Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

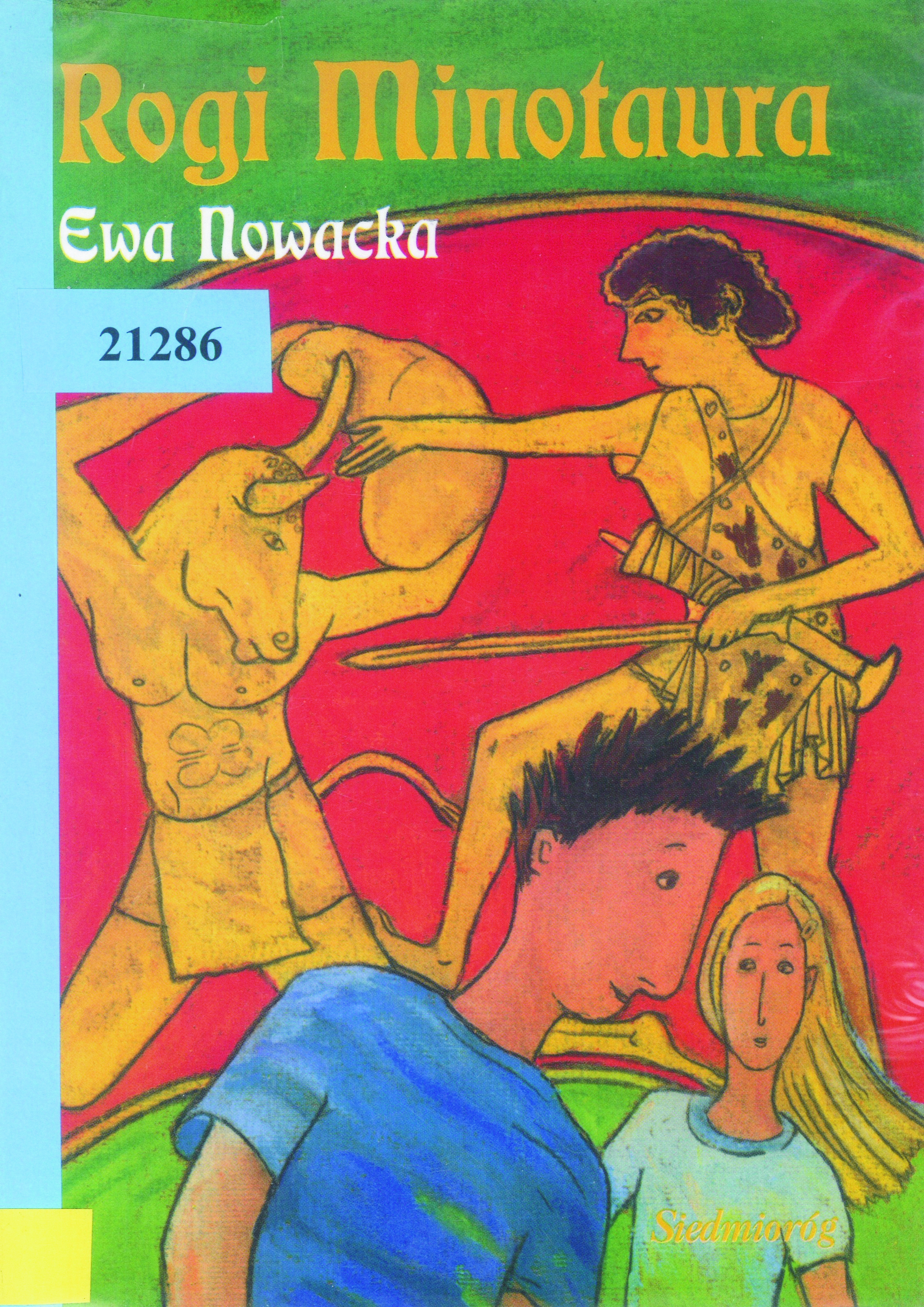

Ewa Nowacka, Rogi Minotaura. Ill. Marzena Zacharewicz, Wrocław: Siedmioróg, 1998, 80 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Time-travel fiction

Target Audience

Crossover (Children, teenagers, young adults)

Cover

Courtesy of the publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Joanna Kozioł, University of Warsaw, joasia7777@interia.pl

