Title of the work

Studio / Production Company

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Fantasia [The Pastoral Symphony episode]. Directed by James Algar, Samuel Armstrong, Ford Beebe, Norman Ferguson, Jim Handley, T. Hee, Wilfred Jackson, Hamilton Luske, Bill Roberts, Paul Satterfield, Ben Sharpsteen, music [for The Pastoral Symphony episode] by Ludwig van Beethoven, conducted by Leopold Stokowski. Culver City, CA: Walt Disney, 1940, 126 min.

Running time

Format

Date of the First DVD or VHS

Awards

Leopold Stokowski won an Academy Award (Honorary Award) for the music. The movie also won a Hugo Award for the Best Dramatic Presentation – Long Form

Genre

Animated films

Mythological fiction

Target Audience

Crossover

Cover

Logo for the Walt Disney film Fantasia (1940). Retrieved from Wikipedia, public domain (accessed: 4 July 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Anna Mik, University of Warsaw, anna.m.mik@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

James Algar (Director)

Samuel Armstrong (Director)

Ford Beebe (Adapter)

Walt Disney photographed by Boy Scouts of America (17 May 1946), available at the file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike (accessed: May 25, 2018).

Walt Disney

, 1901 - 1966

(Animator, Director, Producer)

Walt Disney is perhaps one of the most popular cultural icons of all time. He was a producer and businessman, rather than an animator, although he drew at the beginning of his career. He was not really an artist – more like an interpreter of the well-known books or motifs. His first big production was Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs released in 1937. This was also the first full-length animated feature film, which was a big success for the new company. After that, he made about 60 full-length movies, which opened the road for the later productions, after Disney’s death.

Disney had a vision of creating a perfect world for children, where they would feel especially happy. But, as is well known, there were some hidden meanings in his movies, theme, that can challenge the over-sweetened image of this pop-icon. Disney also created a several attraction parks, such as Walt Disney World in LA (Disneyland opened in 1955, Disney World in 1965) and Disneyland near Paris (opened in 1992). He won 26 Academy Awards, 3 Golden Globe Awards, and many more. He died leaving a changed world behind, where the name Disney will live forever.

Source:

Smith, Dave, ed., “Walt Disney” (entry); in Disney A to Z: The Official Encyclopedia, 4th ed., Glendale: Disney Books, 2015.

Bio prepared by Anna Mik, University of Warsaw, anna.m.mik@gmail.com

Norman Ferguson (Director)

Jim Handley (Director)

Thornton Hee [T. Hee] (Director)

Wilfred Jackson

, 1906 - 1988

(Animator, Director)

Wilfred Jackson was an American animator, director and producer. Fascinated by the art of “moving pictures”, he decided to approach Walt Disney and offer him to work for his company for free. As the time in business was difficult, Disney hired the young excentric who much later was hailed a Disney Legend. Apart from being an animator, he had a very useful skill: he knew how to perfectly synchronize sound and picture, a technique developed (among other productions) in several Fantasia sequences. After assisting Ub Iwerks (the legendary creator of Mickey Mouse), he got promoted and became a director/co-director of many classic Disney movies, such as: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Peter Pan or Sleeping Beauty. Poor health forced him to retire in 1961.

Source:

Smith, Dave, ed., “Wilfred Jackson” (entry); in Disney A to Z: The Official Encyclopedia, 4th ed., Glendale: Disney Books, 2015.

Bio prepared by Anna Mik, University of Warsaw, anna.m.mik@gmail.com

Hamilton Luske (Director)

Bill Roberts (Director)

Bill Satterfield (Director)

Ben Sharpsteen (Director)

