Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

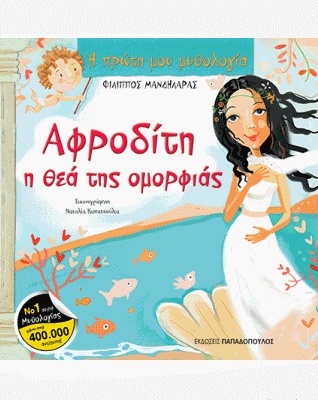

Filippos Mandilaras, Αφροδίτη η θεά της ομορφιάς [Afrodítī ī theá tīs omorfiás]. My First Mythology [Η Πρώτη μου Μυθολογία (Ī prṓtī mou Mythología)] (Series), Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2017, 36 pp.

ISBN

Available Onllne

Demo of 7 pages available at epbooks.gr (accessed: October 13, 2021).

Genre

Illustrated works

Mythological fiction

Myths

Picture books

Target Audience

Children (Reader: 4+)

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Dorota Mackenzie, University of Warsaw, dorota.mackenzie@gmail.com

Natalia Kapatsoulia (Illustrator)

Natalia Kapatsoulia studied French Literature in Athens, and she worked as a language tutor before embarking on a career as a full-time illustrator of children’s books. Kapatsoulia has authored one picture book Η Μαμά πετάει [Mom Wants to Fly], which has been translated into Spanish Mamá quiere volar. Kapatsoulia, who now lives on the island of Kefalonia, Greece, has collaborated with Filippos Mandilaras on multiple book projects.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Profile at the epbooks.gr (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Filippos Mandilaras

, b. 1965

(Author)

Filippos Mandilaras is a prolific and well-known writer of children’s illustrated books and of young adults’ novels. Mandilaras studied French Literature in Sorbonne, Paris. His latest novel, which was published in May 2016, is entitled Υπέροχος Κόσμος [Wonderful World], and it recounts the story of teenage life in a deprived Athenian district. With his illustrated books, Mandilaras aims to encourage parents and teachers to improvise by adding words when reading stories to children. Mandilaras is interested in the anthropology of extraordinary creatures and his forthcoming work is about Modern Greek Mythologies.

Sources:

In Greek:

Profile on EP Books' website (accessed: June 27, 2018).

i-read.i-teen.gr (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Public Blog, published 15 September 2015 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Press Publica, published 28 January 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Linkedin.com, published published 6 May 2016 (accessed: February 6, 2019).

In English:

Amazon.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

On Mandoulides' website, published 7 March 2017 (accessed: June 27, 2018).

In German:

literaturfestival.com (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Summary

Mandilaras and Kapatsoulia recount Aphrodite’s life, starting with her birth from the sea in Cyprus and ending with her veneration in Greek temples and legacy for sculptors and painters.

Aphrodite emerged from the sea in a large seashell. She was beautiful and everyone fell in love with her. Zephyrus travelled with Aphrodite, first to the island of Cythera – where he spent a night with her – and afterwards to the west part of Cyprus. In Cyprus, the Hours made Aphrodite beautiful and then led her to Olympus, for the gods to decide about Aphrodite’s partner. Having chosen Hephaestus for her husband, Zeus presented her with a magical belt. When Aphrodite put the belt on, Ares, the god of war, fell madly in love with her. Hephaestus became envious, and one night he used a fishing net to trap Ares and Aphrodite. In Mandilaras’ evaluation, her beauty meant trouble for Aphrodite. In her many adventures, winged Eros was her companion.

Next, Mandilaras recounts how one of Aphrodite’s adventures was her affair with Adonis. Aphrodite put Adonis in a box, asking Persephone to keep him in the underworld. Adonis grew up to be handsome, and Persephone refused to give Adonis back. Zeus’s decision was for Adonis to spend four months with Persephone, four with Aphrodite, and four with whomever he liked. Aphrodite wore her magical belt to win Adonis over. Ares, filled with envy, turned into a wild boar and killed Adonis. Flowers grew from Adonis’ blood and from Aphrodite’s tears.

At the end of the book, we read that people in ancient Greece worshipped Aphrodite, who was always young and charming. For artists, she was the ideal woman. Two additional sections follow, offering background information. One section is about the Judgement of Paris. The other section covers Aphrodite’s reception in ancient and modern art. There are sketch drawings of Aphrodite in a black-figured vase scene, of the Aphrodite of Melos, of Aphrodite in a seashell in Sandro Botticelli’s painting, and of Kapatsoulia’s rendering of Aphrodite in this book.

