Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Jerzy Drzewiecki, Syn wyzwoleńca. Żywot Quintusa Horatiusa Flaccusa. Lwów: Nakładem Filomaty, Lwów, Uniwersytet, 1935, 56 pp.

ISBN

Available Onllne

Syn wyzwoleńca at Polona.pl (accessed: May 6, 2022).

Genre

Biographies

Short stories

Target Audience

Children (10–13 )

Cover

Cover available at Polona (accessed: May 6, 2022). Public domain.

Author of the Entry:

Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Cover retrieved from Polona (accessed: May 6, 2022). Public domain.

Biblioteczka Filomaty (Publisher)

Biblioteczka Filomaty [The Little Library of "Filomata"] was a series of short monographs written by scholars for school children on various ancient themes (often biographies of ancient authors and figures, in the form of novellas or short stories) designed to inspire young people to study Antiquity. Most of the volumes were designated by the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Public Education as appropriate for children 11 to 13 years old. The series was initiated in 1934 by the editor of the quarterly Filomata (accessed: May 6, 2022) and published in Lwów (now Lviv) by the University Press. Publication of Biblioteczka Filomaty was restarted after WW2 and continued until 1965.

Filomata was published between 1929 and 1939 in Lwów and resumed in 1957–1996 in Kraków. The periodical, entitled after Greek φιλομαθία – “passion for knowledge”, was founded and edited by Ryszard Ganszyniec (changed in 1949 to Gansiniec) and after his death in 1958, for over 30 years by his wife Zofia Gansiniec, a classical philologist, ancient historian, and archaeologist. The editors stated that the first issue was aimed at high school students.* Inside, many papers were written by the most eminent scholars of the humanities. The profile of the periodical changed after the war, targeting university students and scholars; Filomata became focused on ancient culture and its reception: literature, language, history, and archaeology.

The series Biblioteczka Filomaty before 1939 contained:

- Lewicki, Tadeusz Marian, Z nad Tybru i z nad Ilissu:

- O triumfie rzymskim (accessed: May 6, 2022).

- W szkole atheńskiej (accesed: May 6, 2022).

- O widowiskach rzymskich (accessed: May 6, 2022).

- Rocznica urodzin w domu magnata rzymskiego (accessed: May 6, 2022).

- Rzymianin na ateńskiej akropoli

- Wysłannik króla Pyrrhosa w Rzymie

- Z dni klęsk i chwały (Salamina)

- Wywczasy poety (Horatius), part I, part II, part III, part IV (accessed: May 6, 2022).

- Bourget, Paul, Dobosz, trans. Oktawia Cybulska-Opolska.

- Krzemicka, Irena, Powrót Odyssa.

- Schulbaumówna, Zofia, Aspasia (accessed: May 6, 2022).

- Krzemicka, Irena, Pieśniarz życia, Hesiodos.

- Barbaszowa, Marja, Cornelia, matka Gracchów.

- Goldberger, Stanisław, Prawo rzymskie.

- Ganszyniec, Ryszard, Dzieje naszego abecadła.

- Schenkelbachówna, Halina, Agrippina, matka Nerona (accessed: May 6, 2022).

- Schulbaumówna, Zofia and Artur Rapaport, Xenophon. Żołnierz – historyk.

- Press, Izydor, Od alchemji do chemji.

- Sandauer, Artur, Theokritos, twórca sielanki.

- Sadowska, Stefanja, Diocletianus. Organizator państwa.

- Biliński, Bronisław, Hannibal, wódz karthagiński.

- Barbaszowa, Maria, Vestalka.

- Schulbaumówna, Zofia, Kleopatra.

- Pilch, Stanisław, Tacitus. Historyk cesarstwa (accessed: May 6, 2022).

- Krzemicka, Irena, O gród Ilionu.

- Czuprówna, Janina, Pindaros, piewca olympioników (accessed: May 6, 2022).

- Swieżawski, Stefan, Boëthius, ostatni Rzymianin.

- Stocka, Irena, Odkrycie Troi i świata Homera.

- Drzewiecki, Jerzy, Syn wyzwoleńca (accessed: May 6, 2022).

- Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Wybór poezji (accessed: May 6, 2022).

- Wąsowicz, Janina, Hippokrates i medycyna starożytna.

- Macaulay, Thomas Babington, Pieśni starorzymskie, trans. Paulina Klarfeldówna.

- Srebrny, Stefan, Co zawdzięczmy kulturze starożytnej.

- Kaczkowski, Stanisław, Na nutę Horacego (accessed: May 6, 2022).

- Hospodarewska, Joanna, Kuchnia starożytna.

- Dąmbska, Izydora, Platon.

