Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

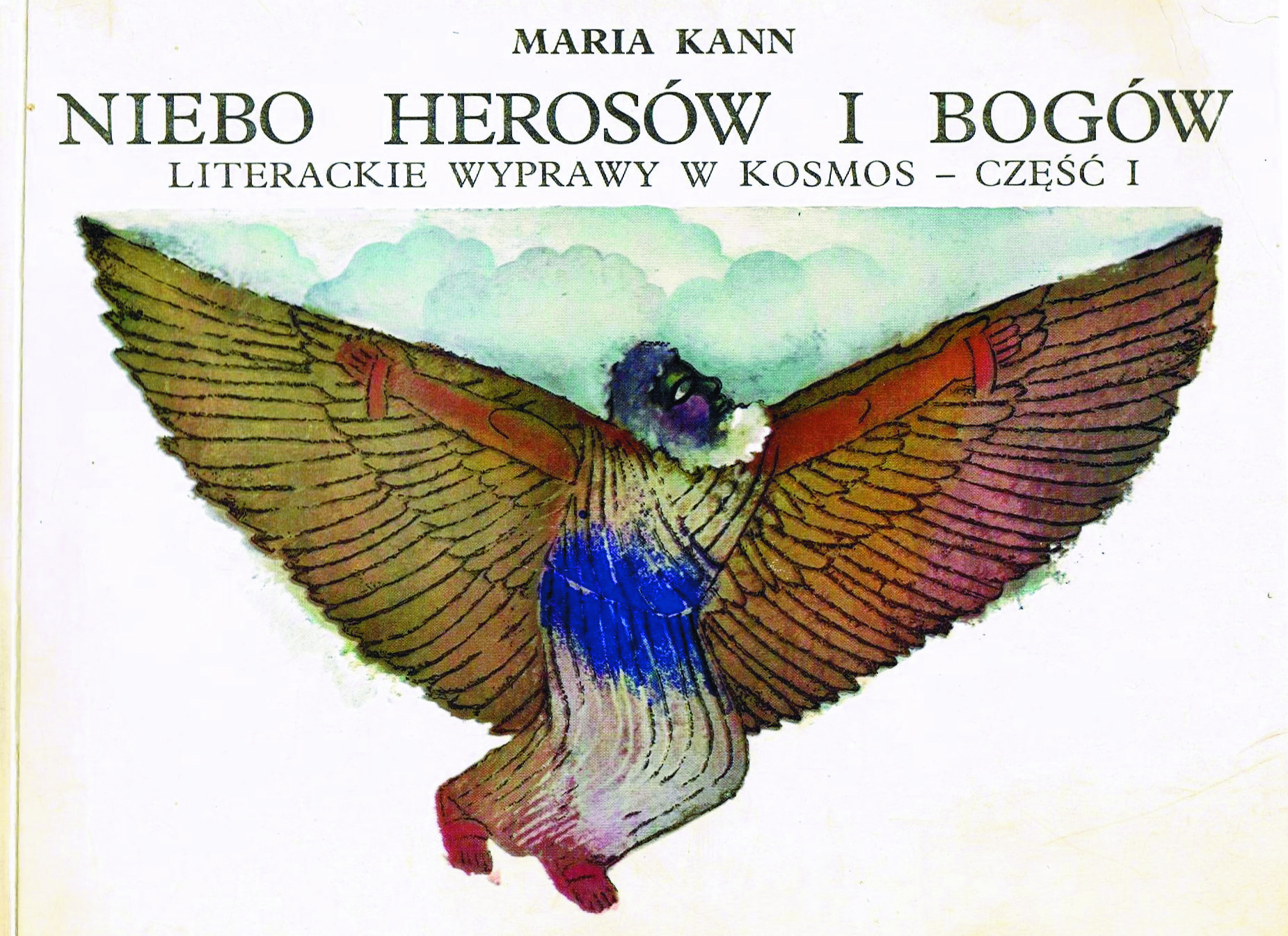

Maria Kann, Niebo herosów i bogów. Literackie wyprawy w kosmos — Część I, ill. Antoni Boratyński. Warszawa: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, 1975, 84 pp.