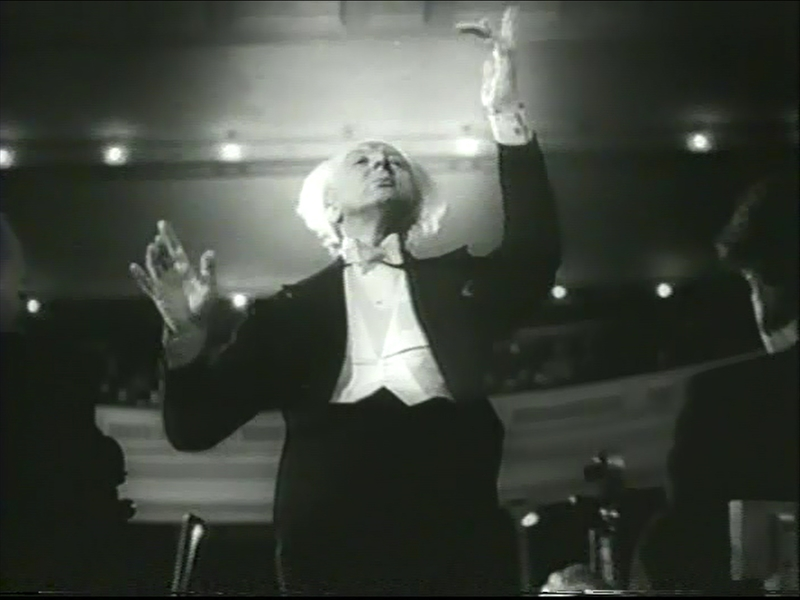

Portrait of Leopold Stokowski, photographed by United Artists / Federal Films (1947), the file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike (accessed: May 25, 2018).

Leopold Stokowski

, 1882 - 1997

(Director, Musician)

Leopold Stokowski was an American conductor, with Polish and Irish roots. For many years, he was a music director in many musical institutions, inter alia the Philadelphia Orchestra, which accompanied under his command the animated stories in Fantasia with classical music. For this production he won an Oscar. He was also a founder of the Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra and the American Symphony Orchestra. Stokowski was a music guest in Carnegie Hall (1947) and was a conductor in One Hundred Men and a Girl (1937).

Bio prepared by Anna Mik, University of Warsaw, anna.m.mik@gmail.com

Deems Taylor

, 1875 - 1966

(Composer)

Deems Taylor, “the dean of American music,” is well known as an American music critic and promoter of classical music. He agreed to comment on every episode and lead the narration, which was supposed to, and actually did, bear the prestige of the production. His live-action commentary is intertwined with the animated episodes.

Bio prepared by Anna Mik, University of Warsaw, anna.m.mik@gmail.com

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

Fantasia 2000 (sequel)

Summary

Fantasia is composed of 8 episodes, each based on a different piece of classical music:

- Toccata and Fugue in D Minor by Johann Sebastian Bach.

- Nutcracker Suite by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

- The Sorcerer's Apprentice by Paul Dukas.

- Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky.

- Intermission/Meet the Soundtrack:

- The Pastoral Symphony by Ludwig van Beethoven.

- Dance of the Hours by Amilcare Ponchielli.

- Night on Bald Mountain by Modest Mussorgsky and Ave Maria by Franz Schubert.

In a search for ancient motifs, only one episode will be discussed – the Pastoral Symphony. This opens with a depiction of the idyllic land of the Mount Olympus and its mythical life shown using Disney aesthetics. Child-like satyrs playing flutes and frolicking unicorns welcome the viewers to the pastel-hued world of ease and bliss, undisturbed by any representation of evil or danger. The custody over this playful group is exercised by Pegasus-parents who differ from the colourful children. The female is white, the male is black, and this colour-based distinction can be interpreted as a yin yang symbol of complementary but opposite forces. They seem to symbolize the adult and perfect form of life that potentially exists in the colourful and playful young.

The next scene draws our attention to the special event taking place near the Pegasus settlement. In the bushes, we meet creatures we are very unlikely to encounter in popular culture or just culture in general: centaurides. They are about to meet their future husbands and consummate their love in the nearby forest. There we meet Dionysus, drinking wine and dancing with the mythical creatures, possibly celebrating the Dionysia. The idyllic scene is interrupted by Zeus, who (possibly out of boredom) calls up storms, endangering the inhabitants of the mythical land.

Although the situation seems hopeless, at the end the sun comes out and the rainbow appears, called up by Iris. The young Pegasi and small Cupids slide off the rainbow, knowing that safety has returned.

