Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Stanisław Srokowski, Bajki Ezopa, ill. Marta Działocha. Wrocław: Izba Wydawnicza „Światowit”, 2003, 112 pp.

Based on: Maria Ganaciu, Georgia Mammi and Stanisław Srokowski, Bajki Ezopa, ill. Marta Działocha, Warszawa: Oficyna Wydawnicza Volumen Mirosława Łątkowska & Adam Borowski, [1991], 54 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Adaptation of classical texts*

Fables

Short stories

Target Audience

Children

Cover

Courtesy of the publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Sylwia Chmielewska, University of Warsaw, syl.chm@gmail.com

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

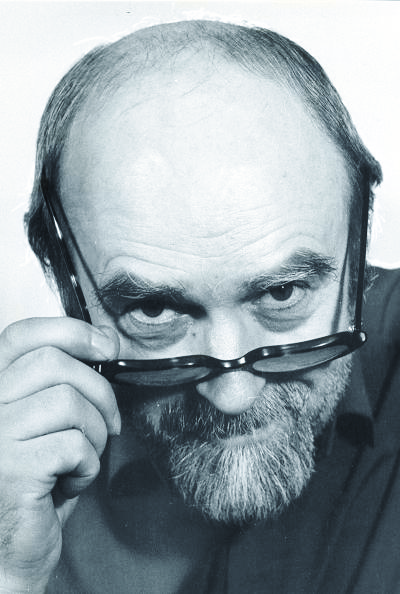

Courtesy of the Author

Stanisław Srokowski

, b. 1936

(Author)

Stanisław Srokowski is a poet, novelist, playwright, literary critic, translator and essayist. Born near Tarnopol (in eastern Poland before WW2, now Ukraine). He started as a high school teacher, and then he branched out into journalism. He also joined “Solidarność” [Solidarity] – the first non-Communist trade union in Communist Poland.

Author of about 50 books, including several novels and short stories, and books for children. He won numerous literary prizes and awards, e.g., Australian International Prize POLCUL and among Polish awards, Stanisław Piętak Literary Award, Józef Mackiewicz Literary Award, and others. His prose and poetry were translated into many languages, including English, Japanese, and several European languages. His literary work is strongly connected with the culture of eastern pre-war Poland, as well as with ancient literature and culture.

Source:

The Author's Website (accessed: November 2, 2021);

"Srokowski Stanisław", in Jadwiga Czachowska and Alicja Szałagan, eds., Współcześni polscy pisarze i badacze literatury. Słownik biobibliograficzny, vol 7: R– Sta, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 2001, 407–410.

Bio prepared by Sylwia Chmielewska, University of Warsaw, sylwia.chmielewska@student.uw.edu.pl, syl.chm@gmail.com

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

A collection of Aesopian fables featuring traditional and “non-traditional” animals as main characters; the fables are written in prose. Every fable tells a tale in a very expressive manner, in a colourful language; all of the fables end with a moral. The collection includes the following fables:

Żółw i zając [The Tortoise and the Hare]. The famous story of two unequally matched rivals. The hare, confident of winning, interrupts the race several times, and finally falls asleep. In the meantime, the slow but determined tortoise makes it to the finish line. The moral: one should not underestimate those who seem to be weaker, and one should always work hard, even if success seems a foregone conclusion.

Chory jeleń [The Ailing Deer]. One day a deer got very sick. The other animals pretended to be concerned, but when the deer fell asleep, they ate all the grass on the poor animal’s grazing ground. The story ends with a scene of the squirrel bringing food to the deer, and saying: “sometimes silly friends bring more loss than profit.”

Lis i winogrona [The Fox and the Grapes]. A very hungry fox stole a goose from a nearby village. The next day the proud fox boasted about his deed, but when he tried to steal another goose, he was nearly caught. Still hungry he tried to eat some grapes, but they were growing too high. At the end, a magpie made fun of the fox, who said that he did not want sour grapes. The moral: one who lacks success, always blames the circumstances.

