Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Elsie Finnimore Buckely and Frank C. Papé, Children of the Dawn: Old Tales of Greece. London: Wells Gardner, Darton & Co., Ltd.; New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, [1908], 390 pp.

ISBN

Available Onllne

Children of the Dawn: Old Tales of Greece London edition at the Internet Archive (accessed: September 16, 2022).

Children of the Dawn: Old Tales of Greece New York edition at the Internet Archive (accessed: September 16, 2022).

Children of the Dawn: Old Tales of Greece at Project Gutenberg (accessed: September 16, 2022).

Genre

Anthology of myths*

Fiction

Target Audience

Children

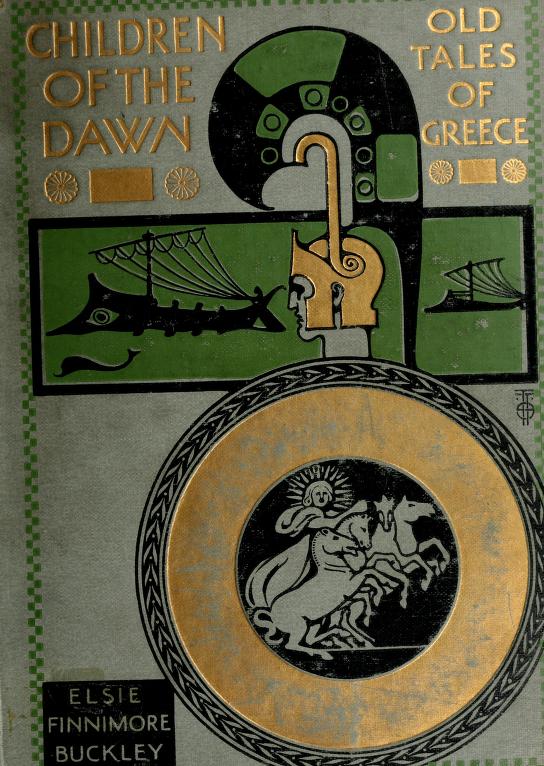

Cover

Retrieved from the Internet Archive (accessed: September 16, 2022). Not in copyright.

Author of the Entry:

Robin Diver, University of Birmingham, robin.diver@hotmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaoundé 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

Elsie Finnimore Buckley

, 1882 - 1959

(Author)

Elsie Finnimore Buckley (b. August 1882, Calcutta) was a British children’s author and translator. She wrote the children’s anthology of myth Children of the Dawn in 1909, and published several translations, including The Third Republic by Raymond Recouly (1928). The daughter of a civil engineer, Buckley won a gold medal in the Société Nationale des Professeurs de Français en Angleterre's French language and literature competition when she was sixteen. She studied at Girton College, Cambridge. She was married to writer Anthony Ludovici from 1920, and lived with him in South London.

Sources:

Wikipedia (accessed: September 16, 2022).

Bio prepared by Robin Diver, University of Birmingham, RSD253@student.bham.ac.uk

Frank C. Papé

, 1878 - 1972

(Illustrator)

Frank C. Papé was a British artist and illustrator known for illustrating books of children’s folk and fairy tales. He studied at The Slade School of Fine Art. He was married to illustrator Alice Stringer.

Papé began his career by illustrating Emile Clement’s 1902 Naughty Eric and Other Stories from Giant, Witch, and Fairyland, followed by The Toils and Travels of Odysseus (1908), Elsie Finnimore Buckley’s 1908 anthology of Greek myths Children of the Dawn, The Pilgrim’s Progress (1910), Fifty-Two Stories of Classic Heroes (1910) and Half a Hundred Hero Tales of Ulysses and the Men of Old (1911), as well as illustrations for the Psalms.

In 1915, he enlisted for the army. He resumed his illustration career in the 1920s and enjoyed success in the US as well as Britain. In 1930, he illustrated an edition of Suetonius. By the late 1950s he had significant issues with his eyesight. His last known work is for a 1968 Robinson Crusoe reprint.

Sources:

Wikipedia (accessed 16th April 2021).

