Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

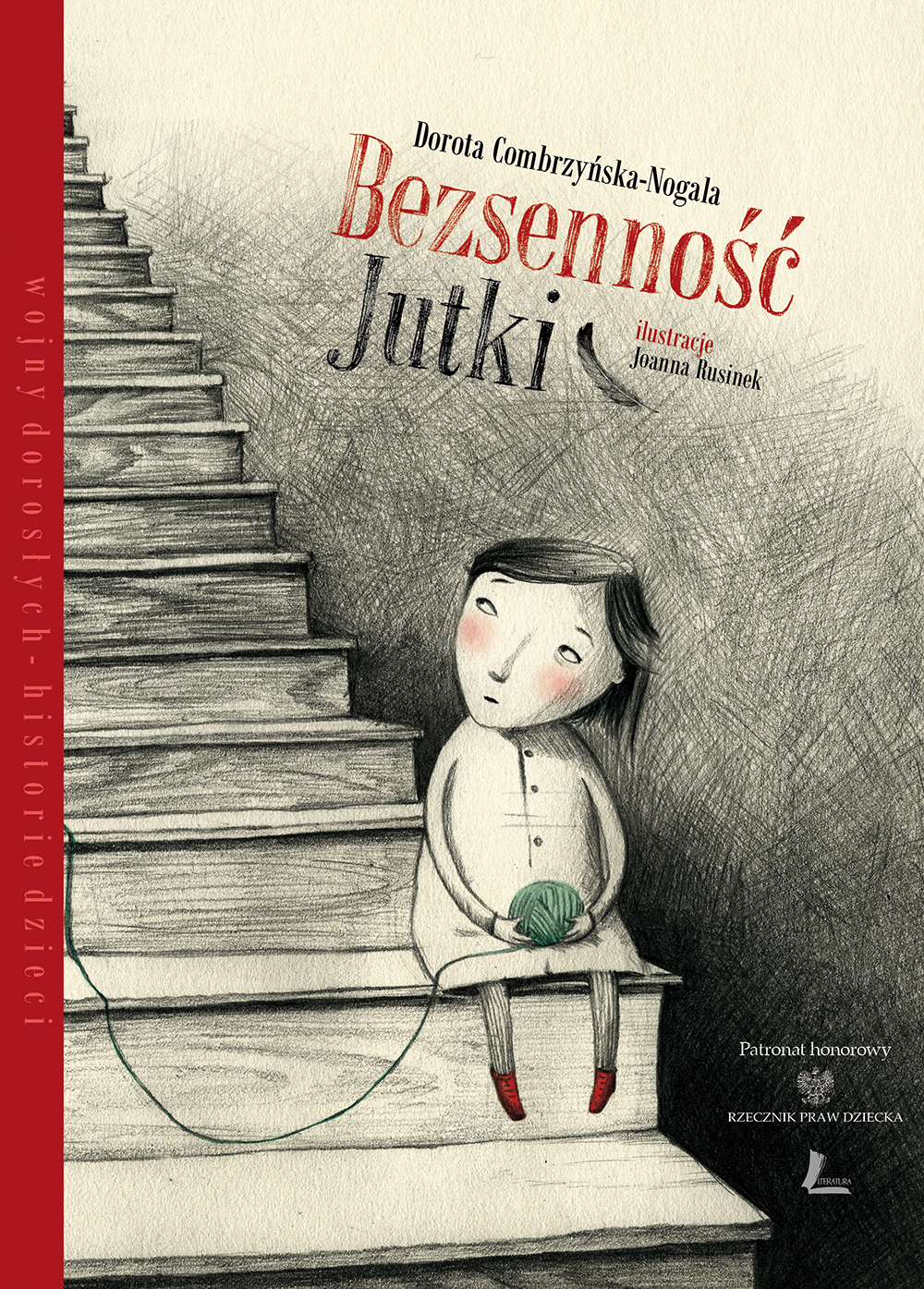

Dorota Combrzyńska-Nogala, Joanna Rusinek ill., Bezsenność Jutki. Łódź: Literatura, 2012, 79 pp.

ISBN

Awards

2013 – The 1st prize in the 1st "Child-Friendly Book" competition, organised by the Museum of Toys and Play in Kielce;

2012 – Nomination for the "Book of the Year" award by the Polish Section of IBBY.

Genre

Fiction

Historical fiction

Illustrated works

Novellas

War fiction

Target Audience

Children (According to the publisher’s website: 7+)

Cover

Courtesy of Literatura, publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Courtesy of the Author.

