Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

James Matthew Barrie, Peter and Wendy. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1911, 267 pp. (plus 11 full-page plates by F. D. Bedford)

ISBN

Available Onllne

Peter and Wendy is widely available online, but Open Library (below) has a carefully scanned copy of Charles Scribner Son’s 1911 edition.

Peter and Wendy, Open Library (accessed: November 30, 2021);

Peter and Wendy, Gutenberg Project (accessed: November 30, 2021);

Peter and Wendy, Literature Project (accessed: November 30, 2021);

Peter and Wendy, Wikimedia Commons (accessed: January 13, 2022).

Genre

Action and adventure fiction

Fantasy fiction

Target Audience

Crossover (At the time of first publication )

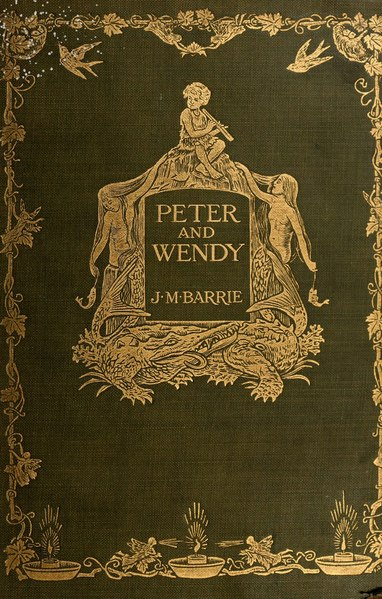

Cover

Cover retrieved from Wikimedia Commons (accessed: January 13, 2022). Public domain.

Author of the Entry:

Michelle Wyatt, University of New England, michellewyatt5@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

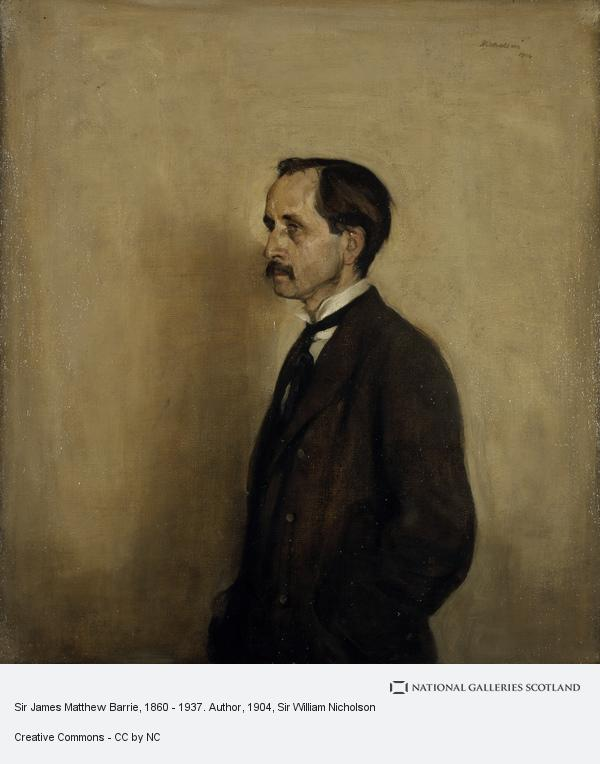

Portrait by Sir William Nicholson. Retrieved from National Galleries Scotland (accessed: January 13, 2022). Creative Commons CC BY-NC.

James Matthew Barrie

, 1860 - 1937

(Author)

James Matthew Barrie was born on the 9th May 1860 in Kirriemuir, Scotland. He was the ninth of ten children, and the third son, born to David Barrie, a handloom weaver, and Margaret Ogilvy. His elder brother David died when James was six, and after his death, James endeavored to take his place in his mother’s affections. The events surely shaped the writer he was to become. He spent many hours beside his grieving mother, where they read such stories as Robinson Crusoe (1719) and the historical novels of Sir Walter Scott. He was drawn to adventure stories, and his mother also shared with him the story of her own youth. Margaret had taken over care of her household, including care of her younger brother, when she was just eight years old, because her mother had died. It is generally considered that the idea of a young Margaret keeping house came to influence Barrie’s creation of Wendy, and the memory of his dead brother, a boy forever suspended in time, came to inform the life of Peter Pan.

