Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Libby Gleeson, The Great Bear. Newtown, Sydney: Scholastic Australia Pty Ltd, 1999, 32 pp.

ISBN

Awards

Libby Gleeson:

Shortlisted for Children’s Book Council of Australia Picture Book of the Year Award in 2000; Bologna Ragazzi Award Fiction for Infants Category for The Great Bear in 2000.

Armin Greder:

Bologna Ragazzi Award for the illustrations of The Great Bear in 2000; Biennial of Illustrations Bratislavia Golden Apple Award in 2003; Nominated for the Hans Christian Anderson Award in 2004.

Genre

Fiction

Illustrated works

Mythological fiction

Picture books

Target Audience

Crossover (Children and Young adults)

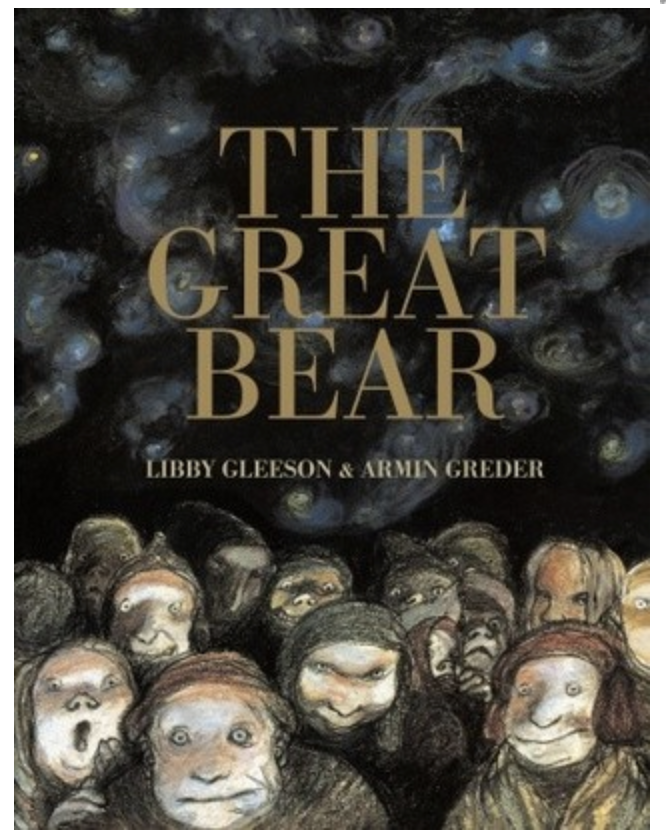

Cover

Courtesy of Walker Books Australia PTY LTD.

Author of the Entry:

Margaret Bromley, University of New England, mbromle5@une.edu.au and brom_ken@bigpond.net.au

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

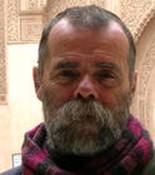

Courtesy of the Author.

Libby Gleeson

, b. 1950

(Author)

Author Libby Gleeson was born in Young, New South Wales, Australia, the third of six children. As a child she moved to other NSW country towns when their father, a school teacher, was transferred to Dubbo and Glen Innes. In country towns with no television she read a lot, with weekly visits to the public library. Gleeson studied history at university during the Vietnam War and the rise of the women’s movement. After gaining her Bachelor of Arts and Diploma of Education from the University of Sydney, she taught for two years at Picton, New South Wales. In 1976 she travelled for five years, teaching English in Italy and then London, where she continued to write her first novel, Eleanor Elizabeth, (1984) before returning to Australia to teach at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. She now writes full time.

Gleeson has a distinguished career as a writer of picture books, fiction for younger readers and young adults as well as non-fiction. Her works have been shortlisted for the Children’s Book Council of Australia awards. In 1997 she was awarded the Lady Cutler Award for Services to Children’s Literature.

Bio prepared by Margaret Bromley, University of New England, mbromle5@une.edu.au and brom_ken@bigpond.net

Courtesy of the Author.

Armin Greder

, b. 1942

(Illustrator)

Armin Greder was born in 1942 in Biel, Switzerland. Books and drawing played an important role from his early childhood. His first ten years were dominated by his mother’s fear of being evicted for excess noise by the landlady who lived in the apartment below them. The silent activity of reading and drawing were fuelled by the travel books that his mother brought home from the public library, opening up horizons beyond Switzerland for the young Armin Greder.

Discouraged from a career that involved drawing, Greder was apprenticed as an architectural draftsman after finishing school. He made a lot of models whilst working in an architect’s office in Switzerland. In 1970 he emigrated to Australia to take up a job in an advertising agency. Subsequently he taught drawing, design and illustration at tertiary institutions in Queensland, which gave him another creative outlet whilst pursuing his career as a children’s book illustrator.

As an internationally renowned illustrator, Greder has won many awards for his picture books, including the Children’s Book Council of Australia Picture Book of the Year 2002 for An Ordinary Day and in 2004 was nominated for the Hans Christian Anderson Award for his body of work. Greder currently resides in Lima, Peru.

Bio prepared by Margaret Bromley, University of New England, mbromle5@une.edu.au and brom_ken@bigpond.net.au

Summary

A picture book that suggests an origin for the Ursa Major constellation, the storyline of The Great Bear depicts the life of a bear in a medieval circus. Kept in a cage all day, she is an obedient dancing bear who performs every night all her life for noisy crowds, sometimes cheering, but more often tormenting her by throwing stones and poking sticks at her. We see the backs or the silhouettes of the circus performers whose cruel carnivalesque is their livelihood.

