Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Guadalupe Garcia McCall, Summer of the Mariposas, New York: Tu Books, 2012, 352 pp.

ISBN

Official Website

Summer of the Mariposas (accessed: July 21, 2025)

Awards

2013 — Westchester Young Adult Fiction Award.

Genre

Action and adventure fiction

Fantasy fiction

Novels

Target Audience

Young adults

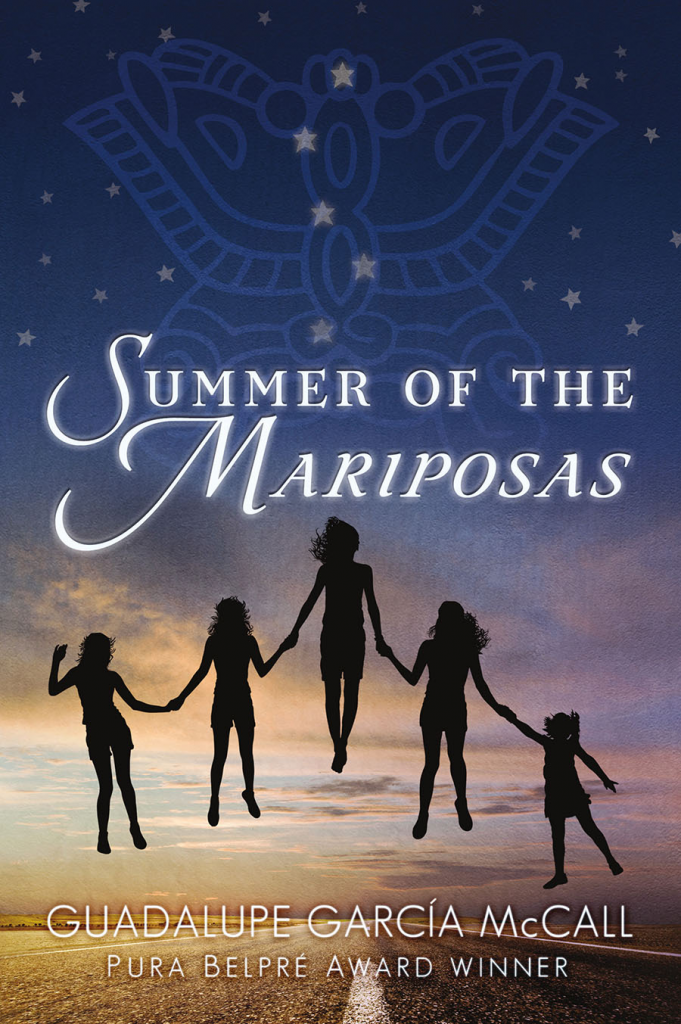

Cover

Summer of the Mariposas. Text copyright © 2012 by Guadalupe García McCall. Permission arranged with Tu Books, an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS Inc., New York, NY 10016. All rights reserved.

Author of the Entry:

Alex Guerin, Victoria University of Wellington, alexbguerin@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Babette Puetz, Victoria University of Wellington, babette.puetz@vuw.ac.nz

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Guadalupe Garcia McCall at the 2018 Texas Book Festival, Austin, Texas, US. © 2018 Larry D. Moore. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Guadalupe Garcia McCall (Author)

Guadalupe Garcia McCall is a writer of young adult novels, children’s poems and some adult short stories. She was born in Piedras Negras, Coahuila, Mexico, and raised in Eagle Pass, a small border town in Texas that serves as the setting for the beginning of her fantasy novel Summer of the Mariposas.

Garcia McCall taught English at primary and high school level in San Antonio, Texas before moving to George Fox University, Oregon to teach undergraduate courses in literature, women’s studies, and creative writing. After publishing her first novel, Under the Mesquite (2011), she won the Pura Belpré Medal and the Tomás Rivera Book Award. Her second novel, Summer of the Mariposas (2012), a retelling of the Odyssey that traverses Texas and Mexico, won the Westchester Young Adult Fiction Award.

Garcia McCall is now a full-time writer and part-time educator, living in South Texas. Fluent in English and Spanish, she has given speeches at many schools, universities and conferences, promoting diverse literature and books inspired by an author’s own experiences.

