Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Filippos Mandilaras, Οι Ολυμπιακοί Αγώνες [Oi Olympiakoí Agṓnes], My First History [Η Πρώτη μου Ιστορία (Ī prṓtī mou Istoría)] (Series). Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2016, 36 pp.

ISBN

Available Onllne

Demo of 8 pages available at epbooks.gr (accessed: October 13, 2021)

Genre

Illustrated works

Instructional and educational works

Mythological fiction

Myths

Target Audience

Children (5+)

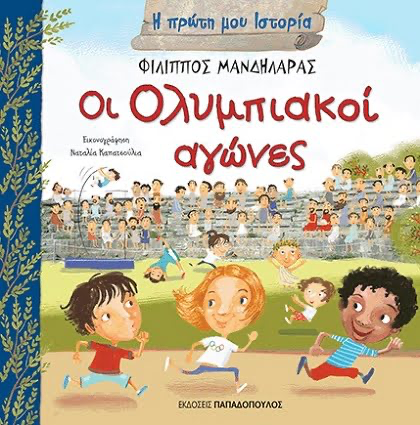

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher. Retrieved from epbooks.gr (accessed: July 5, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Dorota Mackenzie, University of Warsaw, dorota.mackenzie@gmail.com

Natalia Kapatsoulia (Illustrator)

Natalia Kapatsoulia studied French Literature in Athens, and she worked as a language tutor before embarking on a career as a full-time illustrator of children’s books. Kapatsoulia has authored one picture book Η Μαμά πετάει [Mom Wants to Fly], which has been translated into Spanish Mamá quiere volar. Kapatsoulia, who now lives on the island of Kefalonia, Greece, has collaborated with Filippos Mandilaras on multiple book projects.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Profile at the epbooks.gr (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Filippos Mandilaras

, b. 1965

(Author)

Filippos Mandilaras is a prolific and well-known writer of children’s illustrated books and of young adults’ novels. Mandilaras studied French Literature in Sorbonne, Paris. His latest novel, which was published in May 2016, is entitled Υπέροχος Κόσμος [Wonderful World], and it recounts the story of teenage life in a deprived Athenian district. With his illustrated books, Mandilaras aims to encourage parents and teachers to improvise by adding words when reading stories to children. Mandilaras is interested in the anthropology of extraordinary creatures and his forthcoming work is about Modern Greek Mythologies.

Sources:

In Greek:

Profile on EP Books' website (accessed: June 27, 2018).

i-read.i-teen.gr (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Public Blog, published 15 September 2015 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Press Publica, published 28 January 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Linkedin.com, published published 6 May 2016 (accessed: February 6, 2019).

In English:

Amazon.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

On Mandoulides' website, published 7 March 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

In German:

literaturfestival.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Summary

In this book, Mandilaras and Kapatsoulia chart the history of the Olympic Games. The origins of the Games are to be found in myth. According to the book, Heracles liked the location near the rivers Alpheus and Cladeus, and he decided to honour his father there. Hence, Heracles built an altar to Zeus and organised games at that place. We read that according to another version of the myth, the first Games were organised by Heracles Idaios, one of the Kouretes that kept company to infant Zeus. Yet another version has it that the Games were organised by Pelops to commemorate his victory over Oenomaus.

The conflicting stories about the first Games can be left aside. Iphitos, the King of Elis, asks the Pythia how people can have peace amongst them. The Pythia advises Iphitos to revive the Games, convinced that Heracles was indeed their founder. Iphitos follows her advice, but it will be many years before the first recorded Games take place in 776 BCE. Despite the summer heat, lots of people come to honour Zeus and to watch the Games. Many buildings are erected at Olympia, and Phidias produces a massive golden-ivory statue of Zeus.

The book continues by stating that, some twenty-five centuries ago, the Games ran as follows. The Hellanodikai, the judges of the Games, ensured that athletes competed on equal terms. Before the Games, there was a long procession and visitors from all over Greece camped by the rivers at Olympia. The Games lasted five days. There was a religious element, with a libation to Zeus on the first day and a sacrifice of one hundred oxen to Zeus on the fourth day. The athletic events took place on the second and third days. The winners were crowned on the fifth day. People talked fervently about Olympians, such as Theagenes of Thasos, Leonidas of Rhodes, Diagoras of Rhodes, but also about Kallipateira, the only woman who, dressed as a man, managed to attend the Games.