Genre

Action and adventure fiction

Adaptations

Anthology of myths*

Fiction

Short stories

Target Audience

Children

Cover

The publisher of the text closed down in 2004 leaving no known successors, and we were unable to determine if there are any copyright holders. Including the cover in our database meets all fair use requirements, still, we invite the users to share with us any information they may have about copyrights to the posted materials.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Karolina Zieleniewska, Univeristy of Warsaw, k.zieleniewska@hotmail.com

Analysis: Hanna Paulouskaya, University of Warsaw, hannapa@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Antoni Boratyński

, 1930 - 2015

(Illustrator)

Antoni Boratyński was an illustrator and graphic artist. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw (1950–1951) and Budapest (1951–1956). He worked with many publishing houses and received many Polish and international awards. In 1978, he was included in the international H. Ch. Andersen Honours List.

Source:

“Antoni Boratyński” at Zachęta Art Gallery website (accessed: February 17, 2023).

Bio prepared by Hanna Paulouskaya, University of Warsaw, hannapa@al.uw.edu.pl

Photograph from Zawadzka, Anna and Zofia Zawadzka, Z pamiętników i wspomnień harcerek Warszawy 1939–1945, Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1983, retrieved from the Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Maria Kann

, 1906 - 1995

(Author)

A writer, author of children’s books, scouting activist and WW2 Resistance fighter. After the war she was arrested and jailed for her involvement in Polish independence organizations banned by the Communist regime (she was a member of Armia Krajowa [Home Army]). In 1932 she began writing essays for periodicals connected to scouting. From 1946 to 1952 she worked also as an editor at the publishing house “Czytelnik.” Author of many novels, such as: Niebo herosów i bogów. Literackie wyprawy w kosmos – Część I [Heaven of Heroes and Gods. Literary Expeditions into Space – Part I], 1947; Pilot gotów? [Ready, Pilot?], 1947; Baśń o zaklętym kaczorze [A Fairytale about an Enchanted Male Duck], 1957; Niebo nieznane [Heaven Unknown], 1964, or Granice świata [The Borders of the World], published posthumously 2000.

Source:

Zabłocka, Grażyna, "Marii Kann granice świata", Podkowiański Magazyn Kulturalny 39, (2003) (accessed: September 16, 2022).

Bio prepared by Karolina Zieleniewska, Univeristy of Warsaw, k.zieleniewska@hotmail.com

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue (accessed: June 11, 2021), Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

This story uses the oldest myths, legends and poems about the eternal human dream of flying. The author uses several ancient sources, such as Sumerian mythology, the Greek myth about Daedalus and Icarus, the Chinese poetry of Qu Yuan, legends about Alexander the Great, and the works of Lucian of Samosata, to tell a story about flying written as a personal narration. The book also contains an appendix with some information about the ancient sources used in the stories.

Analysis

The action takes place, i.a., during the Graeco-Roman Classical Antiquity (also in ancient China and Sumer). It covers five myths, legends and poems connected to flying (first of all, the famous myth about Daedalus and Icarus) as well as a description of historical figures (e.g., Alexander the Great, Lucian of Samosata).

The myths and stories are presented in sufficient detail. The text includes fictional dialogues and descriptions of the historical context as well as quotations or retellings of ancient texts. Each chapter starts with a historical introduction printed in italics to distinguish it from the myth itself and usually includes a short postscript with historical information, especially concerning later periods. The text provides additional data in several footnotes. However, there are no detailed references to the ancient sources. After five chapters, there is a supplement entitled “For those who want to know more” [Dla tych, którzy chcą wiedzieć więcej] with short literary and historical comments on the included stories. The book is illustrated with many black and white sketches drawn in the style of ancient pictures and woodcuts. Each chapter has at least one elaborate picture in full colour (the fifth chapter has two) showing travels in the sky.

