Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Marian Grześczak, O chłopcu, którym jesteś i ty. Warszawa: Nasza Księgarnia, 1981, 24 pp.

ISBN

Available Onllne

The text available at Polona (accessed: January 25, 2022).

Genre

Adaptations

Retelling of myths*

Target Audience

Children

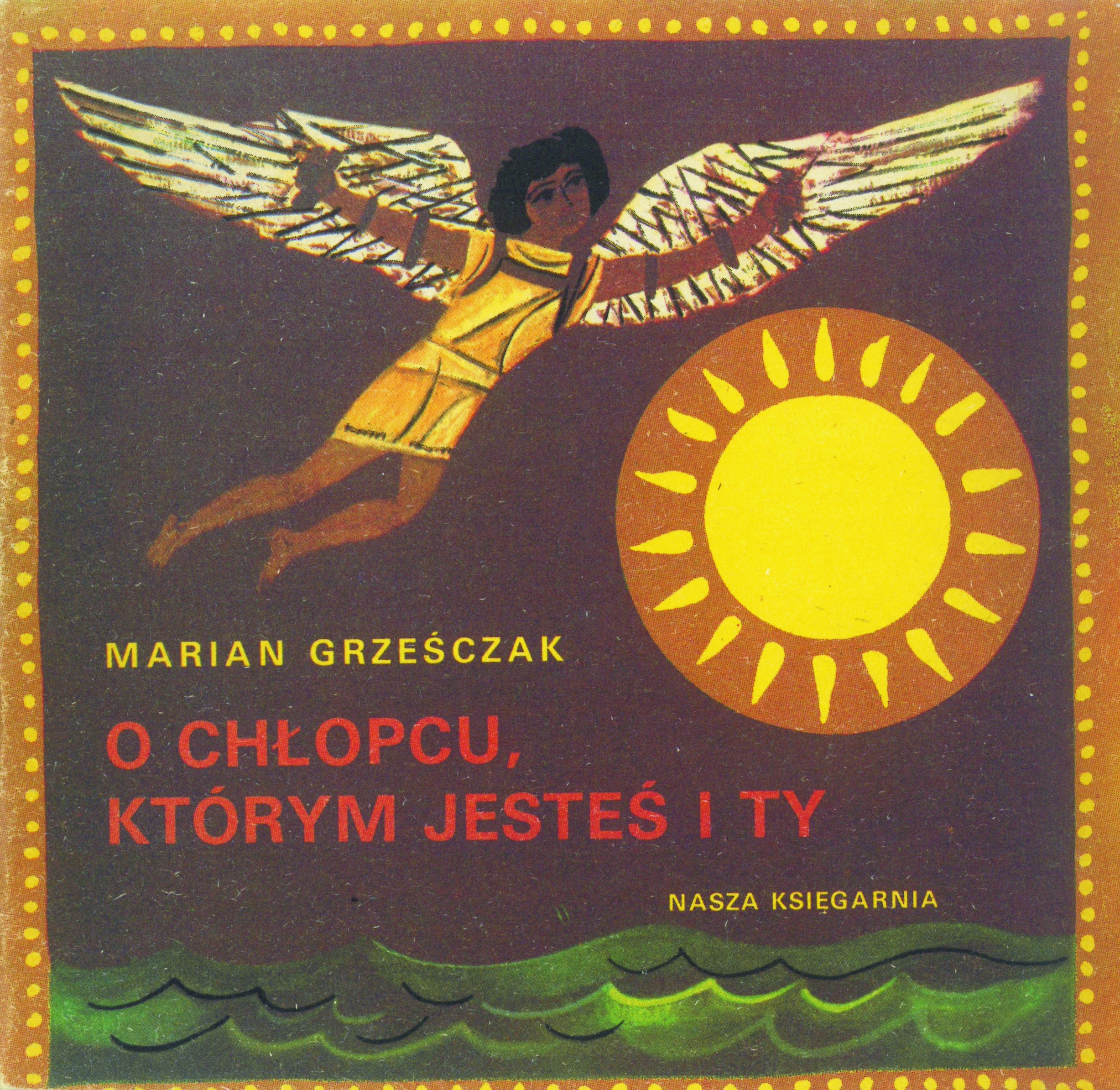

Cover

Courtesy of the publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Maria Karpińska, Univeristy of Warsaw, mariakarpinska@student.uw.edu.pl