- Ganszyniec, Ryszard, Metryka klasyczna.

- Lechicki, Czesław, M. Porcius Cato Starszy.

- Moraczewska, K, Bajka w starożytności.

- Ganszyniec, Ryszard, Wymowa łaciny.

The contents of the series are based on: Spis wydawnictw Filomaty oraz Spis rzeczy do Filomaty 1–83, Lwów: Administracja Filomaty, Lwów Uniwersytet, 1937, 23–24.

Available at: obc.opole.pl (accessed: May 6, 2022).

* Ryszard Ganszyniec, “List redaktora do filomaty”, Filomata 1 (1929): 46–48.

Prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Jerzy Drzewiecki (Author)

Two people with this name were found, both quite unlikely candidates: a construction engineer 1878–1964 and an aircraft designer 1902–1990. If anyone can assist in identifying this author, please contact marta.pszczolinska@gmail.com

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

See: Biblioteczka Filomaty.

Summary

Little Quintus lives in Venusia, in rural Apulia, on the southern Adriatic shore (on the heel of the boot-shaped Italian peninsula). His father, a freedman, decides to choose a school for him in Rome where nobody knows him and where he would be spared mocking or bullying because of his father’s origin, which would be unavoidable at a local school. The boy is very excited and grateful to him. In Rome, despite the harsh educational methods favoured by his teacher, Orbilius, Quintus wants to study hard to become a priest of the Muses.

Years later, in 44 BC, he studies in Athens, and with his fellow students, he discusses various philosophical questions about life and later about the war that is coming upon them. Having heard that Brutus, one of Caesar’s assassins, came to Athens, the students decide to join his forces as defenders of the Roman Republic.

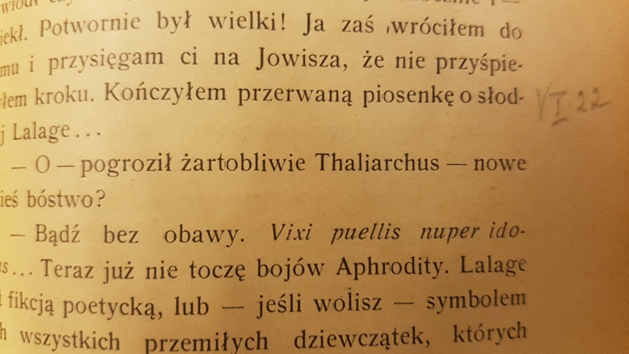

Young Horace deserts the battlefield of Philippi, his father dies, and his country estate is gone. He arrives in Rome, where he has to work as a scribe to make ends meet. One day, Rufus, an old friend met in the City by chance, introduces him to Virgil, who – impressed by his talent – intends to bring Horace to Maecenas’ circle. Despite an unfortunate first impression, Horace is given a second opportunity months later. He presents his Satires to Maecenas, who, amazed by the poems, invites him to Sabinum, where he had just bought an estate. Horace likes the rural life far away from politics in Sabinum. He is occasionally visited by friends, such as Thaliarchus, to whom he presents tablets with a new poem.

Horace visits Maecenas and Virgil in Rome. Caesar Augustus, tired by the duties of the high office, comes to spend time with them. They discuss poetry and listen to recitations. Horace and Virgil return home and have their final conversation before Virgil leaves for Greece. Virgil confesses that he would rather destroy the Aeneid than leave it unfinished. They say their goodbyes, not knowing it is the last time they see each other. The final scene shows the poet sitting in the moonlight on the base of a statue, writing Exegi monumentum.

Analysis

The booklet was published in an educational series aimed at 10 to 13 year old school students. In the 1930s, children in that age range would typically be familiar with some Latin (Latin was taught for 4 years in the secondary school curriculum). Students could extend school learning by the voluntary reading of the series. This particular booklet describes the life of Horace based on the clever use of direct or paraphrased quotations from the poet’s works.

As the book is aimed at school students, the author starts with Horace’s childhood and younger years. The future poet is presented as a brave boy who is not scared of a mythical forest and the creatures his nanny tells him about. On the contrary, he likes playing in the actual forest, loves nature and often uses poetic language to describe ordinary things, unusual behaviour for a child of his age. His father notices his talent and decides to educate him as best as he can afford. This decision defies the opinion commonly held in his village – that poets are slobs. The boy appreciates the value of an education and tries to be diligent, desiring to become as knowledgeable as his master Orbilius. During a debate with his friends in Athens, the young Horace appears to be a sensitive person who loves life and appreciates having friends and admiring beauty in all its aspects. He adores Greece, the Apulian mountains, the stars, wine, roses, music, songs and poetry. He also loves Rome, so he is against civil war and bloodshed. His pacifism is misunderstood by his companion Cicero (the famous Orator’s son) who opts for military solutions. He offends Horace with harsh words and calls him a freedman and a coward. Despite his rejection of saving the Republic at the high price of committing murder and starting a civil war, young Horace cannot refuse to join Brutus’ forces. Later on, however, as a young adult, he is more assertive. At first, he declines an introduction to Maecenas that could launch his career as a poet through political and societal connections. He prefers to be poor but independent. Fortunately, he comes to his senses (and even makes friends with Maecenas) while still appearing like a man who appreciates negotium and celebrates the simplicity of modest life. In Sabinum, his poetry flourishes as he lives the life which makes him happy.