The myth of Daedalus is discussed in the second chapter, “Master Daedalus’ Wings” [Skrzydła mistrza Dedala]. The story starts in Athens and describes Daedalus’ rivalry with Talos, his nephew, and his death, which is not a necessary element in mythologies for children. Then, we learn about Daedalus’s escape to Crete. He regrets causing his nephew Talos’ death and claims it was an accident. Cursed by his sister, who was Talos’ mother, Daedalus is afraid for his son’s life.

A detailed retelling of the story of Icarus emphasizes the boy’s dreams of flying (pp. 28–29). The text repeats the warning of Daedalus to Icarus to obey his instructions using the examples of Phaethon and Bellerophon (p. 28). The death of Icarus was his fault – he was not careful and did not listen to his concerned father. Although the text does not contain a straightforward moral lesson, it communicates a clear message addressed to young readers.

Another, more realistic version of the myth is presented, in which the father and son escape by boat with “white wings of sails”, and Icarus dies falling overboard (pp. 31–32). The reason for his death is his carelessness. The story serves to provide the etymology of the name Icarian Sea.

The postscript contains information on archaeological excavations of Crete in the 19th century. A note on the linear scripts A and B and on the Mycenaean culture is also included.

The fourth chapter, called “Lord of the Earth, Sea and Air” [Władca Ziemi, Morza i Powietrza], presents legends about Alexander the Great. It starts with his childhood and education by Aristotle. The heliocentric and geocentric (Ptolemaic) concepts of the universe are shortly described: the boy Alexander prefers the idea of the Sun being the center of the universe, but Aristotle argues for the Ptolemaic vision as more in tune with contemporary empirical knowledge. This passage may encourage young readers to express their opinion and defend it even in front of the greatest authorities.

Later on, Kann briefly presents Alexander’s conquests. The legend about Alexander carried into the air on gryphons is included (pp. 55–56): on his way to the oracle of the god Ammon to learn his fate, Alexander and his army are almost lost in the desert. They find their way with the help of gryphons they meet there. Alexander uses the creatures to carry him up in the sky. However, “the gods did not allow” Alexander to fly too high to prevent a mortal from ignoring his limitations. Retelling this legend, the author emphasizes that a man must be humble and that it is impossible to equal gods – the ancient concept of hubris corresponds to the Christian concept of humility.

The fifth and the last chapter, entitled “A Teaser Hosted by the Gods” [Kpiarz w gościnie u bogów], presents the life and works of Lucian of Samosata. A True Story (Ἀληθῆ διηγήματα; Verae Historiae) is shortly described (pp. 62, 65). However, the emphasis is on Lucian’s dialogue Icaromenippus. Menippus of Gadara was a famous Cynic philosopher and satirist whose works, although lost, were described by authors such as Lucian or Varro. Menippean satire is a genre named after him. In Icaromenippus, the philosopher attaches the wings of a vulture and an eagle to his arms and flies to Olympus to discover the true nature of the universe. On his way, he stops on the Moon and listens to Selene’s (i.e., the Moon’s) complaints about philosophers bothering her with their studies. Selene asked Menippus to pass the request to Zeus to punish the philosophers. Kann repeats Lucian’s satirical criticism against contemporary philosophy; there is no specific message to modern young readers. It is a summary of the philosophical, satirical dialogue and a tribute to the first science-fiction writer in the history of literature: “And here, for the first time in literature, the satellite of Earth became a stopover for human beings on their way to the more distant regions of the Cosmos.” [I oto ziemski satelita po raz pierwszy w literaturze stał się przystankiem dla człowieka w drodze do odleglejszych rejonów Kosmosu.] (p. 75).

Further Reading

Zabłocka, Grażyna, "Marii Kann granice świata", Podkowiański Magazyn Kulturalny 39, 2003 (accessed: September 16, 2022).