – IGN Award (Nominee);

2010 – Best Fantasy Movie;

2010 – Irina Palm d'Or;

2010 – Irina Palm (Nominee);

2010 – Worst British Supporting Actor: Liam Neeson;

2010 – Teen Choice Awards;

2010 – Teen Choice Award (Nominee);

2010 – Choice Movie: Breakout Female: Gemma Arterton;

2010 – Choice Movie: Fantasy;

2010 – Choice Movie Actor: Fantasy: Sam Worthington;

2010 – Scream Awards;

2010 – Scream Award (Nominee);

2010 – Best Cameo: Bubo The Mechanical Owl;

2010 – Fight Scene of the Year: For "Perseus and the Heroes vs Medusa";

2011 – Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films, USA;

2011 – Saturn Award (Nominee);

2011 – Best Fantasy Film;

2011 – Alliance of Women Film Journalists;

2011 – EDA Special Mention Award (Winner);

2011 – Remake That Shouldn't Have Been Made;

2011 – Annie Awards;

2011 – Annie (Nominee);

2011 – Best Character Animation in a Live Action Production: Quentin Miles, Warner Bros., Legendary Entertainment;

2011 – ASCAP Film and Television Music Awards;

2011 – ASCAP Award (Winner);

2011 – Top Box Office Films: Ramin Djawadi;

2011 – Razzie Awards;

2011 – Razzie Award (Nominee);

2011 – Worst Eye-Gouging Mis-Use of 3-D;

2011 – Worst Prequel, Remake, Rip-Off or Sequel: Warner Bros., Legendary Entertainment, The Zanuck Company;

2011 – Yoga Awards;

2011 – Yoga Award (Winner);

2011 – Worst Foreign Actor: Ralph Fiennes.

Genre

Fantasy films

Target Audience

Crossover

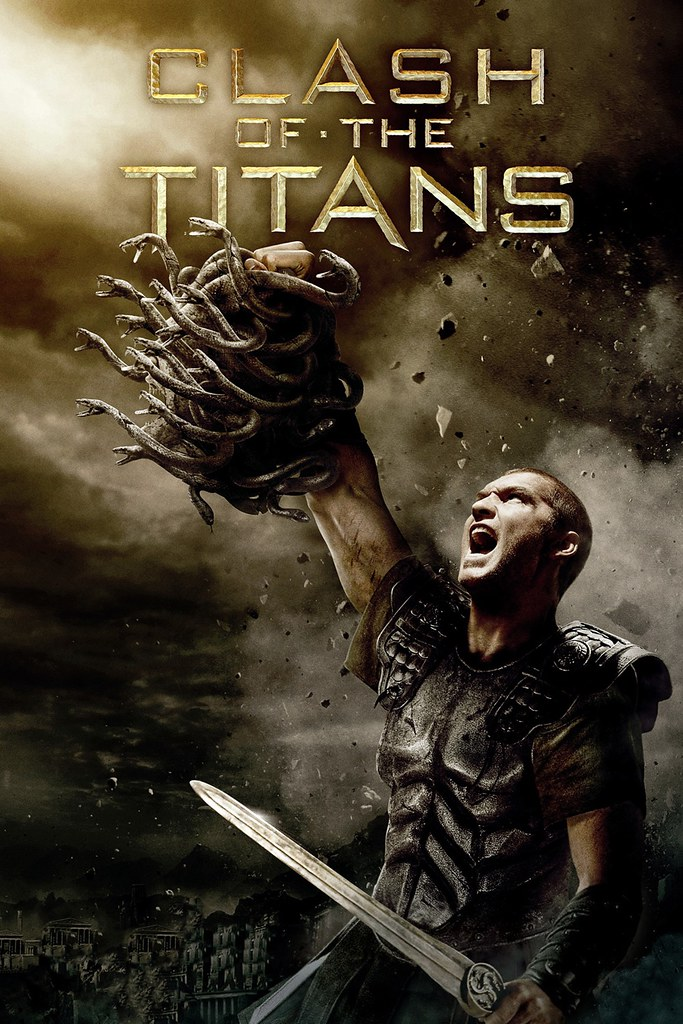

Cover

Clash of the Titans (2010) poster by Hutson Hayward. Retrieved from flickr.com, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (accessed: February 7, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Aimee Hinds, University of Roehampton, hindsa@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Travis Beacham by Dominic "Count3D" Dobrzensky. Retrieved from Wikipedia, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 (accessed: February 7, 2022).