There are gaps in the simple text, but there’s an implicit suggestion that the circus owners encourage this cruelty. Is she a scapegoat for something inherently vindictive in their (possibly) unhappy community?

Armin Greder’s illustrations, presented from the bear’s point of view, invite such interpretations of the villagers’ actions depicted in the story. Their faces are not individualised and their clothing is a generic peasant costume of dull browns and yellows. Their pallid flesh, gaping mouths and wide eyes reveal their scorn towards the tormented bear as they collaborate in this incessant cruelty and bullying.

One day, as cymbals crash, trumpets blast and stones strike, the bear stands very still and quietens the crowd with a tremendous roar. No longer a submissive performer, but a ferocious bear, she is a wild animal, escaping psychological and physical captivity.

Greder’s pictures tell the rest of the story, showing the streets littered with shoes and possessions left by the fleeing townspeople.

At one end of the street a tall pole reaches to the night sky. The bear races towards it, pursued by the villagers and the circus people. She climbs the pole, higher and higher and leaps into the starry night sky of Vincent van Gogh’s painting, taking her place in celestial eternity as The Great Bear.

The first edition of The Great Bear (1999) references the tradition of using endpapers for maps as contextual information for the story within the pages. The endpapers depict a map of the night sky, showing the Zodiac symbols and images of the Northern Stellar Sky and The Southern Stellar Sky, including the Great Bear constellation, sourced from the Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and technology, Kansas City.

Analysis

The relationship of bears and humans is a recurring theme in mythology; bears are sometimes worshipped and often feared. The story of Ursa Major in Greek and Roman mythology explaining the constellations is a source of inspiration for The Great Bear. The story illustrates how astronomy is inextricably linked to ancient mythology.

The Great Bear is a direct collaboration between author Libby Gleeson and illustrator Armin Greder. The origins of the book, as explained by Gleeson, was a dream which she had, offering the sequence of events for the story. Determined to remember the images, she told Greder of the dream, who encouraged her to tell the story. Greder suggested that “It is not just a book about dancing bears, but the story of humanity and the need to set oneself free” (Gleeson, 2010, p.26) and he sent her small drawings of the bears. He also advised her to concentrate on the myth and poetry, while suggesting that the second half of the book should be wordless. Though he is adamant that the story is Gleeson’s, Greder’s pictures determine the narrative and reader interpretation.

Gleeson urged the artist to create the sky as a character. Consequently, he began work on the colourful skyscape. Greder’s illustrations echo the caricatures of Honore Daumier and the emotional use of colour and line of the German Expressionists. The visual references to van Gogh’s Starry Night Over the Rhone (1888) enable a more dreamlike transcendence of the bear’s earthly existence. As the bear moves closer to freedom, the swirls of colour intensify.

The illustrations were executed in compressed charcoal sticks, overlaid with oil pastel. Greder explains that in a picture book a character has to remain the same throughout, requiring tight control over the drawing. For him, charcoal offers this fluidity and movement and, essentially, spontaneity.

Armin Greder is an internationally renowned illustrator and is a long collaborator with Libby Gleeson. In the 1990s Australian children’s picture books were becoming established as a genre which crossed boundaries between child and adult literature. To this end, Greder’s illustrations subvert expectations of a picture book, including content for older readers. He depicts characters who could be living next door, “unashamedly offering up reflections of the darker aspects of ourselves…of conflict and fear”, which are certainly reflected in The Great Bear. Greder offers that “Hope is not an abundant commodity in my stories. They are critical, not meant to give people pleasant dreams but rather to keep them awake, perchance even to make them think” (Zoe, playingbythebook, accessed: July 23, 2018).

Libby Gleeson, however, suggests that the ending of The Great Bear is affirming and hopeful” (Rafadi, 2013 p. 53), that she wants her work “to give hope, to give reassurance, not to be unrealistic and sugary sweet, but nor to be depressing and negative” (ibid. p. 54).

For some readers the bear’s final journey to the night sky could suggest a dimension after death, an afterlife on stars and planets, depending on their interpretations of text and images.

The Great Bear is marketed as a picture book for readers aged 5 to 8. However, there is a disjunction between the simple verbal narrative and the illustration style. Though the text is accessible to a wide range of readers, the illustrations require a more sophisticated level of visual literacy. The Great Bear was re-released in 2010, as part of The Walker Classics series to include biographies and commentary by both creators, omitting the maps as endpapers. Publishers, Walker Books, have produced detailed teachers notes, aimed at years 4 and 5, (children aged from 9 to 11) which facilitate classroom study of the book. The introduction to the 2010 edition, by Robyn Ewing, Professor of Teacher Education and the Arts, at the University of Sydney, affirms the reception of this complex narrative as a classroom text for upper primary school children.

Further Reading

An Interview with Armin Greder at playingbythebook.net (accessed: July 23, 2018).

Raffidi, Mark, “Libby Gleeson” in Standing on the Shoulders of Giants: insights from Australia’s great picture book authors and illustrators, Ulladulla, New South Wales, Shore Drift, Harbour Publishing House, 2013, 51–56.

readingaustralia.com.au (accessed: July 23, 2018).

Ursa Major at en.wikipedia.org (accessed: January 9, 2018) for the mythology of Ursa Major.

van Gogh, Vincent, Starry Night Over the Rhone, created 1 September 1888.

walkerbooks.com.au (accessed: July 23, 2018).