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

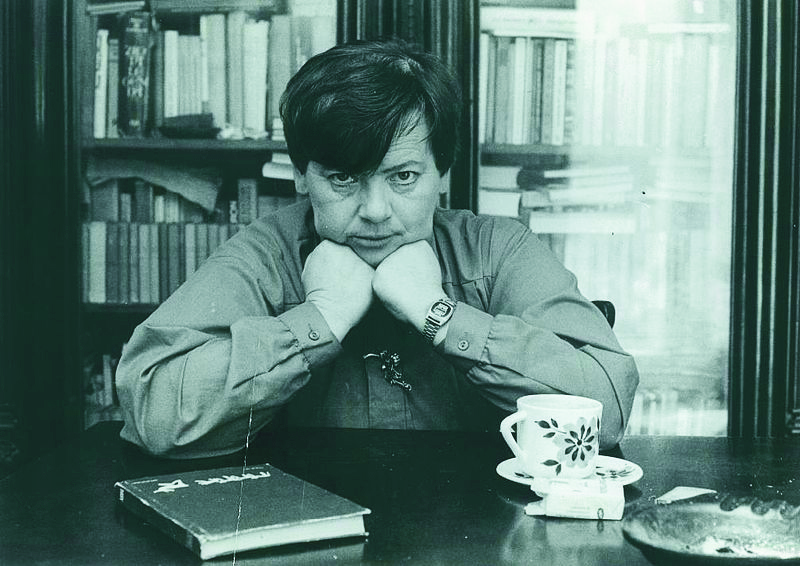

Ewa Nowacka, photograph by Fzsr, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons (accessed: December 29, 2020).

Ewa Nowacka

, 1934 - 2011

(Author)

A novelist, critic and essayist, winner of numerous national and international awards. For lifetime literary achievement she was awarded Janusz Korczak International Literary Prize, medal of the Polish Section of IBBY, the Commander’s Cross of the Order Polonia Restituta, medal of the Commission of National Education, and the Gloria Artis Medal for Merit for Culture (Gold Class). She wrote about 50 books, mostly for children and adolescents. The author of a bestselling novel Małgosia contra Małgosia [Maggy contra Maggy], 1975, about a 17–year–old heroine living in 20th century Warsaw who is suddenly transported into the 17th century. Nowacka felt at home in Pharaoh’s Egypt, Roman Empire and in modern times. For many years she worked at the Polish Radio and produced many radio-plays for children and young adults.

Sources:

lubimyczytac.pl (accessed: December 29, 2020).

pl.wikipedia.org (accessed: December 29, 2020).

Danuta Świerczyńska-Jelonek, "Różne światy powieści Ewy Nowackiej", Guliwer 3 (2004): 5–13.

[Obituary], PAP [Polish Press Agency], Zmarła autorka popularnych książek dla młodzieży, wiadomosci.wp.pl (accessed: December 29, 2020).

Bio prepared by Sebastian Mirecki, University of Warsaw, smirecki@student.uw.edu.pl

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

Ewa Nowacka, Byk Apis pozdrawia kotkę Pusię, Wrocław: Siedmioróg, 1998.

Ewa Nowacka, Proszę bilet na wieżę Babel, Wrocław: Siedmioróg, 1998.

Ewa Nowacka, Jak okiełznać wronego rumaka, Wrocław: Siedmioróg, 1999.

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

This is the third book in the series Skrzydła czasu [The Wings of Time]. Paweł and Karolina are cousins. When Karolina one day came to Paweł’s house, she became very interested in a television game The Wings of Time. The game somehow transported them to the ancient island of Crete. Karolina was delighted by this turn of events and went to swim in a bay. When she hurt herself, a boy came and offered to help her. This boy turned out to be Icarus. Icarus brought them to Daedalus’ (his father’s) house. Paweł and Icarus liked each other immediately; Icarus fell in love with Karolina.

One day Paweł and Icarus went for a walk during which Icarus showed Paweł the volcano Santorini and Minos’ bulls. When they came back, Karolina was not there. Daedalus told them that Karolina went with the Great Priestess who saw her exercising in the garden. Paweł and Icarus went to the Labyrinth to ask the princess Ariadne for an opportunity to see Karolina before the day of the Great Festival. They managed to see her training with the other girls and boys for the competition (jumping over the bulls) scheduled to take place during the Festival. Icarus warned Karolina that the competition was dangerous but she didn’t want to come back with them.

Minos was fascinated by Karolina’s exercises and wanted her to stay on Crete. Paweł was scared. He accidentally returned to his own home and time but then decided to go back for Karolina. The day of the Great Festival finally came. Paweł was terrified and shocked when he watched the competition. Karolina competed last. At the beginning, she did very well, but then began weakening. Paweł took princess Ariadne’s purple scarf and rushed to help Karolina. The angry bull was taken by the guards. Paweł was arrested and jailed in the dungeon of the Labyrinth in Minos’ palace. In the end, the princess Ariadne came to him and gave him a ball of thread which allowed him to escape. Once he was free, Paweł met Karolina and they both decided to go home as soon as possible. Icarus found them a boat, they said good bye to him and sailed close to the volcano Santorini. An eruption of the volcano brought both of them home.