Travis Beacham

, b. 1980

(Screenwriter)

Travis Beacham is an American screenwriter. Beacham studied screenwriting at University of North Carolina School of Arts, graduating in 2005 and working on his first film during his time at university. His first script, A Killing on Carnival Row, was eventually picked up as Amazon Prime's 2017 series Carnival Row. He is best known for writing 2013's Pacific Rim (for which he also authored a graphic novel), and in 2012 he made his debut as a director with The Curiosity.

Source:

Wikipedia (accessed: June 10, 2021).

Bio prepared by Aimee Hinds, University of Roehampton, hindsa@roehampton.ac.uk

Phil Hay (Screenwriter)

Phil Hay is an American screenwriter. Originally from Ohio, Hay attended Brown University where he met his long-time writing partner, Matt Manfredi. Hay frequently collaborates with his filmmaker wife Karyn Kusama. He is best known for films such as Crazy/Beautiful (2001), Æon Flux (2005), Clash of the Titans (2010), and R.I.P.D. (2013).

Source:

Wikipedia (accessed: June 10, 2021).

Bio prepared by Aimee Hinds, University of Roehampton, hindsa@roehampton.ac.uk

Louis Leterrier by Gage Skidmore, 2019. Retrieved from Wikipedia, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 (accessed: February 7, 2022).

Louis Leterrier

, b. 1973

(Director)

Louis Leterrier is a French director and producer. Leterrier initially trained in advertising and publicity before studying filmmaking at New York University. Early in his career he worked with the French director Luc Besson on commercials and the 1999 Joan of Arc. Working under other directors, he was also involved with the 1997 Alien Resurrection and the 2002 Astérix & Obélix: Mission Cléopâtre. His first big budget film was the 2008 The Incredible Hulk, followed in 2010 by the remake of the 1981 film Clash of the Titans. He is also known for The Transporter (2002), Now You See Me (2013), Grimsby (2016), and the series The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance (2019).

Sources:

Wikipedia (accessed: June 10, 2021).

IMBd (accessed: June 10, 2021).

Bio prepared by Aimee Hinds, University of Roehampton, hindsa@roehampton.ac.uk

Matt Manfredi

, b. 1971

(Screenwriter)

Matt Manfredi is an American screenwriter. Manfredi was born in California, and met his long-time writing partner Phil Hay while attending Brown University. Manfredi went on to get a Master's degree in screenwriting from the American Film Institute. He is best known for films such as Crazy/Beautiful (2001), Æon Flux (2005), Clash of the Titans (2010) and R.I.P.D. (2013), and he has the sole writing credit on Bug (2002) which he directed with Phil Hay.

Source:

Wikipedia, Matt Manfredi, Phil Hay (accessed: June 10, 2021).

Bio prepared by Aimee Hinds, University of Roehampton, hindsa@roehampton.ac.uk

Casting

Liam Neeson – Zeus,

Gemma Arterton – Io,

Ralph Fiennes – Hades,

Aleva Davalos – Andromeda,

Jason Flemyng – Calibos/Acrisius,

Mads Mikkelsen – Draco.

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

Sequel: Wrath of the Titans, dir. Jonathan Liebesman, Warner Bros. Pictures, 2012.

Summary

A remake of the 1981 film of the same name (also surveyed on this database), this film loosely follows both the plot of the original film and the myth of Perseus and Medusa.

The film opens with the story of the defeat of the Titans by the Olympians. After Hades has produced the Kraken, the Titans are defeated and Zeus, Poseidon and Hades assigned kingdoms. Zeus creates humans to fuel the gods with prayers, and the voiceover explains that humans are questioning and rising up against the gods.

In the next scene, Perseus and the dead Danaë are pulled from the sea in a casket by a fisherman and his wife, who raise Perseus. Twelve years later, Perseus and his family are sailing into the harbour at Argos when soldiers pull down a huge statue of Zeus, which crashes into the sea. Hades appears, sends Furies to attacks the soldiers and destroys the family's boat, drowning Perseus's family. On Olympus, the gods demand Zeus ends the fighting with mortals. Zeus refuses. Hades appears and Zeus asks Hades to turn humans on each other.

In Argos, Perseus has been rescued and brought to the city. At the palace, king Cepheus and queen Cassiopeia praise the bravery of their few surviving soldiers for striking at Zeus. Princess Andromeda admonishes her parents for provoking the gods. Cassiopeia insists that the gods need them, and then compares Andromeda's beauty to that of Aphrodite. As Andromeda tries to stop her, Cassiopeia continues, so Hades appears and attacks the surviving soldiers, sparing Perseus after apparently recognising him. Perseus makes for a sword to attack Hades, but is stopped by a mysterious woman. Hades kills Cassiopeia by rapidly aging her, and tells the court that the Kraken will destroy the city in ten days unless they sacrifice Andromeda to it, then reveals to Perseus that he is the son of Zeus. On Olympus, Zeus is told about Perseus, but refuses to help him on the basis that he has never heard his prayers.