Analysis

The Case of the Centaurides: Centaurides* appear to be rather shy and self-effacing; this is why I perceive their presence in Fantasia as special and very meaningful. The first centauride that we see, is the one emerging from the stream, where centaurides (for now showing only their upper human part, not yet covering their breasts) enjoy the fresh water. This might be seen as highlighting the symbolic connection between womanhood and water, the source of power for the centaurides. All of them are beautiful and graceful. Centaurides have different skin-colours, although the hues are strongly associated with the white skin color of real-life women. They are rather relaxed, as they are being pampered by cupids combing their hair and dressing them with flowers, and – what might be perceived as disturbing – live doves. This idyllic picture might be called their mythical spa, where they can relax, apply make-up and get ready for their male partners, who are coming to meet them quite soon.

As soon as one of the centaurs announces the arrival of the whole group, centaurides seem to be ready for what was described by Ovid: “love was equal: on the hills they roamed together, and together they would go back to their cave; […]” (Ovid, Metamorphoses 12. 210 ff., trans. E. J. Melville). They also are handsome, well-built, with different bright skin-colours. Centaurides present themselves to their partners, as if in a display during a fashion show. They are matched up by colours (blue with blue, red with red, etc.), which on one the hand highlights the Platonic concept of love, but on the other presents their relationships as based on race.

As soon as they all paired off, they move on to different dating-like activities: couples spend time together eating fruit straight from the tree, swinging in a swing, hugging, and generally enjoying one another’s company. But not all centaurides have found their match; some of them would not be even acknowledged as needing or deserving a happy ending.

Racism: After (almost) all centaurides meet their destiny, and end up with their loves, the real feast can finally begin. It is hard to claim, whether the feast was set to celebrate these happy endings, or – the other way around – namely that the matching of the magical creatures was set because gods needed an efficient and free-working force to worship them. Centaurs gathered grapes and prepared wine for Dionysus, who enters the scene drunk, with a horn, riding a donkey. He is accompanied by centaurides who are black-skinned with a zebra body (which underlines the racial differences) and who pour him wine and fan him, as slaves are supposed to do. They do not join the party, with dances and general celebration. At this stage of the story their role ends in a stereotypical depiction of black woman serving a white man.

But Disney did worse still: because of the criticisms he received, he needed to cut some scenes from the Pastoral Symphony episode. In the uncensored version of the so called Sunflower episode, we encounter a character that did not make it to the official version of the mythical story. Sunflower (the name underlines the racial difference** between her, and the rest of the centaurides whose flowers are roses, daisies, etc.), a black-skinned centauride, with stereotypically drawn face and rings in her ears (and also with the body of a “black horse”), appears in this segment as a slave or servant of the “white” centaurides who await their future husbands. While the beautiful and graceful ladies are flirting with the arriving centaurs, Sunflower puts flowers in their tales and carries a floral veil after the clueless or maybe cruel “brides,” who do not seem even to notice her. In the next part, Sunflower – with a donkey – helps the drunk Dionysus to get to his throne.

These two last images could serve as a symbol representing the system of power in both the ancient and the American world. A fat, jolly man would be in the center of it, as a locus of the highest authority. The Black woman (as we can read the black-skinned centauride) is a servant who tries to show him the right way of getting to the spot from which he could rule. The horned Donkey appears indifferent to its role of an animal slave and in a patriarchal tandem with Sunflower pushes Dionysus. This reflects the way of keeping women (in this case especially African-American woman) and animals (the donkey – culturally assigned as a working animal) in their proper place by the contemporary American society and the creators of Fantasia. This movie was of course not an exception – as we can see in much later movies, such as instance in Good morning, Vietnam or of course in the Song of the South, to cite only Disney productions.

*It is hard to find the appropriate word for the female Centaur: some use “centauride,” others “centaurette.” I decided to use “centauride,” as it is closer to the Greek roots of the word.