Dwa koguty [The Two Roosters], based on the fable known as The Fighting Roosters and the Eagle. The rosters argue about which of them crows louder, whose neck, wings, feathers, etc. are more beautiful; finally they start a fight. The other birds cheer them on until one wins. When the winner gets on the roof of the cottage and starts boasting of his prowess, a large eagle grabs him. The moral: nothing good comes of boasting; pride goes before disaster.

Orzeł i żuk [The Eagle and the Beetle], based on the fable known as The Dung Beetle and the Eagle. A large eagle is spotted by animals. All flee instantly, but a little hare remains in the field, unaware of danger. The eagle grabs the hare, who calls for help his friend the beetle. The insect tries to persuade the bird to let the hare go, but the eagle refuses to relinquish his prey and flies away holding the poor animal in his talons. The revenge of the beetle is terrible: every time the eagle lays eggs, the beetle breaks them. The moral: one should not despise or underestimate the weak.

Mysz i żaba [The Mouse and the Frog]. A mouse invites her friend the frog to dinner at the pantry, where she lives. The frog wanting to reciprocate, invites the mouse to her pond. Because the mouse cannot swim, the frog ties their legs together with a rope and they both jump into the pond to find food. The frog does not realize that the mouse begins to drown. At the end they are both caught and eaten by a kite. The moral: bad advice, even from friends, always leads to a bad outcome.

Lew i komar [The Lion and the Mosquito]. Forest animals had organized sports competitions. A tiger wins the sprint race, a panther is first in hurdle race, and a kangaroo wins the long jump. Then the fighting competition began, with a lion, a bear, an ox, an elephant and a wolf as qualified participants. After several fights, the lion is declared winner, and is acclaimed King of Wisdom, Strength and Courage. The lion proud of his success challenges anybody who believes himself stronger. A mosquito accepts the challenge to great amusement of all onlookers. The insect wins by stinging the lion and while boasting of his victory, he falls into a spider-web. The moral: those who overthrow the great, often fall victim to the small.

Orzeł i lis [The Eagle and the Fox]. An eagle and a fox form a friendship, after one helped the other to avoid dangerous hunters. They decide to live in proximity and help each other to bring food to their offspring. Time passed, and when the eagle saw the fox and his cubs always having enough to eat, while he himself could not feed his family properly, he grabbed all the cubs and brought them to his eaglets. The betrayed and desperate fox tried in vain to reach the eagle’s nest. One day the eagle brought to his nest a piece of meat, without noticing a piece of a burning cinder attached to it. The little flightless eaglets frightened by the flame fell down from the nest and were eaten by the fox. The moral: those who betray their friends should not count on impunity, even if their victims themselves could not retaliate.

Mrówka i żuk [The Ant and the Beetle], based on the fable known as The Ant and the Dung Beetle. A lazy beetle plays the drums while a small ant works hard storing food for the winter. The beetle keeps making jokes about the ant, but when the winter finally comes, the drum player has neither home nor food to keep him alive. Finally the beetle asks the ant for help, but she refuses to give him anything, saying that if he had thought of his future earlier, he would not need to ask anyone for help now. The moral: one should think of the future even in times of happiness and joy, in order not to risk problems when luck turns.

Lew, wilk i lis [The Lion, the Wolf and the Fox]. One day the old lion king fell ill. A wolf came to the king with a gift and accused the fox of being disrespectful to the lion. The fox heard the words of the wolf and started to explain to the angry king that he had travelled far to find a cure for the king’s sickness. He said: “You must slay a wolf and wrap yourself up in his skin.” The lion did as the fox advised and rewarded the fox saying that the wolf clearly did not wish him well. The moral: beware of crafty and sly characters, because they can fool you and pretend to be helpful.

