Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

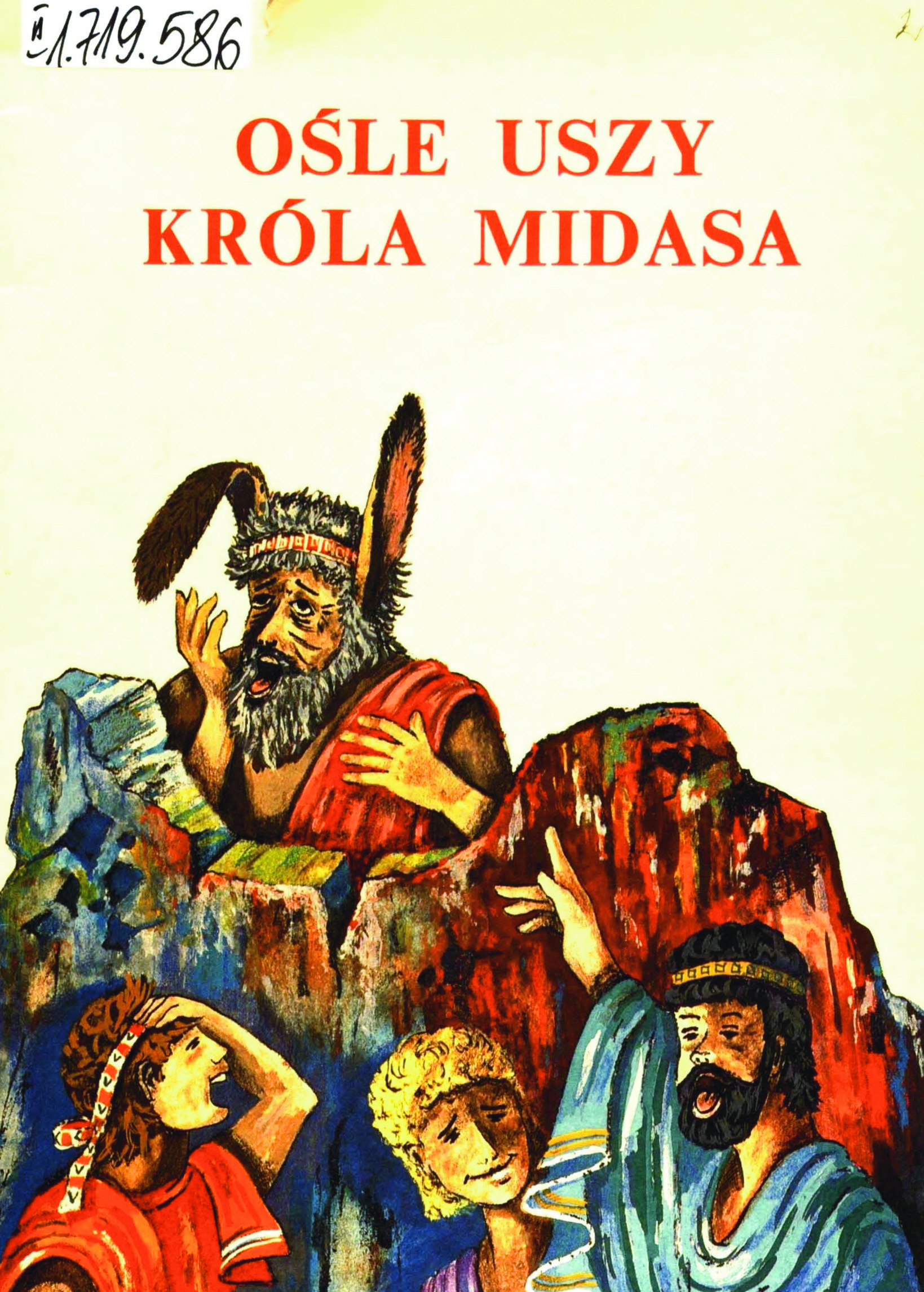

Stanisław Srokowki, Ośle uszy króla Midasa, ill. Marta Działocha. Wrocław: Izba Wydawnicza „Światowit”, 1992, 24 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Adaptation of classical texts*

Myths

Short stories

Target Audience

Children

Cover

Courtesy of the publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Sylwia Chmielewska, University of Warsaw, syl.chm@gmail.com

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Courtesy of the Author

Stanisław Srokowski

, b. 1936

(Author)

Stanisław Srokowski is a poet, novelist, playwright, literary critic, translator and essayist. Born near Tarnopol (in eastern Poland before WW2, now Ukraine). He started as a high school teacher, and then he branched out into journalism. He also joined “Solidarność” [Solidarity] – the first non-Communist trade union in Communist Poland.

Author of about 50 books, including several novels and short stories, and books for children. He won numerous literary prizes and awards, e.g., Australian International Prize POLCUL and among Polish awards, Stanisław Piętak Literary Award, Józef Mackiewicz Literary Award, and others. His prose and poetry were translated into many languages, including English, Japanese, and several European languages. His literary work is strongly connected with the culture of eastern pre-war Poland, as well as with ancient literature and culture.