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

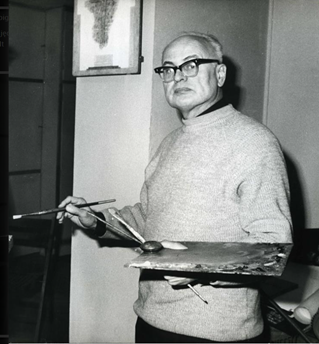

Photograph by Mariusz Kubik, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Marian Grześczak

, 1934 - 2010

(Author)

Marian Grześczak (1934-2010) was a poet, author of novels, short stories, and playwright; literary critic and translator; cofounder of the artistic group Wierzbak and of the Students’ Club Od Nowa where he was also the artistic director; laureate of many literary prizes; editor in magazines such as “Poezja,” “Scena,” “Tygodnik kulturalny” and “Twórczość” where he was an editor of the poetry column. Translator of Czech, Slovak, Croatian, Russian, and Israeli poetry. In the 1990s Polish consul in Slovakia and director of Polish Cultural Centre in Bratislava.

His best known book, Odyseja, odyseja [Odyssey, Odyssey], 1976, is based on the workers’ antigovernment protests in Poznań in 1956 where up to a hundred people were shot and killed. Many of his novels, as well as essays and poems refer to the Greek mythology, for example a multilingual volume of poetry called Atena strząsająca oliwki [Athena Shaking an Olive Tree], 2003, or Nike niosąca blask [Nike, the Bringer of Light], 2008.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: September 21, 2020).

"Grześczak Marian", in Lesław M. Bartelski, Polscy pisarze współcześni 1939–1991. Leksykon, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1995, 125–126.

"Grześczak Marian", in Jadwiga Czachowska and Alicja Szałagan, eds., Współcześni polscy pisarze i badacze literatury. Słownik biobibliograficzny, vol. 3: G–J, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 1994, 178–180.

Bio prepared by Maria Karpińska, Univeristy of Warsaw, mariakarpinska@student.uw.edu.pl

Photograph courtesy of Jacek Łoskot, the Artist's Son.

Zbigniew Łoskot

, 1922 - 1997

(Illustrator)

Zbigniew Łoskot (1922–1997) was a Polish painter, illustrator, printmaker and graphic designer. He was born in Warsaw, where he passed his high school final exam in clandestine courses during the Nazi occupation in 1942. He cooperated with the magazine Sztuka i Naród [Art and Nation]. He graduated from the Faculty of Painting at the Akademia Sztuk Pięknych im. Jana Matejki (Jan Matejko Academy of Fine Arts) in Cracow in 1949 (he finalized his degree in 1954). He was active in various areas and techniques of art, such as monumental wall painting, frescoes, sgraffito, mosaics, stained glass, easel painting (oil, tempera), woodcut, linocut or drypoint. He was well known for his sacred art – he designed and decorated many churches and chapels rebuilt and built after WW2, including the Primate’s of Poland chapel in the Warsaw Metropolitan Cathedral, all together, ten chapels and over twenty churches.

As an illustrator, he cooperated with many publishers, including Pallotinum, where he designed the cover and jacket of the Millennium Bible – the most famous 20th-cent. Polish edition of the Bible. Among other publishing houses, he worked for were also Iskry, KAW, PAX and Nasza Księgarnia, where he illustrated mainly books for children. He exhibited multiple times in Poland and abroad in individual or group shows. His works are held by the Vatican Museums, various Polish museums, Éditions du Dialogue founded in Paris by Polish Pallottines in 1966, and Pallottine collections in Rome.

