Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Hanna Łochocka, "Legenda o Merkurym”, Świerszczyk 25 (1978): 387–389.

ISBN

Genre

Adaptation of classical texts*

Adaptations

Legends

Myths

Target Audience

Children (the magazine is aimed at 5-9 years old)

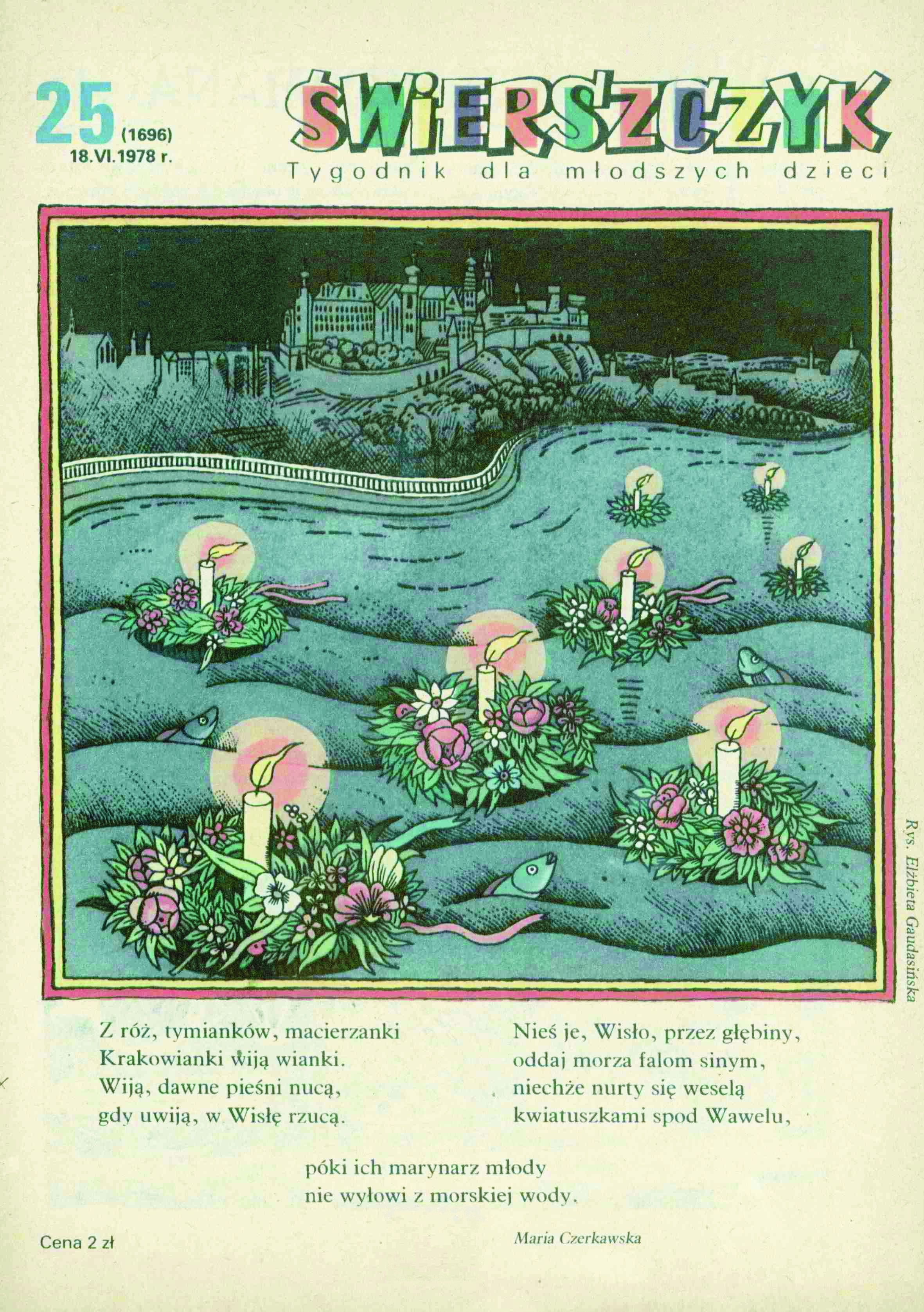

Cover

Courtesy of the publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Paweł Siechowicz, University of Warsaw, pawelsiechowicz@student.uw.edu.pl

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Photograph courtesy of Maciej Jakubowski, the Author’s Nephew, retrieved from Lech Kadlec’s website http://lechkadlec.2ap.pl/autorzy/lochocka_hanna.htm (accessed: February 22, 2013).

