Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

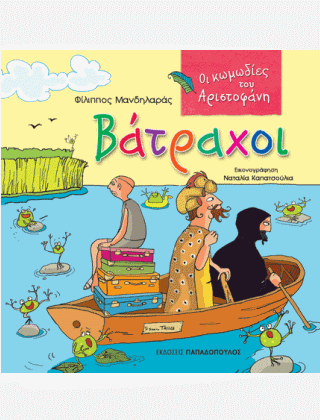

Filippos Mandilaras, Βάτραχοι [Vátrachoi], Aristophanes Comedies [Οι Κωμωδίες Του Αριστοφάνη (Oi kōmōdíes tou Aristofáni)]. Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2011, 36 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Illustrated works

Target Audience

Children (3+)

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher. Retrieved from epbooks.gr (accessed: July 5, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Natalia Kapatsoulia (Illustrator)

Natalia Kapatsoulia studied French Literature in Athens, and she worked as a language tutor before embarking on a career as a full-time illustrator of children’s books. Kapatsoulia has authored one picture book Η Μαμά πετάει [Mom Wants to Fly], which has been translated into Spanish Mamá quiere volar. Kapatsoulia, who now lives on the island of Kefalonia, Greece, has collaborated with Filippos Mandilaras on multiple book projects.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Profile at the epbooks.gr (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Filippos Mandilaras

, b. 1965

(Author)

Filippos Mandilaras is a prolific and well-known writer of children’s illustrated books and of young adults’ novels. Mandilaras studied French Literature in Sorbonne, Paris. His latest novel, which was published in May 2016, is entitled Υπέροχος Κόσμος [Wonderful World], and it recounts the story of teenage life in a deprived Athenian district. With his illustrated books, Mandilaras aims to encourage parents and teachers to improvise by adding words when reading stories to children. Mandilaras is interested in the anthropology of extraordinary creatures and his forthcoming work is about Modern Greek Mythologies.

Sources:

In Greek:

Profile on EP Books' website (accessed: June 27, 2018).

i-read.i-teen.gr (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Public Blog, published 15 September 2015 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Press Publica, published 28 January 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Linkedin.com, published published 6 May 2016 (accessed: February 6, 2019).

In English:

Amazon.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

On Mandoulides' website, published 7 March 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

In German:

literaturfestival.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Summary

The book opens with a presentation of the main characters in the plot. The Greeks, we read, believed that dead people descended to the underworld, to Hades. Dionysos, however, wanted to bring a great poet back to the world of the living. Hence, Dionysos, disguised as Herakles, made his way to Hades together with his servant, Xanthias. The real Herakles helped Dionysos with directions. When they reached a bottomless lake, Charos, who had a boat, refused to take Xanthias’ donkey on board. The donkey had to stay behind. Many frogs sang loudly and happily, as Dionysos, Xanthias, and Charos crossed the lake.

We read that when Dionysos and Xanthias reached the palace of Pluto in Hades, Aiakos was unwelcoming because Herakles had stolen the dog of the underworld, Cerberus. To enter the palace, Dionysos had to dress Xanthias up as Herakles.

As we then discover, Xanthias and Aiakos overheard the playwrights Euripides and Aeschylus arguing about who is the better. In the pages that follow, the readers witness the contest between Euripides and Aeschylus. The competition was fierce. Dionysos came up with the idea to weigh the verses of the two tragedians. Aeschylus won, and set off on his journey back to Athens. The story closes with the frogs continuing with their singing in the lake.

The final page, which presumably targets adult readers, offers background information about Aristophanes, The Frogs, Aeschylus, and Euripides.

Analysis

It is usually a difficult challenge to translate and adapt Aristophanes’ witty humour, especially for young children.* Mandilaras’ adaptation of Aristophanes’ The Frogs takes the form of vivid dialogues between protagonists, who are often direct and insulting to each other. The language is colloquial and draws from modern youth culture. The colloquialisms make the story accessible. Cerberus is described as ‘our good doggy’ [my translation], and no reference is made to its fierce nature in ancient texts (e.g., Iliad 5.646; Hes. Theog. 311 f., 767–73). Because of the characters’ lively exchange of words, readers may forget that the actors are mythical personas and personifications (e.g., Charos is the Greek word for death). Any reference to mythology seems to be suppressed. Hades is a landscape, and not a mythical figure, the son of Cronus and Rhea and Persephone’s husband.

The purpose of the information at the end of the book appears to be to contextualise comedy and tragedy within the literary output of Classical Athens, educating readers further about who is who when it comes to historical persons (Aristophanes, Aeschylus, and Euripides). No background information is offered for Dionysos, the main character in the plot here. Another book by the same author and illustrator, nonetheless, covers how Dionysos may have inspired the origins of theatrical performances: ‘Dionysos, the merry god’.**

The plot unfolds more as a sequence of events, and less as a theatrical performance. Indeed, in the first page, the narrative is characterised as a ‘story’. It is only the illustration at the bottom of the page that alludes to ancient theatre. The image shows two males and two females dancing, flanked by two large lekythoi (oil jars). The lekythoi seem to function as stage props, and we see lekythoi again outside the palace of Pluto.

Such ceramic shapes, with their distinct cylindrical bodies and long narrow necks to control the flow of oil, were customarily offered as grave gifts in Classical Athens. The depiction of lekythoi is suited for a story that is happening in the underworld. Kapatsoulia’s drawings of lekythoi imitate a well-known white lekythos by the Achilles Painter (ca. 440 BCE), kept in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. The scene on the lekythos shows a young male warrior saying goodbye to his wife, who, appropriately for the lady of the house, sits in an elaborate chair.*** This lekythos is an iconic image of Classical art, not least because the warrior’s figure points to naturalistic statuary. Children may encounter depictions of this lekythos again and again in their school textbooks and other educational materials.

Additional drawings of material culture are more modern-looking, such as Xanthias’ suitcases, the grid sheet on which Herakles draws his directions, and the golden school bell kept by a female time-keeper during the two playwrights’ contest. What makes the narrative especially accessible to young children, however, is the likeness of the contest to modern TV-shows, to ‘Greece’s Got Talent’ [my translation], as we read in a large chiseled inscription on the judge’s stone bench. Readers may forget that the contest takes place in an imaginary location in ancient times, and think instead that Euripides and Aeschylus perform before a TV audience.

Learning the story of Aristophanes The Frogs may assist children with their studies in elementary and high school. The motif of travelling to Hades is recurrent in Modern Greek literature, including folk songs [demotika tragoudia in Greek] and poetry from the more recent past. The Greek poet, Kostis Palamas (1859—1943), for example, has written a collection of poems that is entitled The Grave [O Taphos in Greek] (1898). **** The lyrics, which start with Charos’ journey to Hades [kavala paei o Charontas…], have been popularised in modern songs that are known widely in Greece.*****

* See, for example, James Robson, 2008. ‘Lost in Translation? The Problem of (Aristophanic) Humour’, in Lorna Hardwick and Christopher Stray, eds., A Companion to Classical Receptions: 168–182. Blackwell Publishing.

** See Διόνυσος, ο κεφάτος θεός (accessed January 26, 2019)

*** Athens, National Archaeological Museum, Inventory number: 1818; Vase Number in the online database of the Beazley Archive: 213983. See, for example: greece-athens.com (accessed January 26, 2019)

**** See (accessed January 26, 2019)

***** See for example: kithara.to/stixoi, (accessed January 26, 2019)

Further Reading

Information about the book:

Epbooks.gr (accessed Ferbruary 11, 2019)

Addenda

Published in Greek, 1 November 2011. Hardbound.