Title of the resource

Title of the resource in english

Publisher

Panholzer Uitgeverij, 1980

C. C. Buchner Verlag, 2008

Original language

Target and Age Group

Teachers, general public, classical oriented groups

Link to resource

Accessed on 19 August, 2020

Author of the Entry:

Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Second Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Ayelet Peer, Bar- Ilan University, ayelet.peer@biu.ac.il

Magda van Tilburg

Magda van Tilburg (born in 1954) is a Dutch children’s books illustrator and graphic designer. She studied Classical Languages and Literature at the University of Amsterdam (UvA) and then attended Gerrit Rietveld Art Academy to become an illustrator.

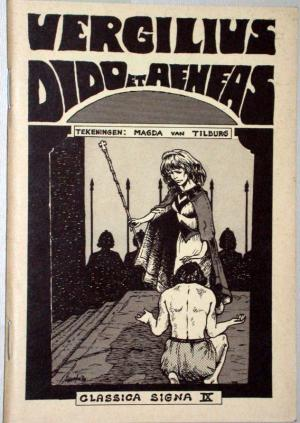

She created a series Classica Signa published by Panholzer - black-and-white cartoons based on classical Greek and Latin texts by Homer, Euripides, Herodotus, Virgil, Ovid, or Plautus. One of them - Dido et Aeneas was displayed at the exhibition Virgil across 2000 years at the British Museum. The series was remade into colour, digitalised and published by C.C. Buchner. It is available online, renamed as Antiqua Signa. After 30 years of her career as illustrator, the author also launched a website booxalive.nl, which promotes reading and the classical languages and contains digital books with illustrations by various authors, including those inspired by Antiquity.

At the moment the author is working on an English translation of Plautus' Curculio (which on booxalive is still in Dutch) and is planning to remake Alkestis by Euripides.

source: nl.wikipedia.org, booxalive.nl (accessed: September 30, 2019)

Courtesy of the Author

Questionnaire

1. Could you describe your experiences in education with Classical Antiquity?

From 1973 – 1978 I studied Classical Language and Literature at the University of Amsterdam (UvA), where I got my Bachelor Cum Laude. After that I went to the Rietveld Art Academy to become an illustrator.

Already in highschool I started to make classical graphic novels with the original ancient texts in the balloons. My first motive was, that I did not have any clue about translations. I always had a big fantasy about what the texts were saying, but in reality the texts said something else. By making drawings of what the texts really said, I could understand better what the stories were about.

With that history, after highschool I chose to study these two magnificent languages, to tame my fantasy and to teach my brain more abstract thinking.

During my university life, I extended my graphic novels to an entire series ‘Classica Signa’, with 8 titles, published by my late ex-husband (4 Latin titles/4 Greek titles).

After a 30-years career as a children's book illustrator I had to stop my studio due to chronic pain. Then I decided to create my own non-profit platform for all kinds of stories, to stimulate the modern youth to read more, and to promote Latin and Greek as fun languages with their immortal stories. So I transformed my titles to digital slideshows, with my translation in English. Now I call this series ‘Antiqua Signa’.

2. What are the language teaching methods and approaches of your choice

I don’t teach.

3. How and why do you choose your target groups?

The many classical orientated groups on Facebook are my main target, since I’m not able to do any active PR due to my health. Those groups include many teachers, and thus my work finds its way to classrooms etc.

4. Why should classical language teaching be paired with mythological education?

That’s the basis of our culture! Those immortal stories have to be kept alive!

5. How do you select the myths and cultural material to be incorporated in your works and how do you present them (do you strive for accuracy, with the cultural background of Antiquity, or do you rather contemporize their form, content or background to be relevant to the target group?)

I chose my titles from the programme I followed at the University. Before drawing each title, I try to research the original settings as well as possible (at the beginning of my work, there was no internet).

6. How do you choose the style of your illustrations that accompany the teaching material ?

I try to make my illustrations look as authentic as possible, with a touch of my own fantasy and humor.

7. Which task types do you employ to consolidate the myths?

With each digital title I also provide a section ‘Fun info’, where I explain some backgrounds of each story/myth.

8. Have you encountered any challenges in finding material on Ancient languages and culture and why do you think is important to popularize them?

I’m so very glad with the internet now and the exploding amount of old and new materials! I think nowadays more people get into mythology, because online there are no borders to get info. Also popular writers like Stephen Fry with his ‘Mythos’ and ‘Heroes’ promote the classics.

9. Are you planning any further forays into classical material?

I still have to translate 1 Latin title: Curculio by Plautus. I also have to redo the last translation, Euripides’ Alkestis. I hope this work will be done in mid-2020.