Sources:

The author's website (accessed: July 21, 2025).

Profile at Poets and Writers (accessed: July 21, 2025).

en.wikipedia.org (accessed: July 21, 2025).

Bio prepared by Alex Guerin, Victoria University of Wellington, alexbguerin@gmail.com

Translation

Spanish: El verano de las mariposas, trans. David Bowles, Tu Books, 2018.

Summary

Summer of the Mariposas follows five young Chicana sisters, the ‘cinco hermanitas’, through Texas and Mexico on a magical journey that draws from Greek and Mexican mythology. It is narrated by the oldest sister, Odilia. The story begins at Eagle Pass, a small town in Texas near the Mexican border where the girls are being raised by their single mother. Swimming in the local river, the girls find a dead body floating in the water. All the girls except for Odilia elect to return the man’s body to his family so that he can receive a proper burial. Eventually Odilia is forced to join the other sisters and, borrowing their absent father’s car, they embark on a journey into Mexico to return the corpse to his family.

Odilia meets La Llorona, a misunderstood figure from Mexican folklore who gifts her a magical earring and provides guidance throughout the story. La Llorona encourages the sisters to stick together and learn kindness and purity of heart.

Using the magical earring, Odilia sneaks her sisters and the dead man across the border and to the house of his family. Arriving at the house, the girls realise that they have stumbled upon his daughter’s ‘quinceanera’ (a party that celebrates a girl’s 15th birthday, marking her transition to womanhood). Not wanting to spoil the mood, they discuss what to do until the dead man’s son finds them and they are forced to explain the reason for their trip. The girls find out that the man was not the long lost husband and father they had imagined, but a man who had abandoned his family many years before, like their own father had done. After being offered food and shelter, the ‘cinco hermanitas’ leave the man with his family and continue to the house of their Abuelita, their grandmother on their father’s side, who they have not seen in years.

The girls are beset by a number of obstacles on their journey, including an evil ‘bruja’ (witch) who attempts to imprison them with food that makes them forget their true selves, and a ‘nagual’ (warlock) in the shape of a donkey, who tries to cook them to release himself from his curse. After escaping the powerful nagual with the help of an Aztec goddess, they are set upon by ‘lechuzas’ (witch owls), nightmarish beasts that attack them and prey upon their specific fears and insecurities. Finally, they must escape from a ‘Chupacabra’ (demon) who befriends and then attacks them. The youngest sister, Pita, is bitten and her wound becomes infected by the Chupacabra’s poison.

Hurt and exhausted, the cinco hermanitas stumble to the house of their Abuelita, who receives them with open arms. After a stay with their grandmother, the sisters recover their energy and are driven to the US border. Having forgotten their papers, they must seek the divine aid of ‘la Virgen de Guadalupe’, the Mexican embodiment of Mary, the Holy Mother who is associated with Tonantzin, the Great Mother from Aztec mythology. After praying to la Virgen de Guadalupe they receive a miracle, being transported on a canoe across a mystical lake back to their hometown. The girls are reunited with their mother but they find that their father has returned to the family home with La Sirena, the woman he has been having an affair with, and her two daughters. The father causes a rift in the family that heightens tensions but brings the girls closer to their mother. In the end their mother moves on and finds love again and the ‘cinco hermanitas’ have a happy ending.

Analysis

Garcia McCall’s Summer of the Mariposas weaves elements of the Odyssey and other aspects of Greek mythology with elements from Aztec mythology and other Mexican folklore to create a modern story centred around five Chicana sisters, who embark on a journey to learn about their cultural heritage, the importance of sticking together and a mother’s guidance. Whereas Homer’s Odyssey glances back to an heroic age propped up by exceptional warriors striving for eternal fame, Summer of the Mariposas deals with contemporary issues, but delves into the cultural and mythical past of its Mexican setting. Rewriting the Odyssey and certain Mexican myths from a feminist perspective, Garcia McCall rejects the patriarchal undertones inherent in the original stories, while promoting Mexico’s rich cultural heritage. The references to Homer and other aspects of Greek mythology provide a structure for Garcia McCall’s story and the litany of classical references appear as cultural touchstones for an audience perhaps less acquainted with Mexican legends.