In 1972, Nasza Księgarnia published Kolorowy świat – ilustracje w książkach „Naszej Księgarni” 1921–71 [Coloured World – illustrations in books by „Nasza Księgarnia”] including also works by Zbigniew Łoskot with the child reader in mind.

Source:

Official website (accessed: February 25, 2022).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

Daedalus and his inquisitive and lively son, Icarus, travel from Athens, from where they were banished, to Crete. Icarus dreams about being able to fly, so he and his father could travel much faster than they do, walking on the ground. In Crete, Daedalus builds a secret Labyrinth for the king Minos – only Icarus knows how to find the way out. In time, Daedalus becomes famous on the island – he invents new tools such as drill, plumb line and axe, but despite that he is sent to prison. We don’t know precisely why, the author only suggests that Daedalus didn’t finish his work on time, so maybe this was the reason for his arrest (taking into consideration the date of the publication of the book – 1981 – Daedalus’ imprisonment may be an echo of the arrests of dissidents in Communist Poland leading up to the imposition of Martial Law). Together, father and son, come up with the idea of building wings to get Daedalus out of prison. The boy visits his father and every time brings necessary materials to build the wings – feathers and wax. When wings are ready, Icarus and Daedalus escape from prison flying in the sky like birds. The boy is so excited and happy in the sky that he begins to fly higher and higher. His father tries to warn him that in the heat of the sun his wings may begin to melt, but Icarus, flying so high and so fast, doesn’t hear the warnings. Daedalus attempts to reach him, but it is too late – Icarus is already falling. Since that day, the distressed father is flying in the sky trying to find peace.

Analysis

The booklet was published as a part of the series Poczytaj mi mamo [Read to me Mom], which is a series of elaborately illustrated books for children in a small square format (first 16, then later, 21cm). Nasza Księgarnia started to publish the series in 1951; it became incredibly popular in Poland. The authors of the booklets are some of the most remarkable writers of children’s literature, such as A. Bahdaj, H. Bechlerowa, W. Chotomska, S. Grabowski, T. Kubiak, H. Łochocka, M. Musierowicz, J. Papuzińska, J. Porazińska, J. Tuwim, D. Wawiłow. About a Boy Whom You Also Are by Marian Grześczak truly fits well into the tradition while satisfying the requirements of the series – both the text and the graphic design are adapted to the needs of the child reader.

The adaptation of the myth about Daedalus and Icarus was given a title which does not refer to the myth. However, the cover illustration does: it depicts a boy as he approaches the sun with wings attached to his arms, below him are the sea waves. These elements allow parents of the reader to guess the boy’s identity, Icarus. The book cover attracts children and encourages them to read the book: since the incredible flying boy is a child just like the reader, perhaps it is worth reading the book and finding out what it is about.

