Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Jan Parandowski, "Rzym. Od królów do cesarzy", Dookoła świata 36 (1957): 14–15.

Genre

Article in a periodical*

Essays

Target Audience

Crossover (Schoolchildren, teenagers, young adults)

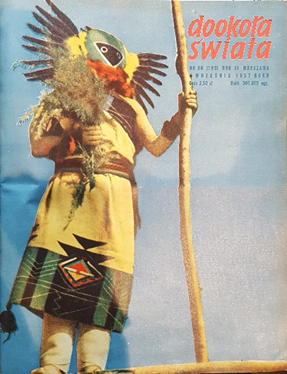

Cover

Cover with kind permission of the copyright holder for the magazine Dookoła Świata (1954–1976).

Author of the Entry:

Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Photograph by Edward Hartwig, retrieved from the National Digital Archives.

Jan Parandowski

, 1895 - 1978

(Author)

Classical philologist and archaeologist. An outstanding and prolific author of books related to Antiquity; translator of classical masterpieces. Contributed to many Polish newspapers and magazines. Chairman of the Polish PEN Club from 1933 to 1978. Recipient of prizes for outstanding literary achievements, such as a bronze medal received at the 1936 Berlin Summer Olympics for his book Dysk olimpijski [Olympic Discus]. Member of the European Society of Culture. In 1962 he was elected Vice-President of the International PEN. An exceptionally successful supporter and advocate of Classical Antiquity in Poland. His Mitologia. Wierzenia i podania Greków i Rzymian [Mythology. Beliefs and Legends of the Greeks and Romans], still often read even in primary school, remains for many generations of Polish readers a fundamental source of the knowledge of ancient myths.

Major works: Eros na Olimpie [Eros on the Olympus], 1924, Mitologia. Wierzenia i podania Greków i Rzymian [Mythology. Beliefs and Legends of the Greeks and Romans], 1924; Wojna trojańska [Trojan War], 1927; Oscar Wilde’s biography Król życia [A King of Life], 1930; Dysk olimpijski [Olympic Discus], 1933; Niebo w płomieniach [Heaven in Flames], 1936; Trzy znaki zodiaku [Three Signs of the Zodiac], 1938; Godzina śródziemnomorska [The Mediterranean Hour], 1949; a study on creative writing Alchemia słowa [Alchemy of the Word], 1951. He also translated into Polish Caesar’s Civil War, 1951, and Homer’s Odyssey, 1953.

Sources:

Krełowska, Danuta, Jan Parandowski: życie i twórczość, Toruń: Wojewódzka Biblioteka Publiczna i Książnica Miejska im. M. Kopernika, 1989.

Paciorkowska, Monika, Jan Parandowski, slideshare.net (accessed: December 30, 2020).

"Parandowski Jan", in Jadwiga Czachowska and Alicja Szałagan, eds., Współcześni polscy pisarze i badacze literatury. Słownik biobibliograficzny, vol. 6: N–P, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 1999, 254–260.

"Parandowski, Jan", in Encyklopedia PWN, encyklopedia.pwn.pl (accessed: December 30, 2020).

wikipedia.org (accessed: December 30, 2020).

Życiorys Jana Parandowskiego, kul.pl (accessed: December 30, 2020).

Bio prepared by Joanna Grzeszczuk, University of Warsaw, joannagrzeszczuk1@gmail.com

Summary

The weekly Dookoła świata [Around the World] (1954–1976) was intended to be a kind of a travel magazine and “a window to the external world” for Polish teens in Polish People’s Republic times – see here [entry “Z antycznego świata”, Dookoła Świata 13 (1957)].

The article is illustrated with a large photograph of the Augustus of Prima Porta statue from Braccio Nuovo of the Vatican Museums and small images of the Capitoline she-wolf between particular paragraphs.

Parandowski’s text starts with a parallel between Rome and an oak tree (which, from a small acorn, becomes a massive and majestic tree) and describes Rome’s origins against the historical background. Next, the author briefly writes about the Etruscans and what Rome owed them. The following paragraphs are focused on Roman citizens, their role models, social position and potential hardships, depending on who they were and where they lived. Then the reader can learn about how extended the Roman territory was in its prosperous imperial era and how safe people from various ethnic groups could be within the Roman borders due to peace and the network of roads facilitating quick communication, tourism and trade, further simplified by a unified coinage system. The fact that the conquered peoples were allowed to keep their cultural and linguistic traditions is described, as well as the state governance and economic system with its pros and cons, including the institution of slavery. The last paragraph describes changes in Rome's appearance, organization and entertainment potential since the Augustan age.

Analysis

The article breaks the routine contents of the magazine, mainly focused on travel and interesting places and cultures outside of Poland. But, on the other hand, it can be treated as correspondence from Rome before it became the popular destination of the 20th century.

The short text is written like a textbook. Parandowski, well-known today for increasing awareness of classical Antiquity, highlights the most important aspects of Roman civilization, condensing them in one short press article. Such texts can be viewed as an attempt to supplement insufficient information about the Antiquity young people received at school or to reinforce and consolidate the image provided in school curricula.

What draws attention is the language, which is clear and picturesque but not free from terms of judgment and opinion. As an example of the Roman respect for conquered peoples, Parandowski compares Romans to Germans and Russians in partitioned Poland and to their “barbaric suppression/extermination of the native language and culture [Polish]” (p. 15).

The author explicitly states his opinion about the superiority of the imperial era of general prosperity in comparison to the republic. Still, he is aware that the empire was not perfect. As the main disadvantage of the imperial system, he mentions the privileging of the Roman citizen over the rest of the population and slavery, although he considers the empire still more benevolent and progressive than the republic.

The author’s attitude towards social issues seems curious. Parandowski writes about changes taking place in the 2nd century BC when the middle class disappeared, leaving “two hostile forces: the predatory wealth and the urban mob” (p. 15) unequal in their potential as the mob was concentrated in the area of the capital and “the greed of the ruling class affected the remotest peoples and lands” (p. 15) subjecting them to constant oppression. The vaguely Marxist terms used by Parandowski seem unsuitable to describe Roman Antiquity, but the reality of Poland in the 1950s, with its ever-present Communist censorship, might have required this sort of subterfuge.

Further Reading

Selected bibliography concerning Jan Parandowski’s work and life see here.

Frycie, Stanisław, “Czasopisma dla dzieci i młodzieży okresu powojennego (1945–1970)”, Kwartalnik Historii Prasy Polskiej 3 (1977), 49–73.

Harjan, George, “Jan Parandowski: A Contemporary Polish Humanist”, Books Abroad 34. 3 (1960): 223–226.

Waksmund, Ryszard, “Periodyki dziecięce w systemie prasy. Propozycje metodologiczne do badań nad czasopiśmiennictwem dla dzieci i młodzieży”, Litteraria vol. 14 (1982), 149–163.