Source:

The Author's Website (accessed: November 2, 2021);

"Srokowski Stanisław", in Jadwiga Czachowska and Alicja Szałagan, eds., Współcześni polscy pisarze i badacze literatury. Słownik biobibliograficzny, vol 7: R– Sta, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 2001, 407–410.

Bio prepared by Sylwia Chmielewska, University of Warsaw, sylwia.chmielewska@student.uw.edu.pl, syl.chm@gmail.com

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

The story begins with a detailed description of Dionysus’ entourage – thiasos (θίασος): one member of the thiasos, the old Silenus, drank too much wine and fell asleep in the garden near Midas’ palace. He was soon discovered by the king’s servants and invited by Midas to dinner. Silenus entertains the king with two tales (about two cities, one full of happiness, the other consumed by evil, and about two trees, one which gives people joy, and the other causing death). Later, the king takes Silenus back to Dionysus, who was worried his friend had gotten lost. Overjoyed at Silenus’ return, the god promises to grant Midas one wish: the king asks to be able to turn everything he touches into gold. According to the book, Midas was close to losing his mind after turning the garden, the palace, and the royal herds into gold. He realises that his gift is, in fact, a curse when he tries to embrace his son, Sangaris, and transforms him into a golden statue. Distraught and desperate, Midas returns to Dionysus and begs him to take his “gift” away. The god tells him to wash his hands and body in the river Pactolus. The river washes away the Golden Touch, and all that it had transformed into gold returns to life.

The second, shorter episode shows Midas at the mountain Tmolus, where he witnesses an argument between Apollo and Pan. Apollo plays the lyre, while Pan plays the flute. The king praises Pan’s music above Apollo’s and is punished by the offended god with a pair of donkey’s ears. The king tries to hide them under a headdress, but his barber, of course, knows the secret. He cannot keep it to himself and wants to share the secret without betraying the King. He goes out into the meadow, digs a hole in the ground and shouts the story into it. Unfortunately, the reeds hear it all and begin whispering: “King Midas has donkey’s ears.” The story ends with a moral expressed by king Midas himself: foolishness brought him to this pitiful end.

Analysis

Srokowski retells the myth of King Midas in a lively, amusing and illuminating manner. The narrative is built around the didactic aim of showing the reader how to appreciate and enjoy life. Srokowski uses the Socratic method: readers are supposed to draw conclusions and find answers on their own. Happiness can be achieved with what one already has, even if prima facie “more” seems “better”.

Dionysus’ thiasos is composed of joyous creatures surrounding the smiling god. They are happy to be together merry-making on earth instead of feasting on Olympus with other gods. Their evident enjoyment of life is somewhat reckless but attractive; they are described as “party animals” and revellers. Silenus does not mind being the target of their harmless practical jokes.

Silenus’ stories provide Midas with another opportunity to grasp the sense of being content with the status quo. Sober and after a nutritious breakfast, Silenus becomes calm, deliberate and wise. Out of gratitude for Midas, he tells him two stories suggesting how difficult it is for people to be satisfied, that “more” does not equal “better” and that the land of eternal happiness – Utopia – does not exist. Midas did not understand the point of the tales; despite being already extremely wealthy, he still desired more possessions. He was clearly begging for another lesson. The granting of his wish resulted in losing everything that had real value.

Srokowski also reuses Hawthorne’s motif of Midas’ child who loves roses; instead of his daughter Marygold, we meet his son, Sangaris. From the child’s perspective, the value of roses is their natural beauty, colour, smell and appearance, which attracts bees. Midas does not understand and ignores the beauty of nature admired by his child; he is blinded by overwhelming greed, which only makes him value gold. He again misses the opportunity to appreciate the importance of what he already has in his life. Although Hawthorne’s motif is not ancient, it appeals to the child reader and makes the retelling more attractive to the target audience.

As Midas obsessively turns everything into gold, despite his son’s disapproval, he faces the final lesson when he is left alone in the middle of a stilled, golden desert with no signs of life. The didactic goal reaches its fulfilment when the unfortunate wish is reversed, and Midas thanks Dionysus in words of gratitude and happiness. This time he is free from what he now considers a curse, the lust for “cold treasures” (p. 20).

Srokowski presents Midas as an imperfect human being. Even when warned again by the wise Silenus against pride and lack of respect for the gods’ will and the beauty they created, Midas transgresses again by questioning the result of the contest between Apollo and Pan. While he is entitled to his opinion, his error comes from hubris. Midas speaks in a bossy and contemptuous manner, even lacking respect for Apollo. The king places himself above the god and is punished for his lack of discernment in music and respect for Apollo. The author succeeds in using Midas’ vices and shortcomings as the basis for a moral lesson addressed to the child reader and, at the same time, provides an amusing story worth reading and re-reading as a bedtime story.

Further Reading

[The Author’s Website] (accessed: September 22, 2022).

"Srokowski Stanisław", in Jadwiga Czachowska, Alicja Szałagan, eds., Współcześni polscy pisarze i badacze literatury. Słownik biobibliograficzny, vol 7: R– Sta, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pegagogiczne, 2001, 407–410.