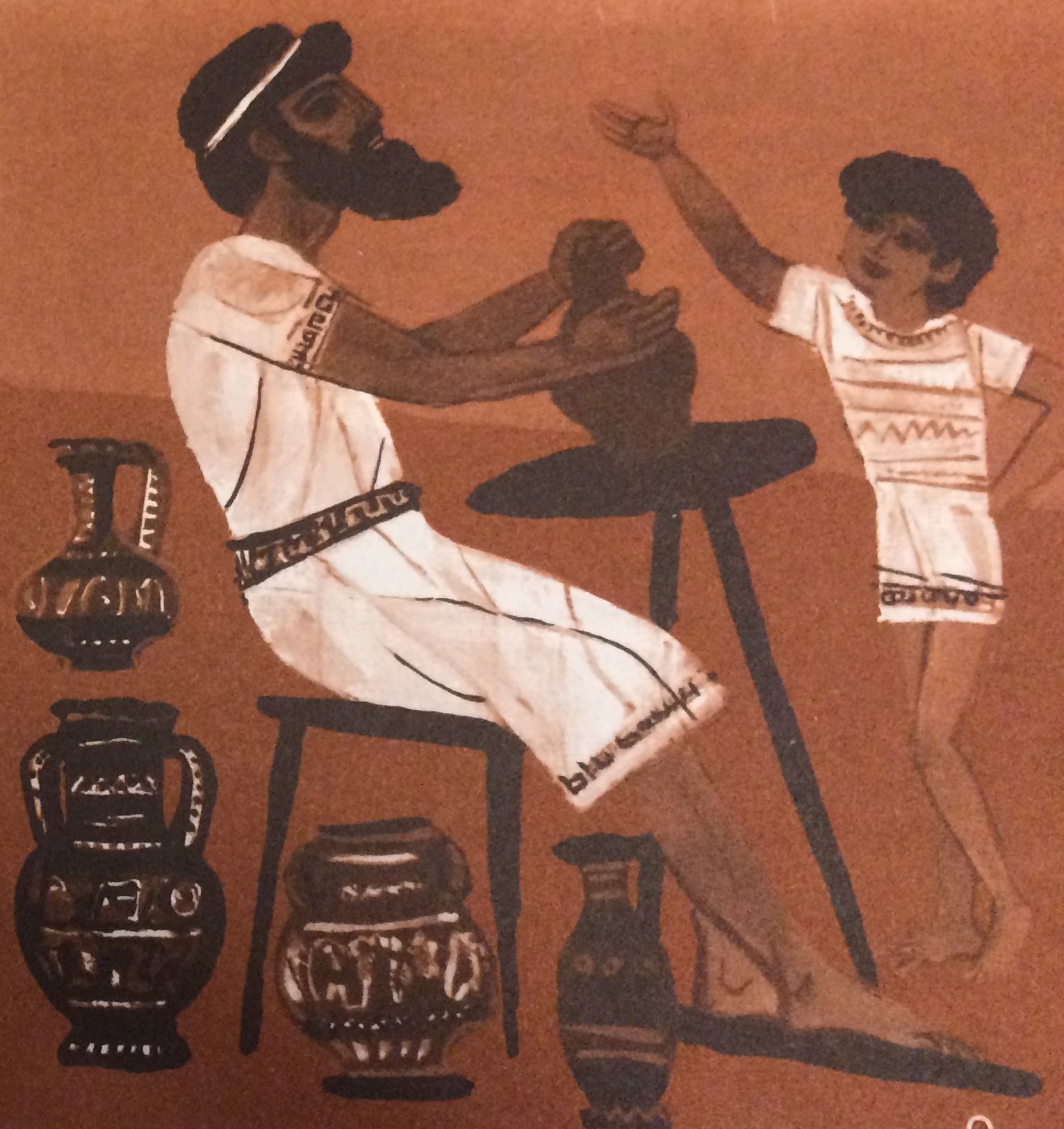

The myth, as described by Grześczak, presents two main characters: father and son. From the very beginning, we know nothing about the boy’s mother, but the strong bond between the characters suggests that she is absent. Daedalus is not described in the book as a brilliant inventor, but as a normal, ordinary father who loves his son and, despite working very hard and facing various adversities, always finds time to play with Icarus. At first, he works as a potter, tries to engage his son in working with clay and, through playing and working together, teaches him his wisdom and the facts of life, e.g. "co zbudujemy dziś, nie będzie do zrobienia jutro" [what we build today, will not have to be done tomorrow] (p. 4). Daedalus always takes care to do his job as well as possible. Having been banished from Athens, never to return, he travels with Icarus, and together they explore new landscapes, cities and meet new people. As he changes his profession to building and sculpting, he brings a certain lightness to the objects, so as to please his son, and as he later once more changes his profession to carpentry and woodwork, it is Icarus who inspires him to invent tools to make processing the wood easier. In each of his actions/activities, Daedalus expresses a lot of love and care for the boy. The bond between them brings to life a special project, which is completed in secret and hidden from the guards – they build a tool allowing them to escape and, at the same time, make Icarus’ childhood dreams of flying come true. Eventually, as the son is lost, the father flies away in an eternal flight looking for something in the vastness of the world to soothe his pain.