Barrie attended Dumfries Academy from the age of thirteen, and this is where he was first publicly acknowledged for his writing. Inspired by the adventure tales in penny dreadfuls (popular adventure stories), Barrie wrote Bandelero, The Bandit (1877), a short play for the drama society he created with a schoolmate. The play offended the morality of a minister, who admonished it in the local paper, but Barrie and his friends successfully sought support for the work from some distinguished members of theatre and from the London newspapers. He shortly thereafter began studying literature at Edinburgh University in 1878, and here he received his Master of Arts in 1882. During his time at Edinburgh University, he wrote for the Edinburgh Evening Courant as a freelance drama critic, and then, after graduation, early in 1883, he began working as a staff columnist for the Nottingham Journal. He then returned to Kirriemuir, where he wrote articles set in the town’s past for the St. James’s Gazette. Many of these were centred on a religious sect, the Auld Licht, of which his grandfather had been a member, and these articles came to earn him attention as an emerging writer. He continued to write them after moving to London, and a collection of them were published as Auld Licht Idylls (1888). This volume then became the first in a series of three works centred around the fictional town of Thrums: based on Kirriemuir. A Window in Thrums (1889), the second work, also consisted of articles previously published, but the third text was a novel entitled The Little Minister (1891). This novel was a welcome success for Barrie after the failure of his first, Better Dead (1888), which was self-published.

Around this time, while also working as a journalist, Barrie began writing plays. The first, Richard Savage (1891), he wrote with H.B Marriott Watson. It ran only once, but his next play Ibsen’s Ghost; or, Toole Up-to-Date (1891) was better received. He then met his future wife, actress Mary Ansell, while developing his play Walker, London (1892). They were married in 1894 but later divorced in 1909. Barrie became a very accomplished and prolific writer who went on to write many plays, short stories, novels, including a biography of his mother, and even two motion picture scripts. Barrie’s character of Peter Pan, however, first appeared in the novel The Little White Bird (1902), as the seven-day-old adventurer of Kensington Gardens. Those chapters featuring Peter Pan were later published in an illustrated volume named Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906). After The Little White Bird, he next appeared in Barrie’s play Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow up. The play premiered in 1904 but was not published until 1928, and, by then, he had written Peter and Wendy (1911). The text is commonly now known as Peter Pan, and it is undoubtedly Barrie’s most famous and enduring work. The character of Peter Pan was created to amuse the elder Llewelyn Davies boys, who were children of Barrie’s friends, when Peter, the middle child, was a baby. Barrie liked to tell them that their infant brother could, in fact, fly. He later adopted all five boys after the passing of their parents.

Barrie died in 1937, and he willed the rights to the novel Peter and Wendy, and the play, to the Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children.

Sources:

Brownson, Siobhan Craft, "J. M. Barrie (9 May 1860–19 June 1937)", in William F. Naufftus, ed., British Short-Fiction Writers, 1880–1914: The Romantic Tradition, 156.1 (1995): 14–24. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 156. Gale Literature: Dictionary of Literary Biography;

Rudolph, Valerie C., "James M. Barrie (9 May 1860–19 June 1937)", in Stanley Weintraub, ed., Modern British Dramatists, 1900–1945, 10:1 (1982): 32–45. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 10. Gale Literature: Dictionary of Literary Biography;

White, Donna R., "J. M. Barrie (9 May 1860–19 June 1937)", in Laura M. Zaidman, ed., British Children's Writers, 1880–1914, 141:1: (1994): 23–39. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 141. Gale Literature: Dictionary of Literary Biography,

Bio prepared by Michelle Wyatt, University of New England, michellewyatt5@gmail.com

Francis Donkin Bedford

, 1864 - 1954

(Illustrator)

Francis Donkin Bedford was born in London as the sixth child of Edwin Bedford, a solicitor. He attended Westminster School, then studied architecture at the South Kensington Schools and enrolled at the Royal Academy of Arts to become a painter and illustrator. During his Grand Tour in 1885–1891 he visited France, Spain, Tangier in Northern Morocco and Italy. His sketches from this tour are held in Victoria and Albert Museum's RIBA Drawings Collection. Although he exhibited his paintings at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition and various galleries, he is always identified with book illustration in the late Victorian and Edwardian period (see: here, here, here and here, accessed: January 13, 2022). He produced illustrations for over 50 books, as well as texts published in periodicals. Among the books he illustrated were novels by Charles Dickens, Charlotte Brontë, W. M. Thackeray and the most famous – Peter and Wendy by J. M. Barrie.

