Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Jennifer Cook, Ariadne: The Maiden and the Minotaur. South Melbourne: Lothian Books, 2004, 206 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Alternative histories (Fiction)

Fiction

Mythological fiction

Novels

Target Audience

Young adults

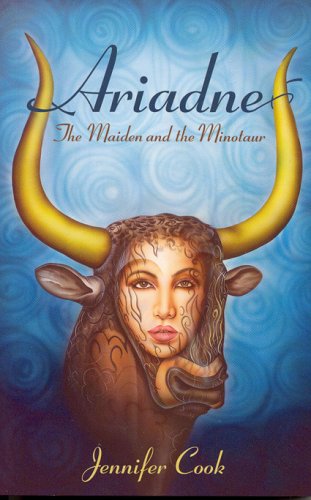

Cover

Cover used with permission from Ariadne: The Maiden and the Minotaur by Jennifer Cook, Hachette Australia, 2004.

Author of the Entry:

Miriam Riverlea, University of New England, miriam.riverlea@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaounde 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

Jennifer Cook

, b. 1968

(Author)

Jennifer Cook is the author of two young adult novels focusing on classical myth: Ariadne: The Maiden and the Minotaur (2004) and Persephone: Secrets of a Teenage Goddess (2005). Educated in Donvale, a suburb of Melbourne, she went on to study classics at the University of Melbourne. After a period of teaching at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, Cook began work as a journalist, first with a local newspaper and then with SBS and ABC television networks. In 2007 she published a picture book, The Screaming Irrits, illustrated by Shane Nagle. She has worked as a print and radio journalist, and has received the United Nations Media Peace Award for a radio feature on East Timor. At the time of writing, she is close to completing her PhD in journalism.

Bio prepared by Miriam Riverlea, University of New England, mriverlea@gmail.com

Translation

Braille: Ariadne: The Maiden and the Minotaur, Vision Australia Information Library Service, Sydney, 2008.

Summary

Cook’s story opens with sixteen-year-old Ariadne abandoned on Naxos, furious that she fell for Theseus, who has taken up with her sister Phaedra and sailed home to Athens. As in the traditional version of the myth, Ariadne falls in love with Theseus when he arrives on Crete as one of the Athenian tributes, destined for death in the labyrinth. But in this story, the Minotaur is not a monstrous beast, but instead a small child afflicted with a club foot, a hare-lip, and other deformities. Child of Ariadne’s mother Pasiphae and Pistrades, a Priest of Dionysus, the boy Taurus grows up imprisoned in the labyrinth on the orders of jealous Minos, who deliberately disseminates the story about Pasiphae copulating with the bull to bolster his own power. But Taurus is protected by a loyal retinue of attendants, including both his parents, the Dionysian acolyte Pleides, and the female members of the royal house. With Daedalus’ help, the labyrinth is built not only as a dangerous place to keep out intruders, but also a palace of wonders for the little boy to play in.

Ariadne falls for the handsome hero Theseus as soon as he disembarks from his ship, unaware that his flirtatious glances in her direction are in fact directed at her sister Phaedra. When Theseus announces that he will enter the maze and slay the monster, Ariadne devises a plan to save her beloved little brother. She reveals to Theseus the true nature of Taurus and presents him with a thread soaked in her own magic spells to guide him through the maze. She plans to procure for him the head of a slaughtered bull to present to Minos as evidence of his supposed victory, and Theseus agrees to keep Taurus safe from harm. But after entering the maze and killing the guards, including Pistrades, Theseus loses Ariadne’s thread and is confronted by the demons of his own past. In a confused attempt to protect his child-self, he ends up slaying Taurus. Pasiphae and Phaedra help to conceal this awful truth from Ariadne as the two sisters, now betrothed to Theseus and his friend Perithous, set sail for Athens, accompanied by Ariadne’s friend (and eventual love interest) Pleides.

After Ariadne catches Theseus and Phaedra kissing, she confronts the hero and discovers what really happened in the labyrinth, although Theseus himself remains uncertain of what occurred in that strange place. As the ships sail on to Athens, Ariadne and her now-boyfriend Pleides settle on Naxos, living a peaceful life among the fishermen and establishing a new temple to the god Dionysus. Ariadne says that she is relieved to have escaped her family and reputation, though she admits that she is secretly glad that “the myth of Ariadne would survive long after my bones have turned to dust” (pp. 204–205).

Analysis

Ariadne: The Maiden and the Minotaur reconstructs the Minoan mythic cycle in terms that are relevant to a teenager of the twenty-first century. Ariadne’s first-person narrative is colloquial, candid, and full of swear words. Her relationships with her mother, father, and siblings are rendered in contemporary terms. Her parents embarrass and infuriate her, and she hates it when her sister Phaedra borrows (and then ruins) her clothes without permission. Her attraction to Theseus has all the hallmarks of a teen romance.

Alongside these preoccupations, the text comprehensively details the background of the Cretan mythic cycle, explaining the origins of the hostility between Crete and Athens, Theseus’ heroic exploits, and Pasiphae’s ancestral connections. The story’s conclusion sets the scene for the events which follow, including Aegeus’ suicide and the marriage of Theseus and Phaedra. It is clear that Cook has studied classical mythology extensively and chosen mythic variants that suit her refashioning of the narrative. The Bibliography features a range of ancient texts as well as key critical resources on myth. It also includes Thucydides’ The History of the Peloponnesian War, which forms the basis of a vivid description of the plague that Minos arranges to afflict his Athenian enemies.

The status of women in ancient society is an important theme of the work. As a princess of marriageable age, Ariadne resents the limits placed upon her body and behaviour. She relishes the freedom of spending time in the labyrinth, finding the palace more of a prison than the underground maze. But while Pasiphae unhappily reflects “what power does a woman have in our world?” (p. 153), the text reveals that female power structures underpin the Minoan royal family. Although built by Daedalus on Minos’ orders, the labyrinth is “soaked in” the magic of Pasiphae, (157), and presided over by the dark goddess Hekate. Ariadne learns that it is her mother, not her father, who manages the sacrifice of the Athenian tributes, and is appalled by Minos’ manipulation of the myth as a means of bolstering his regime. The bonds between sisters, and mother and daughter, are depicted as fraught but ultimately powerful relationships. Cook also emphasises the strength of the female line through Ariadne’s extended family, highlighting her relationships with Hekate, Circe, and Medea. Hekate tells Ariadne: “Your strength lies in those women who have gone before you but your spirit is your own” (p. 61).

As part of Cook’s feminist and revisionist approach to the myth, the text explores the flexibility of the mythological tradition to be refashioned anew. Ariadne asserts her right to tell her own story, declaring: “This is my cloth and I’ll weave it how I will” (p. 41). Like her protagonist, Cook designs a new version of the Cretan myth. Theseus is fleshed out as a complex, flawed character, haunted by memories of childhood abuse and the countless people he has killed. The refashioning of the Minotaur as an innocent child challenges the traditional practice of the othering of the monstrous in myth. And in the end, Ariadne finds happiness by bowing out of the world of myth. In depicting her simple life with Pleides, Cook invents a rational alternative for the myth of her rescue by the god Dionysus himself.

Further Reading

Hale, Elizabeth, “Friday essay: Feminist Medusas and outback Minotaurs – why myth is big in children’s books”, in The Conversation, June 3, 2016, available at theconversation.com (accessed: August 12, 2018);

Whitney, Nadine, “Ariadne: The Maiden and the Minotaur” (Book Review), in Australian Bookseller & Publisher, 83.9, Apr 2004: 46, available at search.informit.com.au.ezproxy.lib.monash.edu.au (accessed: August 2, 2018).