Analysis

This book celebrates Aphrodite’s beauty, and how multiple gods and mortals – Zephyrus, Hephaestus, Ares, Hermes, Dionysus, Poseidon, and anonymous herdsman, Adonis, as well as sculptors and painters – loved the goddess. Falling in love, however, does not always bring happiness, as the gods can become extremely jealous and angry. Aphrodite’s love affairs are described as adventurous. Aphrodite is devastated about Adonis’ death, and she is shown crying amidst red roses, anemones, and other flowers. Perhaps there is a hint here what flower Adonis will become. There are warnings that being a beautiful woman does not guarantee a happy life.

Modern visual registers are abundant in the book’s illustrations. Aphrodite is represented as a young bride, wearing a long white dress that resembles a wedding gown. The gown is fitted tightly to Aphrodite’s body, showing off her slim and sexy figure. A nude Aphrodite is featured only in Kapatsoulia’s sketch drawings of the Aphrodite of Melos and of Botticelli’s ‘Birth of Venus’ at the very end of the book. The Hours, the goddesses of the seasons, resemble bridesmaids, as they comb Aphrodite’s hair, apply makeup to her cheeks, paint her finger nails, polish her toenails, and remove hair from her legs with what looks like a wax strip. Depilation is very down to earth, and it reflects contemporary ideas about body hair in the western world. Zephyrus, the mythical personification of a gentle wind, mounts a cloud together with Aphrodite, and the two look like a young couple riding a motorbike. The underworld recalls a hotel’s reception area, with signs reading ‘welcome’ and ‘check-in’. Young children, therefore, are encouraged to think about contemporary life, and how Aphrodite would look and behave if she lived today. Indeed, in Kapatsoulia’s sketch drawing of Aphrodite at the end of the book, Aphrodite recalls a sexy teenager. She wears a mini skirt and a shoulderless top and she takes a selfie.

There are gender stereotypes in connecting beauty with a female persona and with men’s possessiveness. There appears to be no emphasis on Aphrodite’s representations in ancient statuary, where the goddess was associated with nudity. As Rosemary Barrow argued, correctly in my view, Aphrodite’s divine status made her body, and her sexuality, unattainable for mortals in antiquity*. In this book, the distance between gods and mortals is shortened. We read that Aphrodite was beautiful from birth at the beginning of the book. Aphrodite undergoes, nonetheless, a process of beautification by the Hours. Also, it is Zeus’ magical belt that makes Aphrodite irresistible for men. Whether innate qualities are sufficient then for Aphrodite to act as a femme fatale remains open. Rather, text and image here seem to convey a message that any girl can become even more beautiful, which I find particularly positive for children today.

Mandilaras’ language is simple, but some words are elevated and literary. These include: κόρη [maiden]; κόκκινα ρόδα [red roses]; and πριν το γέρμα [before the sunset]. Children and adults are expected to have an excellent command of the Greek language. Ares confesses his love for Aphrodite in couplets, and these could allude to the erotic poetry of Cyprus, Rhodes, and Crete of the medieval period**. It is unclear whether Mandilaras implies that there could be continuity between ancient Greek literature and traditional folksongs ***. Mandilaras’ literary words seem to be geared towards preparing children for their formal education at primary school and high school, when students learn about the Greek language, and its regional idioms, in ancient, recent, and modern times.

* See Rosemary Barrow, “The Body, Human and Divine in Greek Sculpture”, in Pierre Destrée and Penelope Murray, eds., A Companion to Ancient Aesthetics, London: John Wiley & Sons, 2015, 94–108. (accessed: July 27, 2018).

** See www.odyssey.com.cy/main/default.aspx?tabID=145&itemID=1311&mid=1076 (accessed: July 27, 2018, no longer available).

For discussion of Καταλόγια [Katalogia], see high-school textbook in Greece: Kostas Balaskas, Κείμενα Νεοελληνικής Λογοτεχνίας, Α’ Τάξη Γενικού Λυκείου, Athens: Ministry of Education, 2011, 74–75. For online version, see www.odyssey.com.cy/main/default.aspx?tabID=145&itemID=1311&mid=1076 (accessed: July 27, 2018, no longer available).

*** For the debate, see bmcr.brynmawr.edu (accessed: July 27, 2018).

Further Reading

Information about the book at epbooks.gr (accessed: July 26, 2018)

Addenda

From the series My First Mythology.