Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Justyna Jastrzębska, ed., Bogowie greccy i rzymscy. Najważniejsze wiadomości z mitologii, "Bibljoteczka Młodzieży Szkolnej" 136. Warszawa: Nakład Gebethnera i Wolffa; Kraków: G. Gebethner i Spółka, 1911, 34 pp.

Available Onllne

polona.pl (accessed: December 18, 2020)

Genre

Myths

Target Audience

Crossover (Children, teenagers)

Cover

Retrieved from Polona, public domain.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Małgorzata Glinicka, University of Warsaw, muktaa.phala@gmail.com

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Justyna Jastrzębska

, 1889 - 1944

(Author)

A historian, educator; she authored the following books: Bogowie greccy i rzymscy. Najważniejsze wiadomości z mitologiii [Greek and Roman Gods. The Most Important Information from Mythology], 1911; Wojny Greków z Persami [The Graeco-Persian Wars], 1912, and Dzieje powszechne. Podręcznik dla seminarjów nauczycielskich [General History. Textbook for Teachers’ Colleges], ed. pr. 1920 (a popular book; subsequent editions: 1922, 1925). Translator of French historical and educational books.

Bio prepared by Małgorzata Glinicka, University of Warsaw, muktaa.phala@gmail.com

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

The author highlights the differences between Greek and Roman myths. According to her, Greek mentality is characterized by abundant fantasy and imagination, able to create a magical and complex world of gods and heroes, filled with various creatures, deeds, adventures, strong feelings, and impressions. No other nation produced such rich collections of myths and legends driven by natural phenomena and resulting in images of beauty and harmony. Greek gods are not ideals or symbols but beings similar to humans in shape, feelings, merits, and faults. On the other hand, Romans were farmers without excessive imagination and need for conceptualization of ideas. They preferred to structure a coherent system of cult than to imagine stories of gods. Under the Greek influence, the Romans finally adopted the main personalities of gods but their indigenous legends remained rudimentary.

Analysis

The author prepared a short compendium of mythological knowledge for children, a kind of guide for young readers. She intended to introduce children to the Greek and Roman worlds and facilitate understanding of who was who in the ancient world of gods. She divides the text into two parts: about Greece and Rome. In each part, she first gives some general information, and then more specific details about specific gods and myths related to them.

The author uses language which mirrors her preferences and judgement. It is obvious that she admires Greeks and their great creativity and fantasy, from the way she writes about them in the language of poetical comparisons, with a slight hint of nostalgia ("The sun rises, we say today – but according to Greeks it’s the god Helios on his golden chariot drawn by his fiery steeds who emerges from behind the Ocean", p. 1). She thinks about the Greeks in categories of beauty, harmony, charm and serenity (pp. 1–2). About the Romans, she writes oppositely, in a simplified manner and sees in them as just farmers and soldiers who worshipped power and systematized the cult in detail because they lacked the fantastical imagination to do otherwise. According to her, "they received anthropomorphic gods from the Greeks and had completely forgotten their own gods since the second Punic war: they identified with the lively, young, and beautiful world of Greek gods" (p. 28). The author also mentions and cites Greek literature, e.g., quotes from Homer and Hesiod when talking about Greeks, but also, interestingly quotes Ovid, despite his Roman, read pedestrian, perspective. In the section about the Romans, however, there is no mention of literature, as if they had none.

Jastrzębska uses a pseudo-scholarly approach. When describing a god, she first tries to convince the reader about her credentials in the subject starting ab ovo from the most ancient and primary form of the character, his or her prerogatives, symbols, forms of the cult, etc. and then shows how it changed over time. For example, the goddess Athena was at first regarded as a formidable goddess of the tempest and war, but later worshipped as the goddess of wisdom, discipline, and order. Similarly, Hades was at the beginning the god of growing crops, and then later only the god of the Underworld. However, the author’s mythological knowledge seems sketchy, there are a few errors or mistakes not verified in primary sources. Considering that the ancient sources have not changed since 1911 and the current public awareness of Homer and Hesiod seems less extensive than it was at the time, the errors cannot be explained by new discoveries and Jastrzębska could have easily avoided them. When she writes about Athena, she describes her as wearing a coat made from hide with the attached head of the Gorgon Medusa slayed by Heracles (p. 16) which interferes with the common version of the myth of Perseus. Jastrzębska also provides no attribution to one of the versions of the origin of Aphrodite. She mentions a Homeric version in which the goddess is a daughter of Zeus and Dione without identifying Iliad as the source. She correctly attributes to Hesiod the version of Aphrodite being born from the sea foam near Cyprus, but omits the origin of the foam, which can be easily understood in a booklet aimed at children. She makes an outright mistake calling the messenger of Greek gods who descended to Earth on a rainbow, Isis and not Iris.

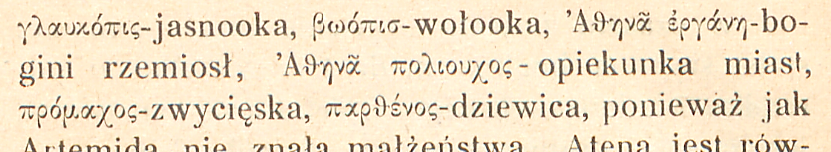

There is also only one unusual fragment (p. 18) where she gives Athena’s epithets using ancient Greek, unfortunately with errors in vowel length, hence in the type of accent (the words γλαυκῶπις, βοῶπις, in fact, mainly used to describe Hera, and πολιοῦχος). Curiously, this approach is not applied in case of the other gods, as if they did not have their own ancient epithets, and when exceptionally, an epithet is provided, it is transcribed in Latin alphabet (e.g., Aphrodite Anadyomene).

True to her times, while suggesting to the reader that the image of gods mirrors humans with all their ups and downs, she censors and tries to gloss over the less laudable aspects of the Greek gods. Their discreditable deeds are omitted or mentioned casually, without any emphasis. For example, Zeus is presented as a judge (flood as a punishment upon humans is briefly mentioned), but a fair one – just, righteous and clement; the guardian of order, oath and hospitality; the ruler of rain, snow, and hailstorm, but first of all, of life-giving rain because of that quality called gold (pp. 8–9). There is no mention of his love affairs, rage or outbursts of anger. When the author mentions Io, she uses an euphemism: Zeus paid attention to her beauty and just because of that the jealous Hera took revenge on the girl (p. 10). When Hermes, Apollo, Aphrodite, and Dionysus are presented, Zeus is casually mentioned as their father but the fact that they were born out-of-wedlock is ignored.