Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

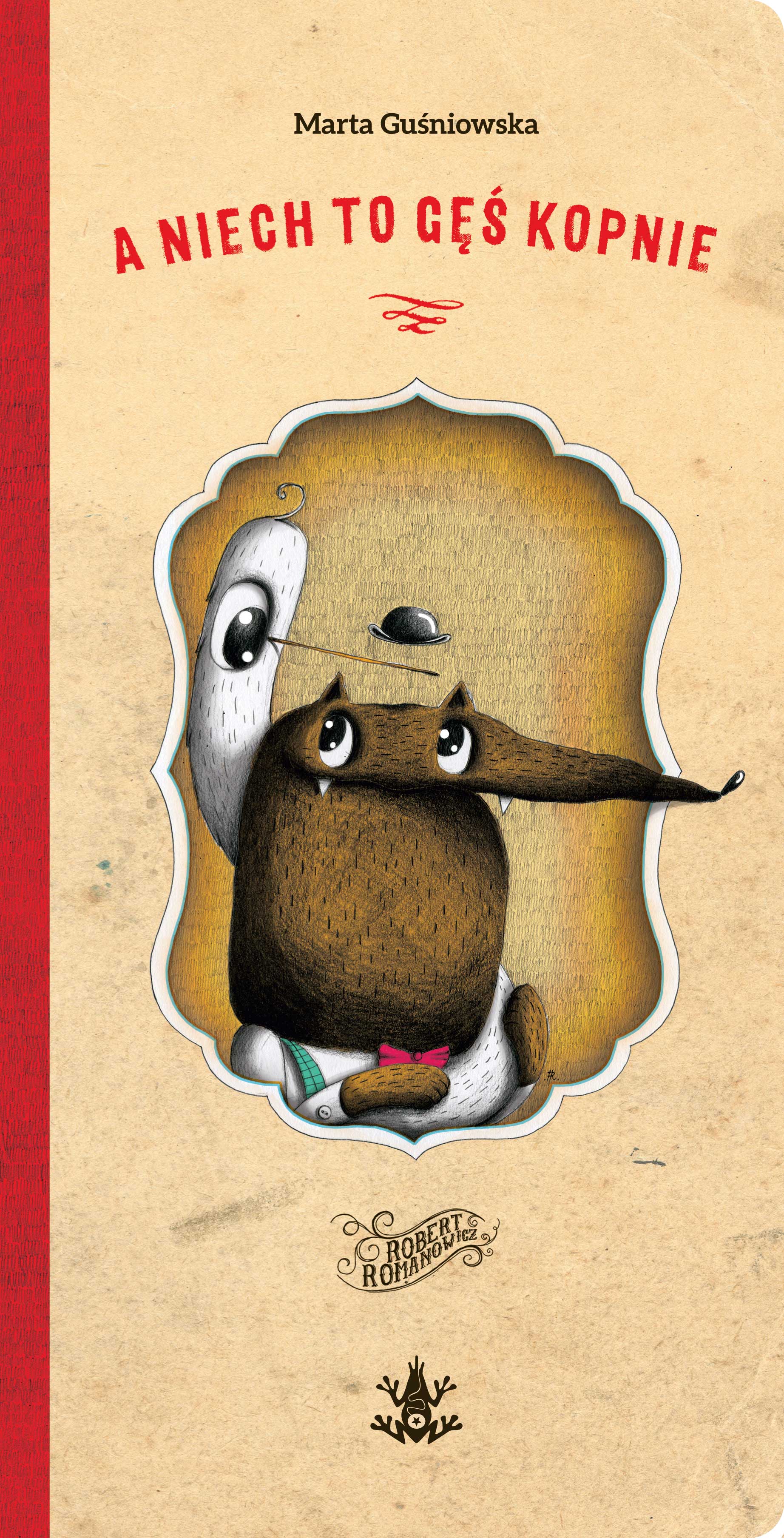

Guśniowska Marta, ill. Robert Romanowicz, A niech to gęś kopnie. Warszawa: Tashka, 2016, 96 pp.