Horace is intrigued by Virgil – a timid, shy and modest man who dislikes crowds, being the object of attention and is uncomfortable with his popularity. He lives in a simple, rural villa. As for poetry, being a perfectionist, he prefers not to share his work with his friends and insists on polishing each line and every word before presenting it to the public. At the same time, he is sensitive to the beauty of Horace’s poetry and sees its remarkable value. Without feeling envious, he wants to help Horace develop his talent.

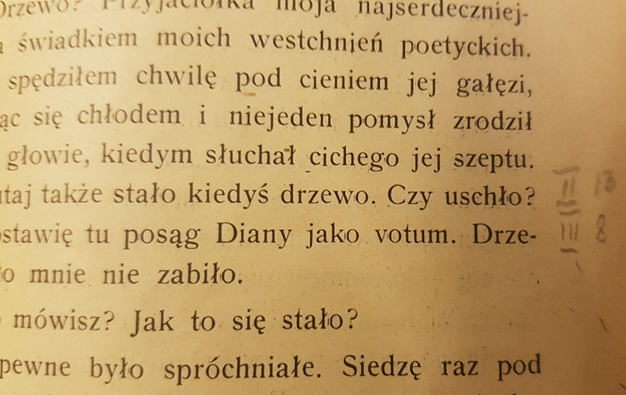

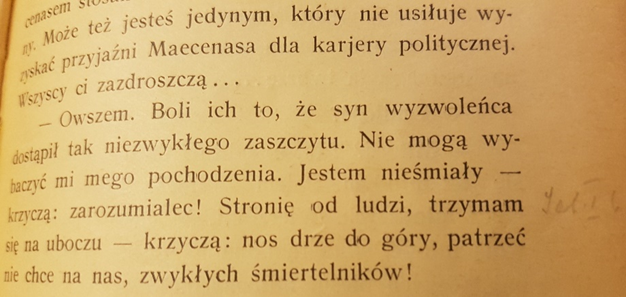

Drzewiecki tries to use the actual Horatian language as much as possible. He alludes to the most recognizable fragments of Horace’s poetry in many phrases, sentences, and descriptions. In addition, some quotations or entire short poems are cited in translation or the original Latin. It seems particularly relevant for students who have read Horace at school and would recognize them and find satisfaction from identifying the source. The entire chapter In Sabinum adopts this technique. It describes a day spent with Thalliarchus and contains not only the motif of snow-white Soracte or sweet Lalage but is full of allusions to various odes and epodes. This device was effective, as in the copy I was using, a diligent hand wrote in the margin references to particular poems (see addenda). Drzewiecki also used a touching image of self-fulfillment and accomplishment of youthful promises. On his first day in Rome, Horace sees the priestess ascending the stairs of Capitolium accompanied by the pontifex maximus, both of whom he considered divine. When he realizes that they are priests and not gods, he vows to become a priest of the Muses. In the final scene, Horace writes the ode I.30 – Exegi monumentum – evoking that scene remembered from childhood. The poet fulfills his childhood dream by composing poetry that survives eternally.

This booklet has a didactic purpose. Its readers learn that if dreams are followed by hard work at school and in life, they transform into obtainable goals. Despite Horace’s humble social originsand lack of money, his talent, diligence and persistence allowed him to achieve greatness. If he was successful, there is hope for others.

Further Reading

Armstrong, David, Horace, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1989.

Hills, Philip, Horace, Bristol Classical Press, 2005.

Horace, Satires, Epistles and Ars Poetica, trans. H. Tuston Fairclough, London: William Heinemann and New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1926 (accessed: May 6, 2022).

Pawlak, Małgorzata and Konrad Sanojca, "Misja edukacyjna krakowskich i lwowskich filologów klasycznych na łamach prasy specjalistycznej (1918–1939)”, Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Prace Historyczne 145.2 (2018): 257–270 (accessed: May 6, 2022).

Addenda

Notes in the margins with references to particular poems. By unknown reader. Scans Marta Pszczolińska.