Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

ISBN

Available Onllne

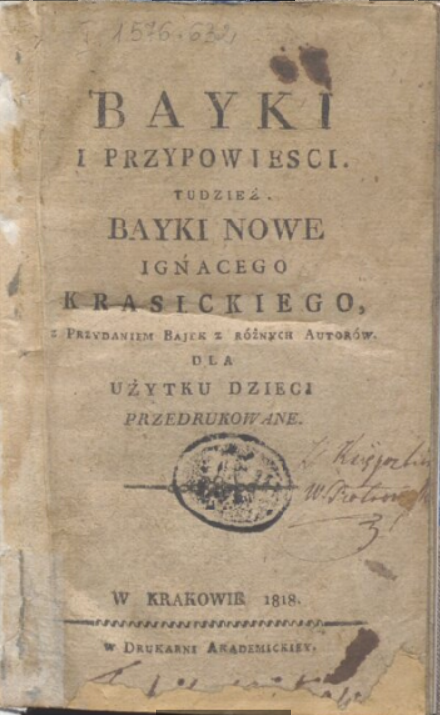

"Kruk i lis" in Bayki i przypowieści tudzież bayki nowe Ignacego Krasickiego z przydaniem bajek z różnych autorów dla użytku dzieci przedrukowane, Kraków: w druk. Akademickiej, 1818. Available at Polona (accessed: September 26, 2022).

Genre

Didactic fiction

Fables

Instructional and educational works

Poetry

Target Audience

Crossover

Cover

Cover of Bayki i przypowieści tudzież bayki nowe Ignacego Krasickiego z przydaniem bajek z różnych autorów dla użytku dzieci przedrukowane from 1818. Retrieved from Polona (accessed: September 26, 2022). Public domain.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Zofia Górka, University of Warsaw, vounaki.zms@gmail.com

Analysis: Karolina Anna Kulpa, University of Warsaw, k.kulpa@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Ignacy Krasicki, portrait by Antoni Oleszczyński, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons (accessed: June 28, 2018).

Ignacy Krasicki

, 1735 - 1801

(Author)

A poet, novelist, Bishop and Duke of Warmia, then Archbishop of Gniezno. One of the most important authors of the Polish Enlightenment. Born in an aristocratic family and very well educated. Between 1759 and 1761 studied in Rome. Friend and collaborator of king Stanisław August Poniatowski, as well as a senator. Buried at Saint Hedwig’s Cathedral in Berlin, but in 1829 his remains were transferred to Gniezno Cathedral in Poland. The important aspects of Krasicki’s literary style are irony and didacticism. He is considered master of the epigrammatic fable. Many contemporary and later authors were influenced by his works. Main titles: two mock–heroic poems Myszeidos, 1775, and Monachomachia, 1778; Pan Podstoli [Lord Steward], parts 1–2: 1778–1784, part 3: 1801; Mikołaja Doświadczyńskiego przypadki [The Adventures of Mr. Nicholas Wisdom], 1776 — the first Polish Enlightenment’s novel; an historical epic poem Wojna chocimska [The Chocim War], 1780; Bajki i przypowieści [Fables and Parables], 1779.

Source:

Kadulska, Irena, Ignacy Krasicki 1735–1801, literat.ug.edu (accessed: June 28, 2018).

Bio prepared by Zofia Górka, University of Warsaw, vounaki.zms@gmail.com

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

The Raven and the Fox is one of the original fables by Aesop. The main characters of the fable are a cunning fox and a vain raven with a tidbit in its beak. In order to get the food (most authors, incl. Krasicki, mention a piece of cheese, however, one of the preserved versions of Aesop’s fable mentions meat), the fox uses a ruse. Knowing that the raven is greedy for compliments, the fox encourages him to sing. As the raven begins to caw, the tidbit fells from its beak straight into the fox’s mouth.

Analysis

At the beginning of the 1st century a.d., the poem together with other Aesopian fables was adapted into Latin by Phaedrus from the Greek prose into Latin iambic trimeters. In the 17th century, Jean de La Fontaine published between 1668 and 1694 a French version of Aesop’s fables based on Phaedrus’ adaptation*; it greatly influenced Krasicki’s fables. Similarly to Phaedrus and La Fontaine, Krasicki decided on a rhymed version. However, there is a note saying: Based on Aesop’s version.

In Krasicki’s fable, like in Phaedrus, lyrical ego gives advice about unpleasant consequences for people who listen to insincere adulators. At the end of the story, the raven is tricked into relinquishing the cheese which is immediately snatched by the fox who escapes with his trophy. In Phaedrus’ version, the raven deplores the outcome, in Krasicki’s story, we don’t know if he understood that he was outfoxed. In contrast, in La Fontaine’s fable, the fox doesn’t escape after taking the raven’s cheese, but he gives his victim advice about trusting flatterers because if we do, we often pay the price while the flatterer gets his reward. In Krasicki’s version, the fox also flatters the raven comparing him to Phoenix, the mythological firebird (line 9).

Krasicki’s fables, including The Raven and the Fox, like fables in general, had an important didactic aspect. The moral of a fable uncovers human weaknesses - vanity in this story, or conceit in the fable entitled Gęsi [Geese] about geese, who were bragging about having saved Rome and as a result of their behaviour, were eaten by wolves. Ignacy Krasicki has been a very popular writer since 19th and in Poland, his fables were compulsory reading for children in primary school.**

* First edition published by Pierre Pithou at Troyes in 1596, according to J. E. Sandys, A History of Classical Scholarship From the Revival of Learning to the End of the Eighteenth Century in Italy, France, England and the Netherlands. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011, p. 192.

** Core Curriculum for Polish language instruction by the Ministry of National Education of the Republic of Poland, at www.men.gov.pl/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/podstawa-programowa-–-jezyk-polski-–-szkola-podstawowa-–-klasy-iv-viii-.pdf, accessed: 17.10.2017.

Further Reading

Abramowska, Janina, "Bajki i przypowieści Krasickiego, czyli krytyka sztuki sądzenia", Pamiętnik Literacki 63.1 (1972): 3–47.

Addenda

Entry prepared on edition: Ignacy Krasicki, Kruk i lis [The Raven and the Fox], in: Bajki [Fables]. Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1975, 106.