The character of Icarus, the boy with whom the child reader is to identify, is 6 years old and has the characteristics of a typical child of that age: he loves his father, but doesn’t like being called the “little one”, he is lively, a bit impatient, curious of the world and sensitive to the beauty of nature. By observing his surroundings, he is looking for answers he cannot wait to obtain, such as where the wind comes from. His deepest fascination is flying – the theme of wings evoked by the boy repeatedly occurs from the very first pages of the book. He is interested in anything that has wings: bees, birds; he considers flying to be quick, and marching, slow. While Daedalus is imprisoned, he cannot deal with the separation from his father and goes out of his way to see him and to spend time with him. The longing is what breeds his ingenuity – he bribes the guards with fruit and roast meat so that they allow him to visit Daedalus, and then he helps him run away by supplying the necessary materials to build the wings and works with him side by side. In this moment of the trial he is sensible and mature: as they construct the wings "każdy z nich milczał, ale każdy wiedział, ku czemu zmierzają" [both of them were silent, but both knew where they were heading] (p. 17). There is no mention of Icarus disobeying his father or ignoring his advice. His fall and death are the results of not being able to hear the warnings during the flight rather than of purposefully ignoring Daedalus’ words in a state of blind joy and exaltation produced by the realization of his dream and the feeling of freedom.

