Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

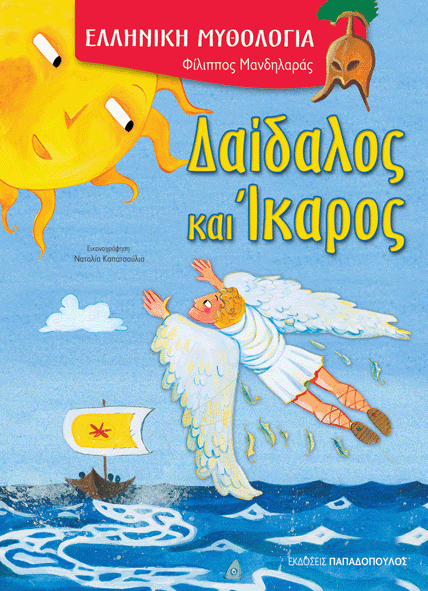

Filippos Mandilaras, Δαίδαλος και Ίκαρος [Daídalos kai Íkaros], Greek Mythology [Ελληνική Μυθολογία (Ellīnikī́ Mythología)]. Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2012, 16 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Illustrated works

Target Audience

Children (Children aged 4+)

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher. Retrieved from epbooks.gr (accessed: July 5, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Natalia Kapatsoulia (Illustrator)

Natalia Kapatsoulia studied French Literature in Athens, and she worked as a language tutor before embarking on a career as a full-time illustrator of children’s books. Kapatsoulia has authored one picture book Η Μαμά πετάει [Mom Wants to Fly], which has been translated into Spanish Mamá quiere volar. Kapatsoulia, who now lives on the island of Kefalonia, Greece, has collaborated with Filippos Mandilaras on multiple book projects.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Profile at the epbooks.gr (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Filippos Mandilaras

, b. 1965

(Author)

Filippos Mandilaras is a prolific and well-known writer of children’s illustrated books and of young adults’ novels. Mandilaras studied French Literature in Sorbonne, Paris. His latest novel, which was published in May 2016, is entitled Υπέροχος Κόσμος [Wonderful World], and it recounts the story of teenage life in a deprived Athenian district. With his illustrated books, Mandilaras aims to encourage parents and teachers to improvise by adding words when reading stories to children. Mandilaras is interested in the anthropology of extraordinary creatures and his forthcoming work is about Modern Greek Mythologies.

Sources:

In Greek:

Profile on EP Books' website (accessed: June 27, 2018).

i-read.i-teen.gr (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Public Blog, published 15 September 2015 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Press Publica, published 28 January 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Linkedin.com, published published 6 May 2016 (accessed: February 6, 2019).

In English:

Amazon.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

On Mandoulides' website, published 7 March 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

In German:

literaturfestival.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Adaptations

The book is an adaptation of the book published in 2009 within the series My First Mythology:

Filippos Mandilaras, Δαίδαλος και Ίκαρος [Daidalos kai Ikaros], Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2009, 36 pp.

Demo of 9 pages available at epbooks.gr (accessed: October 13, 2021).

Summary

Daedalus was a celebrated sculptor who produced life-looking statues in Athens. People admired Daedalus’ work, but praised also Daedalus’ nephew, Talos. When Talos was found dead, the Athenians thought that Daedalus might have been envious and killed Talos. Daedalus left for Crete. King Minos asked Daedalus to build a prison to confine the Minotaur, a monster with a human body but a bull’s head and tail.

For many years Daedalus lived in King Minos’ palace. He had a beautiful blue-eyed son, Icarus. One day, however, Minos got angry with Daedalus because Daedalus gave the key of the labyrinth to Ariadne and, as a result, Theseus killed the Minotaur. Theseus and Ariadne ran away. Minos had Daedalus and Icarus arrested and imprisoned. Whist in custody, Daedalus continued to be industrious, and he designed machines. Young Icarus could not stand the prison. Daedalus came up with a plan. He made wings to fly with by joining together birds’ feathers with wax. Daedalus and Icarus escaped on a pitch-dark moonless night. When morning came, Daedalus advised his son to fly neither close to the sun nor close to the sea. Icarus loved the flying so much that he forgot his father’s advice. As he flew high, the sun melted the wax and Icarus plummeted to his death. His body fell near an island where the wind still blows fiercely. If readers happen to visit the island today, they will understand Icarus’ joy as he flew.

Analysis

The book offers a concise account of who Daedalus and Icarus were, and how Icarus met his death. The well-known story is adapted for children as young as four, and no explicit reference is made to hybris and punishment. A subtle moral message, nonetheless, may emerge as follows. Icarus died because he disobeyed his father.

Throughout the book there is an emphasis on a strong father-son relationship, and the benefits but also risks arising from this bond. Daedalus wants his son to be happy. He is inventive and finds a way to take his son and himself out of prison. Icarus loves his father. As he falls to his death, Icarus shouts “Help me, Dad” (my translation, «Βοήθεια, πατέρα!» in Greek), alas it is too late. Icarus dies because he behaves irresponsibly and fails to trust his father.