Each chapter in the novel is assigned a card from the popular Mexican folklore-inspired game ‘lotería’ that foreshadows aspects of the story. Odilia tells us that the cards were originally called out by their father and the rhymes on the cards symbolise a traditional patriarchal mode of storytelling. Such games condition children into accepting and reproducing traditional social norms. Abandoned by their father, the original head of the household, the sisters must resist these folktale interpretations and create their own story.

Early in the narrative, we are introduced to La Llorona, an evil woman from Mexican folklore who murdered her own children. The legendary figure of La Llorona evolved from the historical story of Malitzin, an Aztec slave girl given to Hernán Cortés, the Spanish conqueror. Malitzin became his translator and mistress. According to the stories, Cortés left to return to the Spanish court and there he was engaged to a Spanish woman. After spurning Malitzin, Cortés returned to Mexico to retrieve the children he had with her. Out of spite, Malitzin drowns her children and she is cursed to wander along the river searching for them for eternity. In the traditional interpretation Malitzin, conflated with La Llorona, is presented as a mad woman resembling the vicious Medea from Greek mythology. Rewriting this story from a feminist perspective, Garcia McCall recasts her as a loving mother that cannot rest until she finds her children who, during an argument with her husband Hernán, became afraid and ran into the water. La Llorona occupies the helper goddess role in the story, as Athena does in the Odyssey. She provides guidance and magical assistance to Odilia, the eldest of the ‘cinco hermanitas’. At the end of the novel Odilia gifts La Llorona magical flowers given to her by the Virgen de Guadalupe. Upon receiving the flowers, La Llorona is transformed into an Aztec princess and she is reunited with her children among the stars. In Greek mythology figures such as Heracles and Ganymede are rewarded for their deeds by being immortalised as constellations. La Llorona’s eventual metamorphosis grants her peace in recognition of her suffering and the help that she gave the ‘cinco hermanitas’. The rewriting of La Llorona’s character challenges patriarchal norms which have portrayed mothers, and women in general, as crazy. As Garcia McCall writes her novel from a feminist perspective, La Llorona is finally allowed to tell her side of the story. As a guiding figure, La Llorona instils in Odilia the need to challenge certain narratives that she has been told, such as mothers being responsible for any harm that befalls their child. By reinterpreting a folktale that has been passed down to her, Odilia and her sisters reject certain patriarchal narratives and are able to repair their own relationship with their mother.

Odilia, the narrator and eldest sister, has several parallels with her similar sounding counterpart from the Odyssey. Homer attaches the epithet ‘polytropos’ to Odysseus, literally meaning ‘of many turns’ but encompassing Odysseus’ extensive wanderings and sufferings as well as his wily nature and talent for disguise. The term ‘polytropos’ can also be applied to the eternally resourceful Odilia, who uses her talents to protect her younger sisters. In an attempt to discourage the sisters from embarking on a dangerous and foolhardy journey, Odilia disguises herself as their Mama who is really out at work. Although the ruse is successful, Odilia is dragged into the girls’ Odyssey as she cannot abandon them. With the aid of La Llorona’s magical earring, Odilia persuades the border control officer to let them pass with a corpse in the back seat, and she convinces the family of the dead man to offer them hospitality. The family is at first wary, but they warm to Odilia and her sisters, mirroring Odysseus’ own experience with the Phaeacians. Odilia’s craftiness gets her through dangerous situations, though she relies somewhat on La Llorona’s assistance, as Odysseus relies on Athena’s aid.

