Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Filippos Mandilaras, Ο Περικλής και ο Χρυσός Αιώνας [O Periklī́s kai o Chrysós Aiṓnas], My First History [Η Πρώτη μου Ιστορία (Ī prṓtī mou Istoría)] (Series). Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2011, 36 pp.

ISBN

Available Onllne

Demo of 9 pages available at epbooks.gr (accessed: October 13, 2021).

Genre

Instructional and educational works

Mythological fiction

Myths

Target Audience

Children (age 5+)

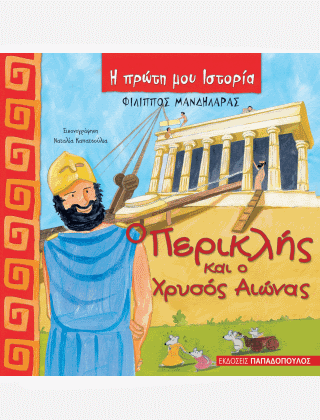

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher. Retrieved from epbooks.gr(accessed: July 5, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roeampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Hanna Paulouskaya, University of Warsaw, hannapa@al.uw.edu.pl

Natalia Kapatsoulia (Illustrator)

Natalia Kapatsoulia studied French Literature in Athens, and she worked as a language tutor before embarking on a career as a full-time illustrator of children’s books. Kapatsoulia has authored one picture book Η Μαμά πετάει [Mom Wants to Fly], which has been translated into Spanish Mamá quiere volar. Kapatsoulia, who now lives on the island of Kefalonia, Greece, has collaborated with Filippos Mandilaras on multiple book projects.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Profile at the epbooks.gr (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Filippos Mandilaras

, b. 1965

(Author)

Filippos Mandilaras is a prolific and well-known writer of children’s illustrated books and of young adults’ novels. Mandilaras studied French Literature in Sorbonne, Paris. His latest novel, which was published in May 2016, is entitled Υπέροχος Κόσμος [Wonderful World], and it recounts the story of teenage life in a deprived Athenian district. With his illustrated books, Mandilaras aims to encourage parents and teachers to improvise by adding words when reading stories to children. Mandilaras is interested in the anthropology of extraordinary creatures and his forthcoming work is about Modern Greek Mythologies.

Sources:

In Greek:

Profile on EP Books' website (accessed: June 27, 2018).

i-read.i-teen.gr (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Public Blog, published 15 September 2015 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Press Publica, published 28 January 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Linkedin.com, published published 6 May 2016 (accessed: February 6, 2019).

In English:

Amazon.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

On Mandoulides' website, published 7 March 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

In German:

literaturfestival.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Summary

The purpose of this book is to showcase Pericles’ life, from childhood to death, and the politics and warfare during Athens’ “Golden Age”, as noted in the subtitle. The front cover shows a helmeted and bearded Pericles before his major construction project, the Parthenon. Builders are shown carrying a Doric capital for the façade’s eighth column, which is missing from the incomplete temple. Yet, we are not only in ancient Athens. At the bottom of the cover, a group of moving mice allude to popular folklore characters, and to more recent, albeit unspecified, timeframes.

On the inside cover, appropriately for a book about a historical and not a mythological figure, we are given dates (495–429 BC) for Pericles’ life. On the first page, Mandilaras’ rhyming verses summarise the statesman’s achievements. Next, children learn keywords, such as “orator,” “general,” and “city” (ρήτορας, στρατηγός, and πόλη in Greek), all of which accurately describe what Pericles stood for in antiquity.

On the next page (no number is given), the story starts from the beginning. First, we see Pericles’ rich parents, Xanthippos and Agariste. Pericles is a conscientious pupil, doing his maths, dictation, philosophy, and music and excelling in rhetoric as a child.

The Persian attacks had left Athens with many buildings in ruins. On the walls of these ruins, we read, “Down with the Persians” in red, as if this were contemporary activists’ graffiti.

Mandilaras and Kapatsoulia explain democracy as follows. The text says that all citizens were equal, and the illustration shows, ingeniously, men at different steps all having the same height against a vertical scale. But, remarkably, Pericles, who comes from an aristocratic family, will join the Democrats, the party supported by farmers and labourers. The paradox is talked about in Athens. Mandilaras uses colloquial expressions: Τα ’μαθες για τον Περικλή? [Did you hear that about Pericles?].

Then, we are introduced to the practice of ostracism and how Pericles managed to ostracise his opponent, Kimon. Ephialtes is found dead, shown lying on the floor, engulfed by standing people so that his dead body is hardly visible. Pericles becomes the leader of the Democrats. Action is very swift, and we seem to have a happy ending at this stage. Pericles, in love, is shown walking with his second wife, Aspasia, whom he trusts more than anyone.

Pericles gives more power to the people and embarks on his building programme, alongside the architects Iktinos, Kallikrates, and Mnesikles and the sculptor Pheidias. While the building projects progress, Pericles’ enemies accuse him of all kinds of things. So we have tension building up. Next, Sparta and her allies attack and burn down the countryside of Attica. Pericles gathers the people inside the City Walls, wanting to protect them. The following year, however, a terrible plague comes, and Pericles, too, becomes ill and dies. And yet, Pericles’ legacy lives on, and Pericles becomes a model for other leaders.

The book closes with a section entitled “I learn more”, where the author gives information about the Golden Age, Pericles’ great works, and the Peloponnesian War. The children are asked to imagine what Pericles, his sculptor, and his architects would say if they were to visit modern Athens. Finally, children are asked to write how they would beautify their city and neighbourhood with public buildings if they had Pericles’ power.

Analysis

Instead of dry historical facts, we have a story that recalls myth or folklore. There is also a collapse of timescales because elements of the illustration, such as the red garments and red interior walls, do not recall a Greek past but a Roman one. The Romans wore red togas and red adorned Pompeian houses’ walls.

Modernity is valorised excessively in this book. The picture on the first page (unnumbered) shows Pericles emerging from behind one of the Caryatids and saying “Hello” (“ΤΣΑ!” in Greek) as if he played the contemporary game hide-and-seek. There is a three-bar sigma for “ΤΣΑ!,” which is epigraphically correct for fifth-century Athens. Pericles’ schooling may have a layer of modern stereotyping, with connotations of a link between an upper-middle-class background and a good education that enables him to be influential with words. Young Pericles is depicted walking through the streets of Athens while holding his parents’ hands. We form the impression of a modern nuclear family, with both parents contributing equally to a child’s upbringing. With graffiti on ruins, we have a subtle reference to urban life. The two Athenian political parties, the Oligarchs and the Democrats, include women in their members, reflecting a modern rather than ancient reality. Two red hearts appear between Pericles and Aspasia as they walk together. The image here recalls comics. More importantly, a modern parallel could be made with happiness in both one’s professional and personal life.

On the page where we read about Pericles’ death, we see a tourist before a souvenir shop with commercial models of the Parthenon and of Pericles’ busts. Any sadness relating to the loss of Pericles is softened by the smiley tourist and, more importantly, by a return to contemporary city life. Tourists are an integral part of Athens’ liveliness. The past and the present are nicely intertwined here. The tourist, moreover, is a young girl with red hair and glasses, making other foreigners, and surely not the average dark-haired south Mediterranean person, feel included in the visual narrative. Subtly, Pericles’ legacy, reflected in the souvenirs, is offered to the world, to a vast community of foreign visitors to Athens. Thus, Pericles’ legacy has become international and not exclusively, if at all, Greek.

Further Reading

Information about the book at epbooks.gr, published September 20, 2011 (accessed: August 1, 2018).