Acting like a child, Icarus is far too joyful that he can fly. We read that he made acrobatics in the air. He touched the waves, and then he flew high to kiss the sun. In a sense, Icarus did not confront reality but lived in a fantasy world defying the laws of nature. Daedalus could no longer intervene and save his son, because at a high temperature wax changes state from solid to liquid. There appear to be limits as to what humans, even in the realm of myth, can achieve. After all, Daedalus was a craftsperson who worked with materials (e.g., marble, feathers, wax, ropes), and he was not endowed with super-human powers.

Flying is portrayed as a wonderful experience. On the one hand, flying could fascinate young children. On the other, as Icarus does not survive the flight, children may become scared. Icarus, with his blond curly hair and white tunic resembles flying Hermes, as shown in another book by the same author and illustrator Hermes. The god for all chores (my translation).* Hermes has small wings at his feet. By contrast, Icarus’ large wings spring from his shoulder, and quite possibly enable him to perform his acrobatics. There is a cartoon-like dialogue between Daedalus and Icarus as they fly away from prison at night. Daedalus says: “At last, humans have acquired wings” (my translation, «Να που ο άνθρωπος απέκτησε φτερά» in Greek). Icarus replies: “it is wonderful to see the earth from above” (my translation, «Υπέροχο να βλέπεις τη γη από ψηλά» in Greek). Young children may think of popular characters in the cartoon, television, and film industries, such as Superman, who can fly (though without wings). In addition, children may think of aeroplanes, and pilots’ thrill of getting a bird’s eye view. Within the context of Modern Greece, in particular, becoming a fighter-jet pilot is one of the most highly-esteemed professions. Many young children aspire to become such pilots. The Hellenic Airforce Academy is named after Icarus, “Σχολή Ικάρων.”** Clearly, in appropriating Icarus’ name, the emphasis is on flying, and not on Icarus’ demise.

In the opening page, we read that Daedalus fashioned sculptures that looked alive. Accordingly, the illustration shows human-like marble statues. Quite realistically, a woman in stone stretches her left arm to tease Daedalus. With her finger tips she touches Daedalus’ nose. Red hearts, as in cartoons, emanate from this touch. The hearts seem to convey that the statue is pleased with Daedalus’ craftsmanship, and that the sculptor is also happy with his creation. In art-historical parlance, the term ‘daedalic’ is used to describe early sculptures of the Archaic period,*** such as the ‘Kore of Nikandre’ from ca. 650 BCE. **** Nikandre’s body is relatively flat with straight arms resting at her side. Her head has a triangular shape, which is also accentuated by a triangular wig. Such sculptures were rigid and rather mathematical renderings of the human form. They lacked the naturalism of Classical bodies that Athenian sculptors made from ca. 480 BCE onwards. By crediting Daedalus with naturalistic images, however, Mandilaras and Kapatsoulia may have in mind a fragment of the playwright Aeschylus (Aeschylus fr. 78a.1-12 Radt).***** The fragment is from a lost satyr-play, Theoroi or Isthmiastae (Spectators/Ambassadors at the Isthmian Games). Satyrs marvel at fine look-alike images (portraits) of themselves that were made by Daedalus. The fragment could echo the increasing realism in contemporary late Archaic and early Classical art.******

Daedalus, nonetheless, remains a figure from pre-Classical times, as implied by his connection with Bronze Age Crete. In fact, the Linear B tablets mention a place name, perhaps of a building or shrine, ‘da-da-re-jo-de’.******* Whether the root of this name refers to Daedalus is contested in scholarship.******** In any case, learning about the labyrinth and the Minotaur will inspire young children to read more books about Greek mythology, including Theseus in the same series.*********

Based on this book, Icarus seems to have been more influential than his father. We do not read that Daedalus survived and reached Sicily. According to Herodotus (7.170.1) Minos pursued Daedalus in Sicily, but Minos died there. Rather, the book closes with the island named after Icarus’ fall in the sea. For readers familiar with Greece’s geography, the meaning of the name ‘Ikaria’, an island in the eastern Aegean, is easy to guess. The illustration on the last page shows a female backpacker and a sign ‘rooms to let’ in Greek characters. Tourism, the modern reality of the Greek islands, need not necessarily distract readers from thinking about mythology, especially about a character who “could really fly” (my translation, «πετούσε αληθινά» in Greek).

* epbooks.gr (accessed: March 1, 2019).

** See haf.gr (accessed: March 1, 2019) and haf.gr/en/(accessed: March 1, 2019).

*** britannica.com (accessed: March 1, 2019).

**** Athens, National Museum, inv. 1. See (accessed: March 1, 2019).

***** See (accessed: March 1, 2019).

****** See, for example, Stieber, Mary, "Aeschylus' Theoroi and Realism in Greek Art", Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-) 124 (1994): 85–119. doi:10.2307/284287 (accessed: March 1, 2019),

******* See Bennet, John, "The Structure of the Linear B Administration at Knossos", American Journal of Archaeology 89.2 (1985): 231–249. doi:10.2307/504327 (accessed: March 1, 2019).

******** See Hurwit, Jeffrey M., The Art Bulletin 76.2 (1994): 358–364. doi:10.2307/3046027 (accessed: March 1, 2019).

********* omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl (accessed: March 1, 2019).

Addenda

Information about the book. Soft bound.