ISBN

Awards

2017 – mention in the Book of the Year contest, organised by the Polish Section of IBBY;

2014 – Guśniowska’s play of the same title was awarded the 1st prize in the 25th Theatre Play Competition, organized by the Children’s Art Centre in Poznań;

Since its premiere in 2014, the stage adaptation of the play, directed by the author, received over a dozen awards; full list available online at teatranimacji.pl (accessed: July 6, 2018).

Genre

Fables

Fiction

Illustrated works

Target Audience

Children (According to the publisher’s website: 5+. The book’s sense of humour can possibly be enjoyed by young adults and adults too. )

Cover

Courtesy of the puublisher.

Author of the Entry:

Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Courtesy of the Author.

Marta Guśniowska

, b. 1979

(Author)

Marta Guśniowska graduated with an MA in philosophy from the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań; her thesis was on elements of Taoist philosophy in Chinese folktales. She has authored several dozen children’s plays, many of which were awarded prizes in various contests, published in the journal Nowe Sztuki dla Dzieci i Młodzieży [New Plays for Children and Young People], and adapted for the stage. She also writes lyrics for the songs used in theatrical performances. In her work, a the fairy tale tradition occupies a prominent place. Currently, she works as a dramaturg in the Białystok Puppet Theatre, while her previous employment includes co-operation with the Animation Theatre and the Children’s Art Centre in Poznań. Her most important plays are: Baśń o Rycerzu bez Konia [The Tale of the Knight without a Horse] (2004), Baśń o grającym imbryku [The Tale of the Singing Kettle] (2006), and A niech to gęś kopnie [Goosedammit] (2014).

Sources:

Legierska, Anna, Marta Guśniowska, available at culture.pl (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Drwięga, Agata, Marta Guśniowska: A Glance around the Polish TYA Part 5, available at jugendtheater.net (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Guśniowska, Marta, “Marta Guśniowska o sobie,” Gabit 23 (2006): 2, available at pleciuga.pl (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Bio prepared by Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Questionnaire

1. What drew you to writing about Classical Antiquity?

In the beginning, I wasn’t planning to write a piece with such a reference. Initially, I mostly created the main characters, then – the minor ones and the events. In the course of this process, new ideas were coming up. When it comes to Mr. Otter, an allusion to Charon seemed to me to be both an obvious and funny one, and that’s why it appeared in the book.

2. Why did you choose Charon to be referred to in your work?

I chose to reference him because it “matched” the scene. From the one hand, I was looking for a figure of a carrier – and I found one. From the other hand, Charon is one of the mythological characters that impressed me the most when I was reading myths as a child. His secrecy and strangeness, the darkness surrounding him and the fact that he was believed to cross the borders between the two worlds – all of this was fascinating. In my book, the Old Carrier initially seems to be a mysterious and sinister person – but soon he reveals his “human” face. In this way, a kind of a “disenchantment” of the figure takes place – and this issue has always been interesting to me, especially in the context of the taboo of death.

3. Was this allusion intended to be understood by the adult readers? Or by the children too?

I usually write my works having both of them in my mind. I think that good children’s literature should work on many levels and appeal to the other members of the young reader’s family too. In a particular tale, different persons can find different things – according to their age, the stage of their development, their knowledge of literature and ability to notice references to other works. Charon is generally a wink to adults, but children also read myths, as well as fairy tales.

4. In the book, Mr. Otter uses the words alluding to Dante’s Divine Comedy. Were you thinking only about this work when creating the character? Were there any other sources used in this process?

I had the Divine Comedy in my mind – the character and the scene we are talking about were supposed to be a humorous reference to Dante’s work. However, I didn’t want to delve deeper into this issue in order to make things more elaborate. I think that the wisdom and various references should be somehow veiled in a fable rather than smacked in the reader’s face. If someone notices a reference – that’s great, if not – that’s not a problem. This way, we can avoid didacticism, which I don’t like very much.