Dorota Combrzyńska-Nogala

, b. 1962

(Author)

A philologist, teacher of the deaf, writer. Graduated from the University of Łódź. Author of novels for adults, such as Naszyjnik z Madrytu [A Necklace from Madrid] (2007), Wytwórnia wód gazowanych [Soft Drinks Factory] (2012), and Drewniak [A Wooden House] (2012). She also completed Charlotte Brönte’s unfinished work, Ashword, published in 2015 as Chcę wszystko [I Want Everything]. Particularly devoted to writing for children and young adults. Her most popular books for the younger audience are: Piąta z kwartetu [The Fifth from a Quartet] (2008), Bezsenność Jutki [Jutka’s Insomnia] (2012), Syberyjskie przygody chmurki [Siberian Adventures of the Cloudlet] (2014), and Możesz wybrać, kogo chcesz pożreć [You May Choose Whom You Want to Devour] (2014). Her latest novel is Skutki uboczne eliksiru miłości [Side Effects of Love Potion] (2017). For her work, she received numerous prizes, such as "Władysław Reymont Award" (commemorating the Polish writer who in 1924 won the Nobel Prize in Literature) and the first prize in the "Child-Friendly Book" contest. She currently lives in Łódź.

Source:

Profile at the wyd-literatura.com.pl (accessed: July 4, 2018).

Bio prepared by Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Questionnaire

1. What attracted you to Classical Antiquity and what challenges did you face in selecting, representing, or adapting particular myths or stories?

As Bezsenność Jutki is not based on a story of an existing person (which I would have tried to present to contemporary children – and also, in many cases, to their young parents), I had to look into records, diaries, and historical studies in order to create a believable character. Among them, what impressed me the most were the words by Oskar Singer, the chronicler of the Łódź Ghetto: “The man in the Ghetto is an evil man. The evil created by such a man is greater than what could be explained by the self-preservation instinct.”

2. How does it translate to your story?

The whole modern ethics is based on the Great Commandment of Love (“Love thy neighbour as thyself”) and Singer asks a universal question: What’s left of it in extreme situations? This is why I wanted the norms and culture, something permanent in the world that collapses, represented by myths, to be present in this frightening place – the Ghetto. Jutka’s grandfather is a symbol of humanity: he raises the girl taking care of not only her physical survival. And myths are not just a device of education but, in this case, they also constitute – similarly to fairy tales – a kind of compensation literature, which makes one survive the suffering and, simply, relax him or her. The choice of myths I made was rather an intuitive than a rational one. In fact, I am not sure who made this selection: me or my character, Dawid Cwancygier. Daedalus and Icarus have wings, and the grandfather and the granddaughter from my story can imagine that they can fly too, and that they are able to fly away from the Ghetto, which – just like Crete – is kind of a closed island. Interestingly, some historians perceived the end of my story as unrealistic. I insisted that the text ends with Jutka and her aunt leaving the Ghetto – they just leave it, they are not rescued… We don’t know what could have happened later (sometimes during meetings with the audience, children imagine the characters’ future – and some of them have no illusions about the women’s fate). However, Ewa Wiatr, a historian from the University of Łódź, checked the records and – to her own surprise – it turned out that in roughly the same time two females managed to exit from the Ghetto.

3. So it was the Ghetto’s being almost completely closed that made you use the Cretan myth?

The myth came to my mind when I was reading about the "Szpera" and about people living in the Litzmannstadt Ghetto who were trying to hide. The narrowness of this claustrophobic and, as I said, closed district reminded me of the labyrinth, and therefore the figure of the Minotaur appeared naturally.

4. Referring to your story’s allusions to antiquity – do you have a background in classical education (also: Latin or Greek at school or classes at the University)?

No, I don’t have such a background, although I had classes about classical literature and I learned Latin at the University (unfortunately, with poor results). I owe the knowledge of Greek myths to the primary school.

5. Jutka, having listened to her grandfather’s stories, refer to them later in her life. What, in your opinion, did these narratives give her? And what do they give contemporary children?

The girl survived in the basement, keeping a ball of wool in her hands. I assume that the story of Theseus and Ariadne definitely help her in dealing with the situation. Contemporary children, reading and listening to myths, but also to fairy tales, become equipped with patterns of thinking and acting, with certain archetypes, and these things can support them in real life. We all use this priceless heritage, even when we are not aware of it.

6. Do you think that classical / ancient myths, history, and literature continue to resonate with young audiences?

Yes, I suppose, but it depends on the way of presenting them. For example: young people associate fantasy literature with myths, and this kind of writing is heavily read by them, and by adults too.

6. You mentioned fantasy and, earlier, fairy tales. Why did you choose to use myths instead of other kinds of fantastic narratives?

I don’t know why, but I didn’t think about fairy tales at all when creating my story. Maybe myths are something even more universal and fundamental for me? Nevertheless, cultural tales and ethical norms are not given once and for all, so they still constitute something we have to work on.

Prepared by Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Courtesy of the Author.