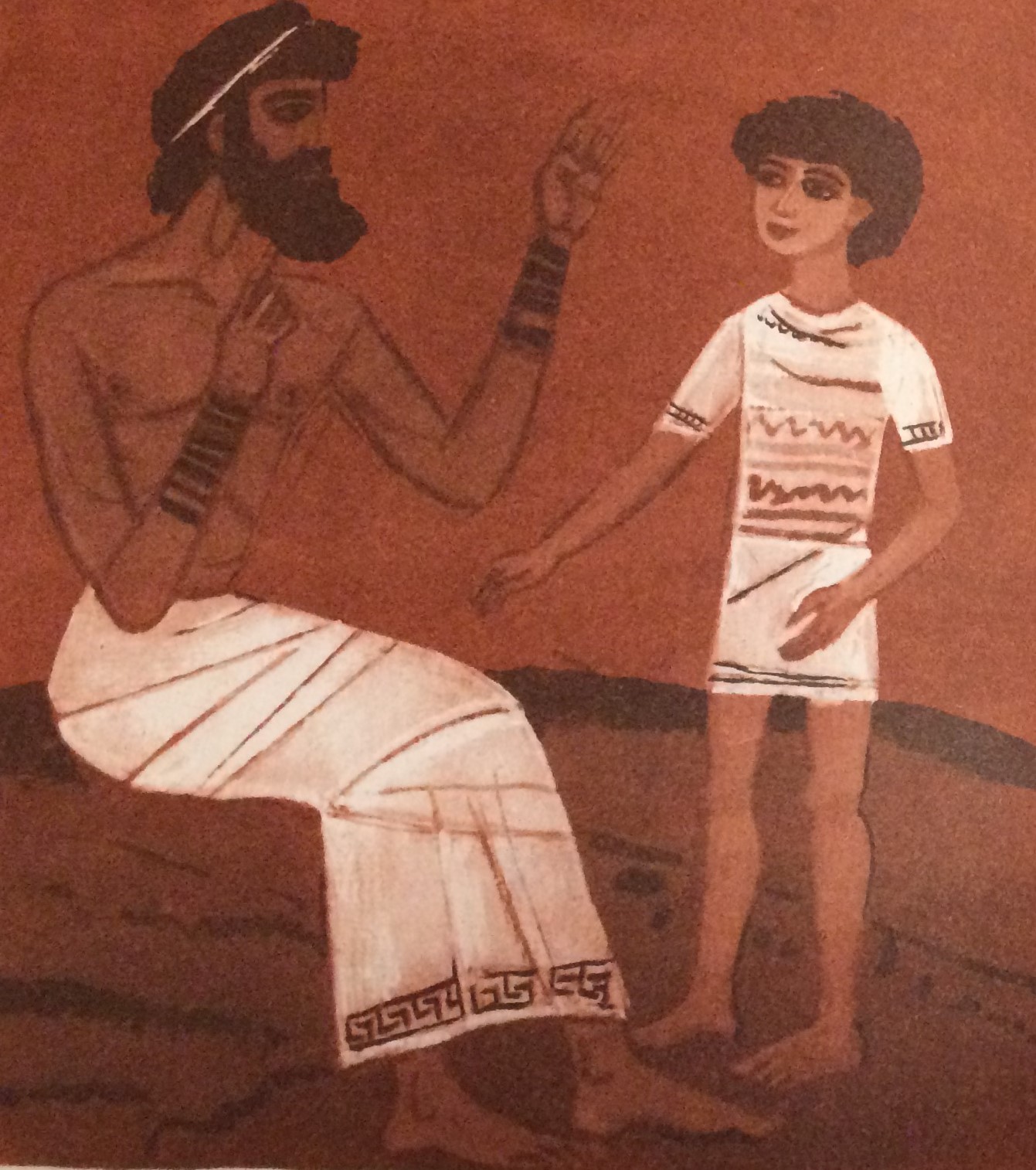

What is also important to note is the interesting graphical depiction of both characters. In all of the illustrations, they are shown together in the middle of different activities, which underlines their mutual bond. The only exception is the illustration of Icarus when he bribes the prison guards with a piece of meat. The illustrator shows Icarus to be a slim boy wearing a short tunic, with a slightly larger head, a smooth face and big pronounced eyes, a style similar to the contemporary manner of drawing children. Interestingly, the depiction of Daedalus is different. In all of the pictures he is shown from profile and his appearance, shape, pose, and gestures, recall the characters usually found on Greek pottery (which are also shown in the book – Daedalus is, in fact, a potter). Moreover, about half of the book’s illustrations are also presented in the colour scheme found on vases.

Illustrations courtesy of Jacek Łoskot, the Artist's Son.

Out of necessity the myth was shortened and simplified (the book has 24 pages of modest size, half-covered by illustrations), although a few specific aspects should be explained. When the book refers to Daedalus’ unfriendly circumstances: his exile from Athens and imprisonment on Crete, the reader does not know why that happened. Daedalus is a decent, hard-working man, who tries to work as scrupulously as he can; it does not seem he could be guilty of any deed punishable with exile or imprisonment. A possible reason for the latter is hinted at: a delay in the construction of a ship – but it does not seem to be a sufficient reason, and it probably is not. Icarus does not understand why his father is arrested and considers it unfair. The situation could be familiar to Polish children whose family members were arrested by the communist authorities during the wave of political repressions – without any punishable cause, often without a charge. Raising such a complicated issue through the agency of the myth could help the child understand that such situations also happen to other children whom you also are.

Further Reading

Author's official website (accessed: September 21, 2020).

"Grześczak Marian", in Lesław M. Bartelski, Polscy pisarze współcześni 1939–1991. Leksykon, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1995, 125–126.

"Grześczak Marian", in Jadwiga Czachowska; Alicja Szałagan, eds., Współcześni polscy pisarze i badacze literatury. Słownik biobibliograficzny, vol. 3: G–J, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 1994, 178–180.

Illustrator's official website (accessed: February 24, 2022).

Addenda

Illustrations courtesy of Jacek Łoskot, the Artist's Son.