5. Speaking about didacticism, I would like to ask you a different question. In your book, there are many elements which are typical for the Aesopian tradition of fable. Did you have Aesop’s fables in mind when creating your own story?

Not exactly; I was not thinking about these fables specifically. However, I was raised on such stories, so they somehow run in my blood – and what is “hidden” in us sometimes wants to go to the surface. The Aesopian formula of fable seems to me to be very natural – writing about humans “disguised” as animals is pleasant and safe at the same time. People know that the story is about them, but they don’t feel offended. What is more, animal characters stun the imagination – and the act of de-stereotyping their images is great fun, so I do it quite often by creating a Fox who is drippy, and an Owl who isn’t smart at all, and many others.

6. Do you think that classical and ancient myths, history, and literature continue to resonate with young audiences? If yes, why?

Yes, of course. Myths, similarly to fairy tales, will never get old. As they are timeless and carry universal values and wisdom, they will always appeal to the readers, no matter their age and the time period. Moreover, I think that referencing them in contemporary literature is a great idea. Maybe some of the recipients of my book would like to know more about its classical roots and read myths?

7. And what about you? Are there any books that made an impact on you in the field of myths?

When I was a child, I loved reading Jan Parandowski’s Mythology so, as I stated before, the association of Mr. Otter with Charon was totally an obvious one.

8. You are a critically acclaimed author of children’s and young adults’ plays, as well as a director and a dramaturg. Do you plan to utilize classical motifs in your next written works and theatrical performances?

Yes, for sure! I don’t think about anything particular now, but the antiquity is very close to me. My sister is an archeologist by education, while I graduated in philosophy. I’m keen on ancient philosophy in particular – in my opinion, the antiquity was the most interesting period I studied, because it’s the most fabulous, remarkable, and beautiful.

Prepared by Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Courtesy of Robert Romanowicz.

Robert Romanowicz

, b. 1976

(Illustrator)

An architect, illustrator, writer, theatre set designer. He graduated from the Faculty of Architecture at Wrocław University of Science and Technology and from The School of Advertising “Creo,” also in Wrocław. He created illustrations for many children’s books, such as Malina Prześluga’s popular series about Ziuzia (2013–2016), Julia Cholewińska’s Skarpety i papiloty [Socks and Curlers] (2013), or Marta Guśniowska’s A niech to gęś kopnie [Goosedammit] (2016). Additionally, he authors his own books: Mali opowiadacze [Little Storytellers] (2014), Rymowane cyferki [Little Rhymed Figures] (2014), a series of early-concept multilingual picture books about, respectively: vehicles, animals, objects, and food, as well as another series – children’s guides to Polish cities: Kazimierz Dolny, Kraków, Wrocław, Warszawa, and Zakopane. He also creates illustrations for magazines as well as covers, posters, installations, tunnel books, pop-up books, tattoos and photographs, and runs workshops for children. His works were presented in many galleries and at various exhibitions, both in Poland and abroad.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: June 25, 2018).

About, available online (accessed: April 28, 2018).

Robert Romanowicz, available online (accessed: April 28, 2018).

Bio prepared by Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Adaptations

Guśniowska’s play of the same title was adapted for the stage. The first performance, directed by the author herself, premiered in 2014 in the Animation Theatre in Poznań. Guest performances of this staging of the play were later shown in various Polish cities, as well as abroad (Moscow, Montreal). Another theatrical version of A niech to gęś kopnie, directed by Robert Drobniuch, premiered in 2016 in the Puppet and Actor Theatre ‘Kubuś’ in Kielce.