After that I hope to find a publisher who will produce 2 different volumes of novels (1 book with the 4 Latin titles/ 1 book with the 4 Greek titles).

* Much more about myself you can find on: booxalive.nl ‘in woord’ – I do hope your browser has a translation function…

* Please, feel free to take any image (covers and entire pages) from my site of the classic comic section, since my booxalive is also on a non-profit base!

* On my portfolio site you can find a survey of my children’s books from the last 30-years: magdavantilburg

Prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw (m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl).

Contents & Purpose

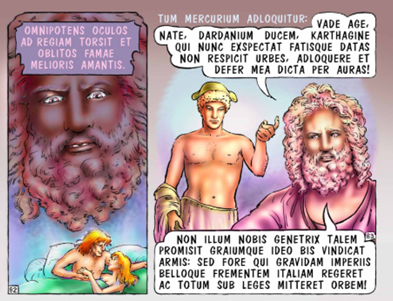

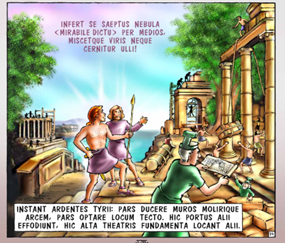

Dido et Aeneas is a Latin (bilingual Latin/English as a digital version) comic book based on mainly 4th book of Virgil’s Aeneis. The author presented the story of the characters using a comic she herself illustrated, with the text in the bubbles and the commentary written in Latin using phrases known to the reader from school class. The form of a comic makes the reading a lighter and better adapted to the young reader compared to the same original text as presented in a textbook in the form of classwork.

The story of Aeneas and Dido as told by Virgil and re-composed by Magda van Tilburg covers 55 pages. It begins with the famous mosaic from the Bardo National Museum depicting Virgil with one of the Muses, next to a map of places connected to the story; the poet is delivering the famous incipit Arma virumque cano, in which arma was changed to amor, since it is what the story of the comic revolves around. Having arrived at the Libyan shore, Aeneas and Achates meet Venus, who shows them the way to Carthage, just under construction. This is where Aeneas, by the gods’ will, experiences the delight of love and the bitterness of separation as they urge him to sail to Italy. Dido’s death as a consequence of her lover’s departure is depicted by the symbol of an extinguished candle with a trail of smoke. In the last scene Aeneas’ fleet reaches Cumae, the hero enters Sibyl’s cave and goes underground. The epilogue describes Aeneas’ meeting with Dido’s ghost in the Underworld, Dido ignores him and reunites with her deceased husband Sychaeus.

The text itself is only slightly modified so that it conveys a specific love story rather than Aeneas’ journey from Troy to Italy in 12 volumes. Because of those modifications, the storyline is cohesive as a story of two protagonists, but there is a certain trade-off - they cause the melody of the hexameter to be lost, which for some readers might also be an asset, as it might make translating the text easier. The text is composed in an approachable way and the translation provided on the side (the comic book’s author’s own English translation in the online version) allows the readers to verify the correctness of their own translation. Some more difficult terms are also explained in additional boxes.

The polished illustrations make the reading more interesting and help with understanding of the storyline and explaining the content. The drawings enliven the story with their suggestive colours, but at the same time they introduce the cultural background through the richness of details they depict (buildings, interiors, mosaics, friezes, furniture, vases or toiletries) or intertextual connotations they evoke (Virgil on page 3 refers to a mosaic from the Bardo National Museum, Jupiter on page 30 looks similar to Zeus of Otricoli (see below), Mercury on pages 30, 40 has the face of the statue of Hermes with Infant Dionysus by Praxiteles, Cumean Sibyl’s cave is depicted realistically, and Aeneas on page 13 is a synthesis of the Getty Kouros and the smiling Apollo of Veii). This intertextuality also concerns the reception of Antiquity - e.g. the scene from page 8 is only a slightly altered background of the painting Aeneas and Dido in Carthage by Claude Lorrain (see below), and the terrible Fama (Rumour) on page 28 also is present in the European culture - she appears in woodcut illustrations made for Renaissance editions of Aeneid, although on page 45 she refers rather to The Scream by Edvard Munch. Because of such use of recognised pieces of art in the comic, the reader is immersed in a wide range of the ancient culture’s influence, not only through the language. The comic can definitely enrich Latin classes, and bring Virgil’s legacy back to life.

Courtesy of the Author

Further comments

The comic was featured at the exhibition Virgil across 2000 years at the British Museum, 09/1982 - 02/1983; analyzed and displayed by Prof. Suerbaum at the exhibition Vergil Visuell at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, München, 1998.

Addenda

Courtesy of the Author