In Argos, king Cepheus asks for Perseus' help defeating the Kraken as he is a son of Zeus. Rejecting his divinity, Perseus insists he is just a man and is imprisoned. The mysterious woman, revealing her identity as Io, visits him and tells him the story of his birth: that king Acrisius sieged Olympus and to humiliate him, Zeus slept with his wife, Danaë. Discovering them together, Acrisius executes Danaë and her son by Zeus, Perseus, by throwing them into the sea. Zeus punishes Acrisius by striking him with lightning, disfiguring him. Io tells Perseus that if he defeats the Kraken he will be able to attack Hades. Perseus and the king's guards head out to see the Stygian witches to find out how to kill the Kraken, followed by Io.

Hades visits Acrisius, now calling himself Calibos, in a dungeon. Hades sends him to kill Perseus. While on their way to the witches, Perseus finds a sword in a glade. One of the guards, Draco, tells him it is a gift from the gods, so Perseus refuses it. Wandering off, Perseus finds a herd of flying horses, the Pegasus. As the men search for Perseus, they are attacked by Calibos. Perseus fights Calibos, who bites him and is then forced to flee when Draco cuts off his hand. The hand and the drops of blood from the stump become massive scorpions. They are almost overcome when strange creatures called Djinn tame the remaining scorpions and save them. Perseus passes out from the venom in Calibos' bite, but refuses to pray for relief. The Djinn heal Perseus. Draco rebukes Perseus for refusing divine help, but Perseus says again that he wants to carry out the quest as a man.

The Djinn have trained the scorpions so the party rides them to the garden of Stygia. The witches tell them they need the head of Medusa. Zeus appears to Perseus and asks him to live as a god, or he will die on his quest. Perseus refuses. Perseus asks the remaining men for their help, and they travel to the Underworld to find Medusa's temple. When they get there, Io is not allowed inside as she is a woman. The men enter and are picked off by Medusa until only Perseus is left. Using the reflection in his shield, Perseus cuts off her head. Outside the temple he reunites with Io, who is immediately killed by Calibos. Perseus fights and kills Calibos, who turns back into Acrisius as he dies. The dying Io tells Perseus to hurry to Argos. A Pegasus appears and Perseus flies to Argos.

On Olympus, Zeus orders the Kraken to be released. In Argos, Andromeda is ready to be sacrificed. Back on Olympus, Hades reveals that he has been feeding on the fear of humans while Zeus grows weak from lack of prayers. Meanwhile, Perseus has reached Argos. Hades appears and sends the Furies to attack him. Eventually, Perseus destroys the Kraken with Medusa's head, which he then throws into the sea. Andromeda falls into the sea. Hades mocks Perseus who throws his sword at him, wounding him. Perseus rescues Andromeda, and they are washed up on the shore. Andromeda asks Perseus to be her king, and Perseus declines, riding off on Pegasus. Zeus appears to Perseus, and Perseus complains that Hades is still alive. Zeus tells him that Hades' strength is up to humans. Zeus claims Perseus as a son and asks him again to come to Olympus; when Perseus refuses, Zeus restores Io to life.

Analysis

Like the earlier film, this film freely adapts the myth of Perseus and Medusa and includes references to other myths and cultures. The storyline reveals the heavy reliance on the 1981 version of the film as opposed to ancient sources, moving away from ancient Greek versions of the myth where it deviates from the earlier film rather than towards them. However, unlike the original film, the geography and cultural context of this version is tightly focused on Greece. Some of the newly introduced figures and stories include Io, who is imported from a different Greek myth as Perseus' mentor and love interest; the Djinn, from Arabic and Islamic mythology; and Hades, who in ancient versions of the myth is not involved, but here is the primary antagonist. As in the 1981 film, the narrative of the myth is flipped to see Perseus retrieving the head of Medusa in order to save Andromeda, although his primary motivation is to strike at the gods, Hades in particular. Calibos is brought back from the original film, but he is elided with Acrisius.