Jak kawka została królową [How the Jackdaw Became a Queen], based on the fable known as The Vain Jackdaw or The Lion and Jackdaw. The lion, king of the animals, announced a beauty contest. All the birds gathered near the spring and started to prepare for that event. After the birds left for the contest, the jackdaw took the feathers they had dropped, and fastened them about her own body. Then, she attended the contest along with other birds. The king was enchanted by her appearance and just when he announced that she will be the beauty queen, the other birds recognized her and stripped her of the stolen feathers. The moral of the story is that one should not pretend to be someone else and that “all that glitters is not gold.”

The book ends with a short biography of Aesop related to the history of Aesopian fables.

Analysis

According to the afterword added by the publisher, this book belongs to the European tradition of works based on ancient motifs well known from Aesop’s fables, seen as a core to be adapted, transformed, and reshaped. Aesop’s fables are very short, like the fable genre in general, and are addressed to adults; the author selects some of them and reshapes them entirely.

With his grandson Piotruś in mind, Srokowski adapted several Aesopian motifs and created interesting brief bedtime stories that can be read by children or by their parents. Following the Aesopian pattern, anthropomorphic animal characters represent human virtues and vices. From each story, a moral lesson comes, often due to the protagonist’s reflection, as if the Socratic method was used. However, the stories are not only meant to teach but also to amuse and entertain the reader. For this reason, the author transformed each selected fable in a manner that speaks well to children – full of descriptions including even small details, adjusted to the age of readers and their cultural and geographical situation. The animals also have a voice in lively dialogues using a colloquial but still elegant, current, easily understood language.

The first fable, The Tortoise and the Hare [Żółw i zając], can be used as a good example of how the stories are built. The leading motif here, based on Aesop’s fable Χελώνη καὶ λαγωός, is the race in which the slow but persistent contestant – the Tortoise – is underestimated by the fast, overconfident Hare, who, despising his rival, neglects the race, takes a nap, and loses. First and foremost, Aesop presents the situation in just a few verses, and only two characters are mentioned. Srokowski develops the story into a fairy tale. The scene of the race is full of animals behaving like humans. The race is described as part of a big contest with prizes and numerous spectators, a kind of animal game. There are various species in the audience. Even though the main discipline is the hare race, the spectators here are big and small Polish forest animals, such as foxes, martens, wolves, badgers, wildcats, roe deer, and bears. The motif of a lion as the king of animals, even though there are no lions in the Polish woods, creates a fairy-tale ambiance and adds a universal aspect to the tale. After the last hare race, the tortoise challenges the winner to a duel. Then, the race starts again, a magpie hangs a start ribbon, squirrels serve as judges, and the finish line is placed at the opposite side of the village. This sets the story in the Polish woodland reality; the image is reinforced when the hare stops running to listen to a choir of frogs and a concert by a grasshopper or to play cards with other hares before he takes his nap. All the animal characters are part of a diverse community, a mythical animal world where anything is possible. The reader observes a perfect match between the original Aesopian motif, its La Fontaine adaptation or the Polish ones (such as, for instance, Ludwik Kern’s), as well as the fairy-tale ambiance present in the magic forest.

The moral lesson is not given to the reader ex cathedra. It is important that the hare realizes, with a slight hint of regret, that it is wrong to underestimate those who seem weaker. The hare is a graceful loser who learned his lesson and decided never to mock, despise or ignore anyone.

Further Reading

Hall, Edith, “Our Fabled Childhood: Reflections on the Unsuitability of Aesop to Children”, in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Our Mythical Childhood... The Classics and Literature for Children and Young Adults, Brill, 2016, 171–82.

[The Author’s Website] (accessed: September 22, 2022).

"Srokowski Stanisław", in Jadwiga Czachowska, Alicja Szałagan, eds., Współcześni polscy pisarze i badacze literatury. Słownik biobibliograficzny, vol 7: R– Sta, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pegagogiczne, 2001, 407–410.