Mandilaras and Kapatsoulia end by showing how for one thousand years the Games brought peace and reconciliation. But then the Games stopped, and mud covered the site of Olympia. Only in 1894 there were serious talks about reviving the Games. We read about Baron Pierre de Coubertin and Demetrios Vikelas. The Games started again in 1896. Today, the Games take place every four years in different parts of the world. They start, nonetheless, at Olympia, with the ignition of the Olympic flame in the Temple of Hera. The book closes with a prayer to Zeus, asking him to grant peace “σε όλους τους λαούς της Γης” [to all nations on earth].

Analysis

While this informative account about the Olympic Games covers mostly ancient times, there is considerable emphasis on the Games’ legacy, especially on their potential to convey a message about peace, reconciliation, and friendship amongst people from all over the world. The book appears to be about world history, rather than just Greek history. For a book that falls under Papadopoulos Publications’ series My first History and not My first Mythology, Mandilaras and Kapatsoulia devote substantial attention to the Games’ mythical origins and religious significance. In the book The Twelve Gods of Olympus, we read about ancient religion only at the very end of the book.

The plot starts with quintessential mythical hero Heracles, who makes the location sacred. Alpheus and Cladeus are referred to as landscape features, and not as river gods. The world of the gods, nonetheless, is not very different from that of mortals. Heracles’ dedication to Zeus, inscribed on the altar, reads “Στον Δία τον Μπαμπάκα μου” [To Zeus, my sweet little father]. We are reminded, then, of the instinctual affection between a young child and a parent. Also, the demigod Heracles honours Zeus in the same way that mortals do, by using altars.

The three versions of the myth about the Games’ founder are perhaps likened to a competition, and we read that the Hellanodikai will decide which version holds true. Real people (the Hellanodikai) seem to interact with mythical characters (Heracles, Heracles Idaios, and Pelops). Iphitos consults the Pythia, like any king would do who went to an oracle for advice. The Pythia is convinced that Heracles had started the Games. Again, a real person, a priestess, believes strongly in myth, treating Heracles as a historical figure who had taken action in a specific place and also at a particular point in time. The myth can explain adequately how the Games were conceived. As a result, there is no marked transition between mythical and historical time. The date 776 BCE pertains to the first time when the Games were recorded, and not to when they started by Heracles or other mythical actors.

The information is exceptionally rich and varied. We learn, for example, about the art and archaeology of Olympia, the exclusion of women from the Games, the judges, the spondophoroi (messengers), the athletes, religious rites, what happened on each of the five days, and that the Games were celebrated for well over one thousand years. All this detail could create the impression, and with good reason, that the ancients’ veneration of the divine pervaded daily life. The procession two days before the Games has a religious and a fun component. We read in the illustration that the procession was an “εκδρομή” [excursion]. On the next page, we see people camping under the trees by a river and we read that this was a “πραγματική γιορτή” [real feast]. Also, it is implied that the ancients honoured, in different ways, both the gods and the athletes. The people who gathered at Olympia are equally fascinated with watching the sacrifice to Zeus and with watching the games at the stadion. Both religious and athletic events serve as spectacles that bring people together.

Zeus matters a great deal at Olympia. We learn that the Games are in his honour, Phidias sculpted a massive statue for him, and he receives libations and sacrifices during the Games. The happy people we see in the illustrations seem to have enjoyed the Games’ experience as a whole, including aspects of socialisation and gossiping.

One of the book’s main messages is about ethnic diversity. In antiquity, the Games reconciled enemies and the illustration here includes, ingeniously, an Egyptian, who presumably encapsulates a foreigner. In speech bubbles, spectators of the 1896 Athens Olympics admit that the Games offer an opportunity to get to know other people. Clearly, the Games are relevant to everyone in the modern world. This international (or globalising) outlook may explain why there is no reference to Greece’s national poet Kostis Palamas (1859–1943) who was greatly inspired by the Olympics*.

*See britannica.com (accessed: July 27, 2018).

Further Reading

Information about the book at epbooks.gr (accessed: July 27, 2018).

Addenda

From the series My First History.