Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Ursula Dubosarsky, The Golden Day. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2011, 160 pp.

ISBN

Awards

2012 – Luchs (Lynx ) Award for Children's Literature for The Golden Day (in German Nicht Jetz, niemals);

2014 – International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY) Honour Book List.

Genre

Detective and mystery fiction

Fiction

Magic realist fiction

Novels

Teen fiction*

Target Audience

Young adults

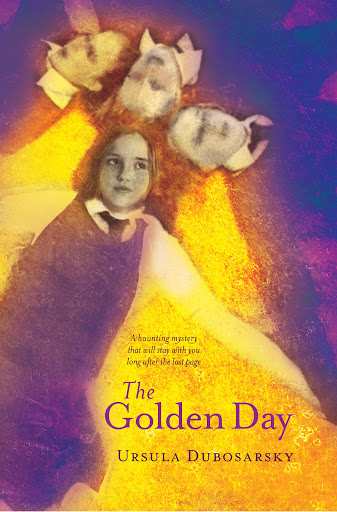

Cover

Courtesy of the publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Miriam Riverlea, University of New England, mriverlea@gmail.com

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaoundé 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

Courtesy of the Author.

Ursula Dubosarsky

, b. 1961

(Author)

Ursula Dubosarsky is an Australian writer of children’s and young adult fiction. Born in Sydney in 1961, she received an education in classical languages and literature at the University of Sydney (1982). She has a PhD in English Literature from Macquarie University (2008). She travelled to Israel and worked on a kibbutz, where she met her Argentinian husband. Her work is influenced by her travel, by an enjoyment of word play, intertextual referents, and an empathy with her child characters. Her child characters tend to be intelligent, intense, and observant loners. She is also very fond of guinea-pigs, which appear in many of her works.

Source:

Official website (accessed: September 4, 2020).

Bio prepared by Margaret Bromley, University of New England, brom_ken@bigpond.net.au and Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Questionnaire

1. What drew you to writing/working with Classical Antiquity and what challenges did you face in selecting, representing, or adapting particular myths or stories?

Well, things you read stick in your mind as a writer and I suppose you store them away for the future, without conscious intentions. I loved the tone and energy of Ovid’s Metamorphoses from my very first reading when I was 12 in a Year 8 Latin class, translating the Pyramus and Thisbe episode and then the story of Io. I found them enchanting, unsettling and very funny. They were not stories I had ever read before.

At much the same time as I was reading the Metamorphoses I also saw a school French production of Jean Anouilh's Antigone which made an enormous impression as a work of art; then a couple of years later I saw another school production of Offenbach's Orpheus in the Underworld. A very different approach to Anouilh! and yet the works have much in common, in their apprehension of the classical world, not something alien and distant from modern society, but endlessly resonant. Then we read A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and another extremely entertaining incarnation of Pyramus and Thisbe. I’m sure all these works, all written for stage, were fundamental to my choice of Ovid when I was asked, 35 years later, to write some plays for primary school children for the NSW School Magazine.

I was under a certain constraint with the plays, particularly in regard to the sexual activity which is central to several of the stories, as the School Magazine is an official publication of the NSW Department of Education. There was some concern from higher up in the Department (not the Magazine itself) from the very first play, "Io, the Girl who turned into a Cow" – it was felt to be crossing the line of decent behaviour and a bad model for children. There was a meeting called, and a discussion held, but in the event the play was published without alteration, and no objections were raised to further plays.

In the novels, Theodora’s Gift, How to Be a Great Detective, Black Sails White Sails, The Golden Day and The Blue Cat, for the most part the classical myths are adapted almost secretly – the reader often may have little idea that I am working from a classical story, which they may or may not be familiar with. It is almost something that feeds me as a writer, than helps me find mirrors of meaning, watery shadows deep under water of centuries of human storytelling. The same is true of the use of Biblical stories in The First Book of Samuel and again Theodora’s Gift, which draws on both Biblical and classical mythology.

2. Do you have a background in classical education (Latin or Greek at school or classes at the University?) What sources are you using? Scholarly work? Wikipedia? Are there any books that made an impact on you in this respect?

I did six years of Latin at high school, then another two years of Latin and two years of Greek at Sydney University. But my pleasure has always been literary and not scholarly – I read the works as a reader and a writer, not a scholar. Later in life I have joined Latin reading groups, through organisations such as the Workers Educational Association. As a writer I suppose I prefer to respond directly to the texts, word for word, as works of literature, as one reader to another, without mediation.