Source:

Mallalieu, Huon Lancelot, The Dictionary of British Watercolour Artists up to 1920, vol. 1, Woolbridge: Antique Collectors' Club, 1976, 36.

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Adaptations

Peter and Wendy has been reimagined very many times over in different forms of media. The adaptations range from faithful renderings to loose associations, but most works are easily recognisable by the recasting of Barrie’s characters. The adaptations linked below are some of the most notable from various media.

Peter Pan musical (1950),

Peter Pan film (1953),

Peter Pan musical (1976),

Peter Pan video game,

Hook film (1991),

Peter Pan BBC radio drama,

The Peter Pan Syndrome – Men Who Have Never Grown Up book by Dan Kiley, Avon Books, 1983,

Peter Pan in Scarlet book by Geraldine McCaughrean, Oxford University Press, 2006,

Tinker Bell film (2008),

J. M. Barrie's Peter Pan graphic novel by Stephen White, BC Books, 2015,

Peter Darling book by Austin Chant, Less Than Three Press, 2017,

Peter Pan & Wendy film (all accessed: January 13, 2022).

Translation

J.M. Barrie’s Peter and Wendy has been translated into all major world languages, and it is now widely available as an eBook on many different platforms. It is also available as an Audiobook, an eAudiobook, and there have been several editions released in Braille.

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

The character of Peter Pan appears in a cluster of J.M. Barrie’s texts. Appearing firstly in The Little White Bird (1902), he then makes his stage debut in Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up (1904). Next was Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906) before Peter and Wendy (1911). The script for Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up was then published in 1928.

Below are links to the Open Library where early edition copies of The Little White Bird and Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens can be viewed.

The Little White Bird (Accessed September 15, 2021).

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (Accessed September 15, 2021).

Summary

Peter Pan meets the Darling children, Wendy, John and Michael, when he flies into their nursery through the window one evening to retrieve his lost shadow. Mr. and Mrs. Darling are out at a nearby party, and the children’s nursemaid, a Newfoundland dog named Nana, has been dismissed from the house to a post in the backyard. The Darling children are enchanted by the mercurial Peter and by the fairy named Tinker Bell, and Peter entreats them to join him at his home in the Neverland. Captivated by the promise of a place with pirates and mermaids, and of lost boys eager for stories, the children readily agree, so Peter blows fairy dust on them to give them the power of flight. After flying around the nursery, they all soar out through the window and into the night towards Neverland. They travel past many moons, losing a sure sense of time, and, as they approach the island, the children immediately recognise it and begin to point out motifs from each other’s dreams.

The children soon learn that Neverland is not only home to Peter and the lost boys, pirates and mermaids, but also redskins (a crude reference to Native American tribes) and wild beasts. Peter tells the children of his nemesis Captain Hook, and the pirates fire the Long Tom (a cannon) skyward at them. They are unharmed, but the jealous Tinker Bell then convinces the lost boys to shoot Wendy out of the sky with their bows and arrows. Wendy is barely injured, so the boys build her a house and declare her their mother. Together, the lost boys live underground with tree trunks as entry points, and Peter soon fits the newcomers for their very own trees. Wendy does the laundry, sews and cooks for them, and tells them stories before tucking them into bed each night. She also regularly quizzes her brothers to help keep the memories of their parents alive. They have many adventures in Neverland, culminating in one where the pirates attack the camp and carry the children off to their pirate ship. They are instead rescued by Peter, who defeats Hook once and for all, leaving him to the crocodile, before himself taking command of the pirate ship.