Bio prepared by Robin Diver, University of Birmingham, robin.diver@hotmail.com

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

Summary

This is a detailed, extensive retelling of eleven key Greek myths with significant attention often given to character development, and details of the character’s education and early life. Scenery, landscape and geography are also described at length. The featured stories are:

The Riddle of the Sphinx

Eros and Psyche

Hero and Leander

The Sacrifice of Alcestis

The Hunting of the Calydonian Boar

The Curse of Echo

The Sculptor and the Image

The Divine Musician

The Flight of Arethusa

The Winning of Atalanta

Paris and Œnone

Analysis

The first paragraph of the Oedipus story tells us ancient Greece is famous for "mighty deeds of mighty men ... which still kindle the hearts of men, and stir them up to be heroes too, and fight life's battle bravely." (p. 1)*. This statement places Buckley’s anthology in the tradition of Kingsley’s 1856 children’s anthology The Heroes, promoting Greece as exemplary for its warrior spirit in a way that is supposed to still resonate to the anthology’s contemporary audience. After the First World War, this particular tradition in reception would become highly controversial and criticised, seen to have fuelled warmongering spirit and led to glorification of unnecessary death in the battlefield (Murnaghan and Roberts 2018).

The beginning of the Oedipus story has been somewhat altered to reflect the early twentieth century ideal of 'mother love' and the importance of the biological nuclear family over other forms. Here, Jocasta is asked to kill the baby Oedipus, but she tells him that she will not because those who have ordered her (including seemingly Oedipus' father) "know not a mother's love." Although she still abandons him, she also states "I would rather die than lose thee". It is the slave whom Jocasta entrusts Oedipus to the care of who pierces his ankles without her knowledge; Jocasta is therefore blameless of physically harming her own child in any way. After this, however, "the gods (...) shed (...) a grace" on Oedipus that makes the slave love him. In this version, therefore, compassion from a non-blood related adult requires divine powers to kindle, but a mother could never kill her biological child (although a biological father may). This ignores the frequent reality of infanticide in ancient Greece that makes the generality of Jocastas statement about a mother's love rather inaccurate (p. 1).

On the other hand, Oedipus is shown to be close to his adoptive mother Merope, to the point that when he is warned he will kill his father, he laments in particular that this would "bring (...) sorrow to my mother's heart." (p. 6). In this version, Oedipus does not marry Jocasta. Jocasta simply vanishes from the story after Oedipus' birth, and Oedipus has another unnamed wife who speaks some of Jocasta’s lines in Sophocles. The Oedipus retelling is also negative about the people of the city, using ancient oligarchic rhetoric to criticize their fickleness and complain that they do not think enough of Oedipus and worry only "how the plague might be stayed" (p. 11).

There appears to be some discomfort in this anthology with the idea of female monsters. Oedipus initially addresses the sphinx "fair and softly" because she is beautiful, but when she answers savagely, he "saw that by her cruelty and lust she had killed the woman's soul within her, and the soul of a beast had taken its place." (p. 7).

The Psyche retelling, meanwhile, emphasises Victorian complementary ideals of men and women in marriage and the misery of singlehood for women. There is particular emphasis on Psyche's unhappiness at the start when she is not married. When her sisters persuade her that her husband means her harm, they do not warn her he may eat her or do other violence as in other versions, but that he will abandon her and leave her "all ashamed and deserted" (p. 22). This threat of being left alone by a husband is enough to persuade Psyche to betray Eros. In this version, the sisters are particularly cruel and Eros eventually punishes them by coming to them, pretending to love them instead of Psyche and then tricking them to their deaths. The Psyche retelling could perhaps therefore be said to be more black and white than other versions of the story, a feature that is fairly consistent across the other anthology retellings in this volume.

A Macmillan reader (a reviewer who works for a publisher), when considering this text, wrote that "The plain truth is that this is not woman's work, and a woman has neither the knowledge nor the literary tact necessary for it." (Tuchman and Fortin 1989, p. 87.) It is not clear if this reader was opposed to the concept of women writing children’s anthologies of myth generally, or if something about Buckley’s tone compared with other female myth anthology writers of the time particularly offended the reviewer. Possibly, this might have been that the writing style is not as playful and always obviously for children as in similar contemporary texts, or that more detail and background is given for each story than in other rival anthologies, making it perhaps seem to be more "intellectual".

* Page numbers in analysis refer to Classic Books of All Time edition (CreateSpace Independent Publishing, no date).

Further Reading

Murnaghan, Sheila and Deborah H. Roberts, Childhood and the Classics: Britain and America, 1850-1965, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Tuchman, G. and N. Fortin, Edging Women Out: Victorian Novelists, Publishers and Social Change, London: Routledge, 1989.