Summary

The book tells a story of a Goose who lives on a farm. The protagonist is extremely slim, has a sunken stomach, and her feathers are frayed. This is because the bird suffers from depression – apart from a visible loss of appetite, she has a low self-esteem, cannot sleep, and continuously sighs in sorrow. Therefore, when a Fox enters the farm, she suggests the intruder eat her instead of a Hen. The predator, despite being unable to capture a hen, refuses to comply with the Goose’s request. The characters begin a journey, which is supposed to lead them to another carnivorous animal – the Wolf. However, the peregrination soon becomes a quest to find the meaning in the Goose’s life. On the way, the bird and the Fox meet, respectively, the Bear, Mrs. Hare with her many children and, interestingly, the Old Carrier – a character clearly based on Charon who, according to Greek mythology, was Hades’ ferryman. As it turns out, the seemingly scary creature is in fact a much more kind and gentle Mr. Otter. Unfortunately, the Goose constantly repeats that the advice given by all the animals she meets does not make her any closer to finding the meaning in her life. Eventually, the couple reach the Wolf’s house, where the host agrees to eat the bird. When the Goose is boiling in the water, she starts to understand that her life is not meaningless – especially when the Fox says that he is going to miss her, it makes the bird truly happy for the first time. As she loses consciousness, her companion, along with the Wolf, the Bear and Mr. Otter, unsuccessfully try to turn off the stove. The Goose wakes up, sees that she has friends who do not want her to die, and – and having found meaning in her life – blows out the flame under the burner. The story ends up with the Fox and the Goose – not depressed anymore – living “happily ever after.”

Analysis

The story may be seen as a contemporary variation on the Aesop’s fable tradition. On the one hand, it uses some of the genre characteristics, such as anthropomorphic animals, a satirical tone, and a moral highlighted at the end. On the other hand, the book inverts the Aesopian fable paradigm, as it does not provide a closure, in which the "stronger" and "cleverer" animal would triumph over the "weaker" and “sillier” one – in fact, the book departs from contrastive stereotyping of its characters.

The most direct link to classical antiquity is provided by the Goose and the Fox meeting Mr. Otter – a Charon-like ferryman. They encounter him shortly after they reach the river. Covered in fog, the stream evokes an ambience of horror and resembles Acheron and Styx, the rivers of Hades. Mr. Otter himself, with his grim voice and a hood covering his face, initially seems to be a terrifying creature. It should be mentioned that the Old Carrier, as he introduces himself, is an allusion not only to Greek mythology, but also to Dante. Mr. Otter paraphrases the sentence written on the Gates of Hell in the Divine Comedy: “All wood abandon ye who sail here!”* It is particularly important that the Goose and the Fox meet an equivalent of Charon just before they reach the Wolf’s house, for the encounter with this unusual “soul carrier” precedes the end of their journey, when they will have to face their fate in the symbolic underworld. However, after taking the hood off and changing his voice, Mr. Otter turns out to be a lovable person and a great companion for the Goose and the Fox. He helps them reach the other bank of the river and gives the bird a little hope instead of suggesting she should abandon it, therefore subverting the popular image of Charon. The end of the story, by making the symbolically reborn Goose live happily, highlights the significance of the departure from both the classical and Dante’s portrayals of Charon, and also echoes Odysseus’ journey to the underworld

* Marta Guśniowska, A niech to gęś kopnie, ill. Robert Romanowicz, Warszawa: Tashka, 2016, p. 69; translation by Maciej Skowera based on H. F. Cary’s English translation of the Divine Comedy (Hell, III, 9), available online at gutenberg.org (accessed: August 9, 2018).

Further Reading

Butler, Rebecca, “The Monsters of Depression in Children’s Literature: Of Dementors, Spectres, and Pictures”, Journal of Children’s Literature Studies 2.1 (2005): 27–39.

Drwięga, Agata, “Dramaty (nie)zwierzęce w teatrze lalek dla dzieci” [(Non)Animal Plays in Puppet Theatre for Children], Polonistyka. Innowacje 5 (2017): 103–119, available online at pressto.amu.edu.pl (accessed: August 9, 2018).

Addenda

The book is based on Guśniowska’s play of the same title, published in 2014 in the journal Nowe Sztuki dla Dzieci i Młodzieży.

The illustration (pp. 70–71) showing Mr. Otter who helps the Goose and the Fox to reach the other bank of the river, courtesy of Tashka, the publisher.