Analysis

Minotaur’s Horns uses the idea of time travel to briefly show ancient myths and culture in a manner that is entertaining to a young reader. As the main characters are transported to ancient Crete, the reader learns about the Minoan culture through the adventures of the protagonists.

The action is set during the childhood of mythological figures such as Icarus and Ariadne. This narrative device allows Paweł and Karolina to make friends with Icarus and at the same time, helps the young Polish reader to identify with the characters.

Minoan Crete is reconstructed with details of beautiful Mediterranean landscapes including characteristic plants and animals and with fine points of an opulent ancient culture known from archeological discoveries and ancient sources supplemented by the creativity of Nowacka herself. There is an abundance of information about everyday life and its organization. The reader sees the beautiful and famous land, rich, well organized, its wealth due to the Cretan harvests and the hard work of the inhabitants. The palace of the ruler is splendid and planned like no other in the world, as it was designed and built by the master architect, Daedalus. The lower level is constructed like a maze for strategic reasons, which could be the impulse for the myth of the Labyrinth. The higher level, however, is luxurious, full of harmony and beauty. The child reads about paintings, music, dance, oral tradition (here compared to television), the arena, temples and sacrifices, the way of counting crops or the apparent lack of a writing system comparable to other cultures. Some of the information provided, for example, the description of rituals connected with the Great Festival, is based on the Minoan frescoes and enriched by the author’s imagination.

The Minoan scenery is used to present the main plot, which is interestingly an alternate origin of the Cretan myth: the main characters of Nowacka’s novel are just like the original heroes of the myth we know today. Daedalus and his son must remain on the island on Minos’ orders. Daedalus is suspected of being a wizard or sorcerer; people whisper that he steals secrets from the gods. The ruler restricts Daedalus’ liberty to prevent him from building a similar palace for somebody else; he is a possessive man who desires fame, wealth and prestige and refuses to share it with others. He wants to own the only building of this kind in the world. In private, without the bull mask with golden horns, worn in public, Minos is quite an average man. When Icarus leads Paweł to Ariadne, he tells him that rumours spread by people on other islands and in continental Greece about the Minotaur, a man with bull’s head, supposedly living in the palace, are not true. The name of Theseus is completely unknown to Icarus and the reason why becomes clear when Ariadne with her thread helps Paweł to escape from the dungeon. That is how the myth was born and adorned by posterity with characters more familiar to the ancient Mediterranean than Paweł and Karolina from the distant future.

The adaptation of the text for a child reader is evident not only in the main story but also in the general approach of explaining issues which could be more difficult or unknown to children. Outlandish elements are compared with our reality to allow children to understand and “tame” them. Paweł compares Mr. Daedalus to his uncle Marcin to reduce the temporal and cultural distance. He also highlights the similarity of the spectacle produced during the festival, in which young people get hurt, injured or killed, to the Spanish corrida he learned about from his uncle Roman. The uncle said that he did not like it because he was sorry for the hurt, tired and exhausted animals. When the young people are showcasing their skills in the arena, a performance which may end in their death, Paweł wonders, as do the readers of the story, why all these normal, ordinary people – fishermen, shepherds, winemakers – enjoy such bloody and cruel entertainment. He considers it should not be allowed and fails to understand why people, who personally know all these girls and boys, would not refuse to watch them get hurt or die.

Interestingly, back home, Paweł checks the Minoan culture and the eruption of the volcano on Santorini, which he experienced, in his encyclopedia: the only inaccurate item is the lack of writing. However, the author cautions that the “dispute about Phaistos disc and the so-called Linear script continues.” A seemingly strange quotation from an encyclopedia, as the decipherment of Linear B writing published by Chadwick and Ventris many years earlier (1953) has been recognized by scholars worldwide. On the one hand, Paweł’s encyclopedia may have been a pre-1953 edition. On the other, children for whom writing is strictly connected to letters, are unlikely to intuitively grasp principles of a different system and accept that there could be writing without the letters.

Further Reading

Chadwick, John, The Decipherment of Linear B, Cambridge University Press, 1990 [1958] (accessed: December 29, 2020).

Graves, Robert, The Greek Myths, vol. 1–2, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1955.

Graves, Robert, Mity greckie, Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1982.

Świerczyńska-Jelonek, Danuta, "Różne światy powieści Ewy Nowackiej", Guliwer 3 (2004): 5–13.

Ventris, Michael, Chadwick, John, "Evidence for Greek Dialect in the Mycenaean Archives", The Journal of Hellenic Studies 73 (1953), 84–103 (accessed: December 29, 2020).

Cracking the code: the decipherment of Linear B 60 years on, University of Cambridge, 13 October 2012. cam.ac.uk (accessed: December 29 2020).