One of the clearest deviations from the 1981 Clash of the Titans and from similar films such as the 1963 Jason and the Argonauts is the move away from belief in and reliance on the gods. The film consciously moves away from the idea of the gods as able to easily manipulate humans via the chessboard in the earlier film.* In this film, Perseus is defined by his dogged unwillingness to accept his divine heritage or help from his father, Zeus, even when it puts him or his companions in danger. This is part of a wider movement towards the relatability of the mythic hero in film ,** and echoes other films from this period (for example, the 2014 Hercules and the 2011 Immortals). Perseus' refusal to accept divine aid does mean that (as in the earlier film) he receives mortal help from a band of warriors, again fueling the notion of the supremacy of humans over the gods. This is also suggested by Perseus' spurning of Andromeda in favour of Io. Some of the specific changes to the plot from the earlier film are in service of this focus on the inferiority of the gods, including the elision of Acrisius with Calibos, Calibos being a bitter version of Acrisius recruited by Hades; the change to Acrisius as the husband of Danaë, as a king waging war against the gods; and the inclusion of Io, as a character who has been cursed following the rejection of a god's sexual advances. Another small nod to this is the cameo by Bubo, the mechanical owl made by Hephaestus as a replacement for Athena's owl in the 1981 film; here, Perseus pulls the owl from a box of weaponry and is told to leave it by one of the soldiers.

While the film moves further away from ancient versions of Perseus' myth, it retains the hybridised references to other cultural mythology, most notably the Djinn, who are borrowed from the Middle East. Like the 1981 film, there is a reliance on Orientalism in the depictions of Eastern characters, including the Djinn and two brothers who accompany Perseus and the men from the palace: their appearances are accompanied by "Eastern" style music, and they the Djinn in particular are encountered in the desert. Both the brothers and the Djinn possess esoteric knowledge that is implied to originate from outside Greece.

In contrast to the earlier film, the gods are marked from mortals through their costumes, which are, for the most part, based on armour; this is in keeping with contemporary representations of Greek gods on screen but was also inspired by Japanese manga.*** The notable exception to this is Hades, although his costume of a ragged black cloak is reflective of him as evil and underhanded - both the colour and quality of his costume are visual shorthand for bad character. This itself illustrates a move away from ancient depictions of the gods, as Hades is not considered "evil" in ancient Greek versions of the mythology, and he is also associated with wealth, not an aspect that comes across in his costume. Joanna Paul notes that the shift from the physical effects of the 1981 film to CGI technology allows for more spectacular appearances of the gods.**** One of the key concerns of the gods in the film is the dwindling worship among mortals, and thus there is a shift also in the role of the gods as compared to the 1981 film. Here, the gods are needy and selfish, and they seem unable or unwilling to engage with mortals. For example, when Zeus first discovers that Perseus is his son, he declares that as Perseus has never prayed to him, he will not give him any aid.

The central story of the death of Medusa is dealt with relatively closely to ancient versions of the myth: Io relates to Perseus that Medusa was transformed by Athena into a terrible monster after being raped by Poseidon. The film is modern in its approach to gender, largely ignoring historical gender norms, with Andromeda an independent princess concerned with the welfare of her people and Io accompanying Perseus all the way to Medusa’s temple; however, the goddesses are conspicuously silent in comparison to the earlier film. Io declares that as a woman, she is not allowed in the temple, and it is unclear whether this has been imposed by Athena or is Medusa's own choice so as to punish men. Io's own story - of being cursed with agelessness after rejecting the advances of a god - provides an early indication of Medusa's fate. Zeus' own transgressions, which include the rape of Danaë by explicit deception (his disguise as her husband) are not addressed, and neither is Poseidon's responsibility for Medusa. In this remake, Medusa is of the beautiful type, playing on femme-fatale stereotypes rather than the monster of the 1981 film. However, she does retain her snake tail and her bow and arrows, keeping her link with the Amazons whilst not masculinising her like the earlier Medusa.

In terms of viewer reception, the film is suitable for older children although shifts from a family-friendly film to a more mature action adventure. The changes to the mythology generally mean that viewers do not require a knowledge of the story before watching, as the terms of the film's mythology are explained within it. Like the earlier film, there is a clear undercurrent of social norms being maintained, which are in keeping with the contemporary social settings of the audience - thus, the secularism and individualism of western countries is paralleled by the film, at the cost of engagement with the source material which favours divine intervention, kinship, and patriarchal supremacy.

* Paul, Joanna, Film and the Classical Epic Tradition, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, 119.

** Raucci, Stacie, "Of Marketing and Men: Making the Cinematic Greek Hero, 2010–2014", in Monica Cyrino, Meredith Safran, eds., Classical Myth on Screen, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, 166–169.

*** Maurice, Lisa, Screening Divinity, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019, 75.

**** Paul, Joanna, Film and the Classical Epic Tradition, op. cit., 119.

Further Reading

Maurice, Lisa, Screening Divinity, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019.

Paul, Joanna, Film and the Classical Epic Tradition, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Raucci, Stacie, "Of Marketing and Men: Making the Cinematic Greek Hero, 2010–2014", in Monica Cyrino, Meredith Safran, eds., Classical Myth on Screen, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, 161–172.