Wendy, John and Michael fly home to their sad and despairing parents where Mr. Darling has resigned himself to life in Nana’s kennel until the return of his children. Mrs. Darling at first struggles to recognise that her children are indeed home, but the house is soon overjoyed by their arrival. The family adopts the lost boys, but Peter Pan refuses to be adopted, as it means he will one day have to grow into a man with responsibilities. He returns to Neverland, with Tinker Bell, after first securing an offer from Mrs. Darling for Wendy to return each year for spring cleaning. He only remembers to collect Wendy twice by the time she is grown, and his third visit finds her a mother with a child of her own. Her daughter Jane is then whisked away to Neverland for the spring task, and, when Jane grows up, Peter then claims her daughter, Margaret, as his mother in turn.

Analysis

Peter Pan is evidently an extension of Pan, yet there are no overt references to the horned and goat-footed god in the novel. The character, however, was first introduced riding atop a goat in The Little White Bird, and he also rode a goat and played on pipes in his early stage appearances. In Peter and Wendy his Pan-like qualities are somewhat more subtle. Just as the original Pan was known as god of the wild and untamed places, so Peter Pan lords over the relatively wild and untamed realm of childhood. Peter Pan excites the imagination, and he inspires moments of disorientation and panic, a word directly attributed to Pan, as he whisks the Darling children off to Neverland. Peter Pan is also a liminal character, existing between two worlds, just as Pan is an image of both the human and the animal.

The novel is representative of the early Edwardian revival of classical myth that functions to unsettle Victorian social mores, and it is certainly the most subversive of those children’s works featuring manifestations of Pan. While Pan appears in Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in The Willows (1908), and as Dickon in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden (1911), J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan is imbued with all the mercurial qualities of Pan’s father Hermes. He is quick, cunning and entertaining, and he escorts Wendy between London and the Neverland each spring in a reversal of the Persephone myth (where she was assisted by Hermes). As noted by Maria Tatar in the introduction to the Centennial Edition of Peter Pan, “[h]e is not simply Pan but also Adonis and Narcissus — all those mythic figures, renowned for their beauty, who refuse to grow up, mature, and develop emotional attachments” (1i–1ii). Indeed, by the invocation of these other classical figures, Pan retains his potency, but his predatory sexuality is reduced to a glib boyish charm.

In fact, the name Pan in Greek means “all”, and Barrie seems to be toying with several classical myths in Peter and Wendy. The myths of Icarus, Dionysus and Diana are also alluded to, and Neverland’s mermaids are reminiscent of the Sirens of classical mythology. Thus, readers then and now engage playfully with the classics in Peter and Wendy without necessarily knowing that they are.

Further Reading

Blackford, Holly, “Lost Girls, Underworld Queens in J.M. Barrie’s Peter and Wendy (1911) and Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847)” in The Myth of Persephone in Girls’ Fantasy Literature, London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2011, 111–133 (accessed: September 15, 2021). ProQuest EBook Central.

Blackford, Holly, "Childhood and Greek Love: Dorian Gray and Peter Pan", Children's Literature Association Quarterly 38:2 (2013): 177–198.

Jerzak, Katarzyna, “The Aftermath of Myth through the Lens of Walter Benjamin: Hermes in J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens and Astrid Lindgren’s Karlson on The Roof” in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Our Mythical Childhood…the Classics and Literature for Children and Young Adults, Brill, 2016, 44–54.

Kavey, Allison B., and Lester D. Friedman, eds., Second Star to the Right: Peter Pan in the Popular Imagination, Rutgers University Press, 2009 (accessed: September 15, 2021).

Perrot, Jean, “Pan and Puer Aeternus: Aestheticism and the Spirit of the Age”, Poetics Today 13.1 (1992): 155–167 (accessed: September 15, 2021.

Stirling, Kirsten, Peter Pan's Shadows in the Literary Imagination, London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2011 (accessed: September 15, 2021), ProQuest Ebook Central.

Valentova, Eva, “The Betwixt-and-Between: Peter Pan as a Trickster Figure”, The Journal of Popular Culture 51 (2018): 735–753 (accessed: September 15, 2021).

Addenda

The text Peter and Wendy was later named Peter Pan, and this title is the one most recognised in the contemporary cultural imagination.