Courtesy of the Author.

3. How concerned were you with "accuracy" or "fidelity" to the original? (another way of saying that might be — that I think writers are often more "faithful" to originals in adapting its spirit rather than being tied down at the level of detail — is this something you thought about?)

I certainly did think about it when I was writing the plays, and I worked all the time with the original Latin texts, hoping to include as much detail as possible. But what I wanted most of all was to give children a sense of what the experience of reading Ovid might be like, that they would come away from the plays with an impression that these are not heavy, ponderous works, but witty, light, accessible and at the same time strange, dramatic and surreal. My primary motive is that children will have the pleasure of reading in the moment, but I’m also hoping that when they see the name Ovid anywhere in the future that they will associate it with laughter and wonder – and that they may be drawn to read more.

4. Are you planning any further forays into classical material?

Not specifically, but as you can see, I think I can’t help myself! The literature of the classical world seems inseparable from the way my mind works as a writer. I’m sure there will be more …

Prepared by Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Translation

German: Nicht jetz niemals, trans. Silvia Schröer, Uberreutr, 2012.

Slovenian: Izdaja, trans. Tamara Bosnič, Screcanja, 2013.

Summary

The Golden Day tells the story of a group of eleven schoolgirls from a private school in Sydney who are shocked when their teacher disappears on a school outing. ‘Today we will visit the gardens and think about death,’ says their teacher, Miss Renshaw, and she takes the girls to the beach, and into a cave, where she disappears. Beginning in 1967 and concluding in 1975, during Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War, the story includes reflection on the nature of war, personal and public politics, and the role of the individual in history. Allusions are made throughout to Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, and to Agamemnon: the girls study Thucydides, and one of them has a pet guinea pig called Agamemnon. Miss Renshaw’s disappearance throws the school into disarray, and forces the girls to think about their lives and their roles in personal and public politics and history. Has she been abducted, by Mr Morgan, the Aboriginal gardener, and poet who may be her lover? Has she been murdered? It is not clear. Echoes to the iconic Australian novel, Picnic at Hanging Rock (Joan Lindsay, 1967) pervade the novel: this time it is a teacher, not a student who goes missing; the setting is 1967, not 1900, but an old-fashioned Victorianism is present in the occasional rigidity of the school. Cubby, the protagonist through whose eyes the novel is filtered, reflects on her expectations of herself and other families (a fellow class-mate’s father may be having an affair with an older schoolgirl (Amanda, ‘fit-to-be-loved,’ thinks Cubby, referring to her Latin lessons) and the sense of an Australian society cut off from the history of the world by the sea, but also united by that sea with the rest of the world is important. Dubosarsky’s work is characteristically intertextual and intellectually so, and linking the story too with pictures such as Charles Blackman’s Floating Schoolgirl (1954), reflecting on the nature of youth and identity. The mysterious Miss Renshaw reappears, visiting four of the girls in a downtown café, explaining her absence as having gone on a Kombi-van tour of the country with her lover; however, Cubby notices that around her neck she is still wearing an amber pendant, a pendant that had been left behind in the cave. Is Miss Renshaw, therefore, a ghost?

Analysis

The Golden Day is an example of the resonance of classical reception to support reflection on aspects of history and of ideas about childhood. Through the references to Thucydides and Agamemnon, we see reflections on ideas to do with political power, the passing of time, the nature of war and empire. Through the setting in 1967 Australia, we see those references contextualise events such as Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War, its attitudes towards its indigenous people, and its attitudes towards adolescent girls, as well as political issues such as capital punishment. The amber pendant symbolises the passing of time and the eternal presence of the past. The Golden Day can be viewed as a post-colonial writer’s engagement with classical literary and historical references, brought together with important Australian literary and artistic references. Classical reception, filtered through history and literature from, or inspired by, the turn of the century (Henry Handel Richardson’s 1910 novel, The Getting of Wisdom; E. M. Forster’s 1924 A Passage to India, Joan Lindsay’s 1967 Picnic at Hanging Rock), merged with Australian ideas about geography (place in the ocean), art (see Charles Blackman’s ‘Floating Schoolgirl’) and Aboriginal culture and injustice towards Aborigines.