La Llorona helps the sisters again as they fall into the trap of the evil ‘bruja’ Cecilia, who evokes comparisons to the enchanting witch Circe. The sweet-voiced Cecilia leads the ‘cinco hermanitas’ to her beautiful house in the woods. Starving, thirsty and exhausted, the girls are offered endless treats and encouraged to rest. With the help of La Llorona, Odilia discovers that Cecilia is slipping a powerful drug into her baking, that induces sleep and apathy in the girls, reminiscent of the lotus fruits in the Odyssey. As Hermes offers Odysseus moly, a magical herb to protect him from the spells of Circe, Odilia is given a drink by La Llorona to counteract Cecilia’s magic. After coming to her senses, she is able to free the other sisters and they toss the rest of Cecilia’s baking to the pigs. Giving their own food to the pigs, they release themselves from Cecilia’s thrall and avoid joining the apathetic creatures as Odysseus’ crew did under Circe’s spell. As they refuse Cecilia’s hospitality, Juanita, the second eldest sister, taunts the witch. In a moment that recalls Odysseus’ taunting of Polyphemus and his subsequent punishment by Poseidon, Cecilia curses the sisters and their journey to Abuelita’s house is thrown off course by various monstrous creatures.

There are numerous aspects of the novel which have parallels in classical mythology. We are introduced to a dog named Serberús, that waves its head in frantic excitement so that it seems to have three heads. Though not integral to the plot, this moment is a playful reference to the fearsome guard dog of Hades. Later on the girls travel to the house of the seer Teresita to discover the path to their Abuelita’s place. Teresita has cataracts and can barely see, closely resembling the blind prophet Tiresias, who appears in the Odyssey to tell Odysseus how he will fare on his voyage home. Teresita warns the girls that “you have angered the witch [Cecilia] and you will be punished for your transgressions”. The girls must escape from the cave of a shapeshifting nagual that wants to eat them, reminiscent of Odysseus and his crew’s escape from the lair of the Cyclops. They fend off the attacks of the lechuzas, vicious owls that taunt the girls with the misdeeds they have committed, such as abandoning their mother with no explanation. The ‘lechuzas’ resemble the Furies from Greek mythology that haunt those who have committed divine crimes such as matricide.

Summer of the Mariposas deviates from the thematic structure of the Odyssey as the girls question their choice to abandon their mother and must seek forgiveness towards the end of the story. Odysseus, despite not being faithful by modern standards, is portrayed as a mostly righteous hero while his neglected wife Penelope is regarded as the archetype of a good Greek woman. Odysseus’ disappearance, in which he misses most of his son’s life, is emulated by Papá, the girls’ father who abandons them with no explanation. Having fallen for ‘La Sirena’, a terrible woman who brings him to ruin, Papá attempts to return to his family with his new partner but he is rejected by the ‘cinco hermanitas’ and their Mamá, who they have reconciled with. Advising Odilia early in the novel, La Llorona emphasised the importance of the journey for “reuniting” the ‘cinco hermanitas’ with each other as well as with their Mamá and long lost Abuelita. La Llorona’s message rejects the premise that the estranged Papá is the missing link that will bring them together, as a perfect retelling of the Odyssey would suggest.

Garcia McCall recognises the importance of fiction in shaping the experiences of children and young adults. Written from the perspective of a Chicana girl whose story draws from the author’s own lived experience, Summer of the Mariposas speaks to young Chicana girls who have little representation in mainstream media. By reinterpreting the male-centric story of the Odyssey as well as tales from Mexican folklore that support existing power structures, the novel functions as a counter-narrative that gives voice to the oppressed and the forgotten. In bringing old folktales to life, Garcia McCall also emphasises the importance of ancient knowledge that is transmitted orally down the generations. The novel shines a light on cultural relics of Mexico’s pre-Colombian past, such as the vibrant city of Tenochtitlan, the powerful goddess Tonantzin and the healing properties of indigenous plants. By looking to the past, Garcia McCall provides a blueprint for recovering cultural identity and challenging traditional power structures.

Further Reading

Cummins, Amy, and Myra Infante-Sheridan, "Establishing a Chicana feminist bildungsroman for young adults", New Review of Children's Literature and Librarianship 24.1 (2018): 18–39.

Furumoto, Rosa, "Future Teachers and Families Explore Humanization Through Chicana/o/Latina/o Children's Literature", Counterpoints 321 (2008): 79–95.

Herrera, Cristina, "Cinco Hermanitas: Myth and Sisterhood in Guadalupe García McCall's Summer of the Mariposas", Children's Literature 44.1 (2016): 96–114.

Addenda

Edition used: Guadalupe Garcia McCall, Summer of the Mariposas, New York: Tu Books, 2012, 303 pp. (e-book).