** Sunflowers are known by a number of common names, one of them has racist connotations. See: Willetts, Kheli R., "Cannibals and Coons: Blackness in the Early days of Walt Disney" in Johnson Cheu, ed. Diversity in Disney Films: Critical Essays on Race, Ethnicity, Gender, Sexuality and Disability, Jefferson, London: McFarland& Company, 2013, 17.

Further Reading

Clague, Mark, "Playing in ‘Toon: Walt Disney’s “Fantasia” (1940) and the Imagineering of Classical Music", American Music 22.1 (2004): 91–109.

Haas, Robert, "Disney Does Dutch. Billy Bathgate and the Disneyfication of the Gangster Genre" in Elizabeth Bell. Lynda Haas and Laura Sells, eds., From Mouse to Mermaid. The Politics of Film, Gender and Culture, Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press, 1995.

Ovid, Metamorphoses, available at Theoi.com. (accessed: August 17, 2018).

Smith, Dave, ed., “Fantasia” (entry) in Disney A to Z: The Official Encyclopedia. 4th ed., Glendale, CA: Disney Books, 2015.

Willetts, Kheli R., "Cannibals and Coons: Blackness in the Early days of Walt Disney" in Johnson Cheu, ed., Diversity in Disney Films: Critical Essays on Race, Ethnicity, Gender, Sexuality and Disability, Jefferson, London: McFarland & Company, 2013, 9–22.

Addenda

– The Process:

In 1940, World War II was like a shadow cast over the United States of America. Although at the beginning most citizens were for staying neutral towards what was going on in Europe, the tension and subcutaneous fear seized the whole society. There was no actual military activity in the US during the late 1930s, but in 1941, the Pearl Harbor attack shook the nation and made it realize that the war indeed covered the whole world. A certain kind of worrisome atmosphere that was later put in different forms – also in forms of art – can be sensed in many products of American culture from that time. These later became a propaganda tool and part of a pro-war politics, that often took form of animation (examples are the Popeye from the Fleischer Studios fighting the Nazis or the Private Snafu).

Even if the production of such tv-shows engaged almost the whole of Hollywood, Walt Disney’s movies were certainly among most popular and influential (on famous example being Donald Duck fighting the Nazis). This might be due to the fact pointed out by Robert Haas: "Unhampered by the restrictions of early sound-filming procedures that often required actors to assume unnatural positions and cameras to remain stationary behind soundproof glass, Disney combined sound and image in an expressive manner impossible for live-action narrative cinema. Because Disney could fit visual action to dialogue and music, achieving perfect frame-by-frame synchronization, the product was immensely appealing to audiences of the late 1920s and early 1930s." (Haas 1995, p. 75)

After the success of releasing the first full-length animation in 1937 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Walt Disney realized that in order to keep the company successful, he needed to produce something rather special. His dream was to provide the audience with a unique experience for all – children and adults – by combining two types of art: classical music and animation. He was not a great specialist in either of these arts, but he was looking for new business solutions. As a result of his search, Walt Disney Productions released an experimental project in 1940 that he called Fantasia, consisting of seven animated episodes with a soundtrack by classical composers (Johann Sebastian Bach, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Paul Dukas, Igor Stravinsky, Ludwig van Beethoven, Amilcare Ponchielli and Modest Mussorgsky). According to Dave Smith, this movie is “one of the most highly regarded of the Disney classics”. (Smith 2015, p. 252)

Due to the production of Fantasia, a stereophonic sound reproduction system called Fantasound was developed.

– Box Office: Domestic Total Gross: $43,8500,000, Domestic Lifetime Gross: $76,408,097 (source: Box Office Mojo, link: www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=fantasia.htm).

– As far as links to the ancient tradition are concerned, we may point out the following motifs:

Direct connections to the characters from the Greek Mythology: gods Zeus and Dionysus,

Presentation of the Mythical Fauna: Centaurs, Pegasi, satyrs, cupids, etc.,

Settlement: at the foot of the Mount Olympus.

Characters: The Pastoral Symphony episode focuses on the conflict between Dionysus and Zeus. But in the whole chapter, we encounter various mythical creatures: pegasi, satires, cupids, centaurs, etc. At the foot of the Mount Olympus live a variety of species, resembling an animal sanctuary.