Hanna Łochocka

, 1913 - 1995

(Author)

Poet and prose writer, author of song lyrics and radio plays for children, translator. Educated in Warsaw as an economist and historian, she worked as an editor of economic and historic magazines; she also translated some historical works into Polish (e.g., Édouard Perroy, Roger Doucet, André Latreille, Histoire de la France pour tous les Français. Tome premier: Des origins à 1774, 1950, as Historia Francji: Od początku dziejów do roku 1774, 1969). She began her literary career as a part-time activity in 1947, when her poems were published in children magazines: Świerszczyk [The Little Cricket], Płomyczek [The Little Flame], and later Miś [The Teddy Bear]. While she also wrote poetry for adult readers and published in Poezja [The Poetry], Świat [The World], and Stolica [The Capital], her popularity stems from what she wrote for children (circa 40 books). Sparrow Elemelek – the bird-character of her three books: O wróbelku Elemelku [About Sparrow Elemelek], 1955; Wróbelek Elemelek i jego przyjaciele [Sparrow Elemelek and His Friends], 1962, and Psoty i kłopoty Wróbelka Elemelka [Sparrow Elemelek’s Pranks and Troubles], 1972 – is one of the best known characters of Polish children’s literature.

Sources:

Kadlec, Lech, Hanna Łochocka, http://lechkadlec.2ap.pl/autorzy/lochocka_ hanna.htm (accessed 22.02.2013).

"Łochocka Hanna", in: Krystyna Kuliczkowska; Barbara Tylicka, eds., Nowy słownik literatury dla dzieci i młodzieży, Warszawa: Wiedza Powszechna, 1979, pp. 334–335.

Bio prepared by: Paweł Siechowicz, University of Warsaw, pawelsiechowicz@student.uw.edu.pl

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

This story explains Mercury’s role within the Roman pantheon and the genesis of his attribute: caduceus. In the presented version of the myth, Mercury stole Jupiter’s lightning and was accused of flashing out Venus’ doves, stealing Mars’ sword, Neptune’s trident, and Apollo’s arrows and quiver. The stolen lightning exploded under Mercury’s tunic when Jupiter got angry at him. Realizing the impropriety of his acts, Mercury decides to change and become the guardian of traders and travellers. He uses the extinguished lightning to save Venus from two snakes crawling towards her. The lightning, decorated with snakes and doves’ feathers, becomes his walking stick – caduceus. In the meantime, the reader also learns that Mercury constructed the first lyre adding a string to a turtle’s shell; he then gave it to Apollo.

Analysis

Funnily and lightly, the story presents the character of the Roman god Mercury, the origin of the caduceus, relevant for its meaning in culture, and at the same time emphasizes a moral lesson: rules are to be respected and misbehaving does not pay.

Mercury is here like a trouble-making child unaware of the consequences of his reckless conduct. What he did for fun turned out to bother others and be harmful to Mercury himself. The story is written with humour, vibrant dialogues present a family scene, where various family members complain in unison to the pater familias about his child’s mischief and pranks. At first, the witty delinquent tries to distract the father to avoid talking to him about tiresome issues, such as small thefts, and then defending himself against multiple accusations – any contemporary child caught misbehaving would do the same. The Olympic gods complain one after another, and the boy sinks deeper into shame, precisely as he should. For the young readers’ better understanding of the situation, the author goes a step further and shows that all the pranks upset adult gods and that there is real risk involved in “borrowing” what belongs to adults without their permission. The moral lesson is reinforced by the image of the remorseful delinquent who promises to change and use his powers for a good purpose – as a messenger of gods and people, a guardian of trade, merchants and travellers. The author explains that Mercury kept his promise and was worshipped and respected by Romans for his frequent assistance.

The transformation of an ancient prankster into a good boy who is responsible, caring, and wise is not the only lesson the young reader can acquire. Even if the story is short, it is also enjoyable, and there is plenty of information that children can effortlessly assimilate. Jupiter, Mars, Neptune, Apollo, and Venus are provided with a basic description and can be easily remembered. Caduceus, part of the boy’s transformation, becomes a familiar symbol. The children learn that it was relevant and widely used in Rome, signifying peace and concord, prudence and diligence; all the qualities needed in trade. Under Mercury’s protection, it played an important role in political, legal, military, and religious issues ( e.g., insignia of heralds). Unfortunately, Maria Sołtyk’s drawings only show Mercury with the stolen lightning and not with the caduceus, the famous staff with two entwined snakes and two wings at the top, which could have helped the children remember this new difficult term.

Further Reading

F. F., “The Press in the Satellite Countries”, The World Today 9.6 (1953): 256–265. (accessed: March 7, 2022).

Kadlec, Lech, Hanna Łochocka, http://lechkadlec.2ap.pl/autorzy/lochocka_ hanna.htm (accessed: February 22, 2013).

"Łochocka Hanna", in: Krystyna Kuliczkowska and Barbara Tylicka, eds., Nowy słownik literatury dla dzieci i młodzieży, Warszawa: Wiedza Powszechna, 1979, 334–335.

Piecuch, Ewelina, “W gąszczu dziecięcych potrzeb – znaczenie edukacyjne tekstów kultury popularnej na podstawie czasopisma dla dzieci pod tytułem “Świerszczyk”, Kultura – Społeczeństwo – Edukacja 2/16 (2019): 117–133.

Addenda

Illustrations: Maria Sołtyk.