Joanna Rusinek

, b. 1978

(Illustrator)

A press and book illustrator, poster artist, book cover designer, creator of animated films. Graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow (Graphic Arts Department). She is particularly focused on children’s books illustrations – her work in this field includes graphics both to well-known classics (i.e. J. M. Barrie’s Peter and Wendy) and contemporary Polish texts (i.e. Jarosław Mikołajewski’s Wędrówka Nabu [Nabu’s Journey]). She illustrated a couple of books published in Literatura publishing house’s series Wojny Dorosłych – Historie Dzieci [Adult Wars – Children’s Stories]: her husband’s Michał Rusinek’s Zaklęcie na „w” [The “W” Spell] (2011), Dorota Combrzyńska-Nogala’s Bezsenność Jutki [Jutka’s Insomnia] (2012), Irena Landau’s Ostatnie piętro [The Last Floor] (2015), Andrzej Marek Grabowski’s Wojna na Pięknym Brzegu [War on the Beautiful Shore] (2016) and Rafał Witek’s Chłopiec z Lampedusy [A Boy from Lampedusa] (2016). Along with Michał Pawłowski, she runs an independent graphic design studio Kreska i Kropka [Stripe’n’Dot Studio].

Sources:

Cymer, Anna, Joanna Rusinek, 2013, available here (accessed: February 22, 2018).

Bio prepared by Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Adaptations

In 2017, a group of animators from Łódź Drama Academy carried out a project inspired by, inter alia, Bezsenność Jutki. It consisted of various workshops, in which teachers and students from Łódź took part. One of the results of the project was a spectacle based on Combrzyńska-Nogala book, directed by Hanna Jastrzębska-Gzella and played by children and adults representing several Łódź schools.

Preparations to produce an animated movie based on Bezsenność Jutki are under way. An application for funding the project was submitted by Tessa Moult-Milewska (EGo Film) for consideration by the Polish Film Institute’s ‘Film Production’ operational programme 1/2018.

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

The book is set in Łódź during WW2. A small Jewish girl Jutka Cwancygier lives in the Łódź [Litzmannstadt] Ghetto with her grandfather Dawid and her aunt Estera. The girl doesn’t understand the gravity of the situation. She tries to spend her time playing with friends or her tame rook named Wawelski and listening to her grandfather’s stories (on many subjects, such as Polish folklore or Greek mythology). On the other hand, she also learns how to survive under these terrible conditions. One day, Jutka and her family move to a house near the wall of the Ghetto. She finds a friend in Basia, a little girl from behind the walls. They talk often and Basia even enters the Ghetto to give Jutka apples and let her play with a kitten. When the operation ‘Wielka Szpera’ [Aktion Gehsperre – "Great Search"]* begins, Jutka hides in the basement and waits for her family. When the "Szpera" ends, it is revealed that Jutka’s grandfather bribed some people and obtained "Aryan" documents for the girl and her aunt. Both leave the Ghetto together (it is unclear what happened to them later and what happened to Jutka’s grandfather but as far as we know he remained in Łódź). It is suggested that Basia’s mother helped the women escape: she probably exchanged messages with Jutka’s grandfather using the girl’s tame rook.

* The word “Szpera” derives from German “Allgemeine Gehsperre” meaning a general curfew, a ban on leaving homes. The Aktion Gehsperre started on September 5, 1942 and ended a week later. Houses in the Ghetto were searched by Jewish policemen and German gendarmes in order to find all the elderly, ill and infirm people and children under 10 years old. More than 15 000 people were sent to an extermination camp in Chełmno upon Ner [Kulmhof]. In addition, many people were killed because they refused to part with their families. Very few children under 10 (those who managed to hide and the children of Jewish superior officers and policemen who took part in the Aktion Gehsperre) survived these events, according to: Joanna Podolska, Łódź żydowska. Spacerownik [Jewish Łódź: A Walking Guide], Łódź: Agora S.A., 2009, 124–125.

Analysis

In children’s and young adult literature, the Holocaust is often presented with the use of the fantastic – for example, Jane Yolen in Briar Rose (1992) and Joanna Rudniańska in XY (2012) utilized certain fairy-tale motifs and conventions. However, Dorota Combrzyńska-Nogala’s Bezsenność Jutki proposes another way of telling a story about the horrible times: by referencing classical antiquity. In this book, Jutka’s grandfather tells her stories deriving from Greek mythology: the story of the Minotaur, Theseus and Ariadne, and of Icarus and Daedalus. The girl interrupts him comparing these myths with the reality of the war: for instance, for Jutka the Labyrinth of Crete resembles a prison, Icarus could have been shot down by a German officer and the hero’s mother who wasn’t mentioned in the myth could have been taken to the Ghetto. After listening to these stories, Jutka also compares German gendarmes to the Minotaur – in the illustration by Joanna Rusinek, we see one of the Nazis, but only as a shadow trying to chase children, therefore the gendarme is portrayed as a kind of an evil force*. When the "Szpera" begins, Jutka is scared, but her grandfather tells her that Theseus survived in the Labyrinth in the dark. He also, in order to give courage to the girl, gives her a ball of wool.

The stories about mythological heroes and heroines, told to Jutka by her grandfather – “the metaphorical Ariadne” (Rybak, 2016), help the girl to face the horror reality of the Holocaust, the time of the Aktion Gehsperre in particular. Donald Haase’s words, although the scholar refers to fairy tales, seem to be relevant in the case of Combrzyńska-Nogala’s book too, as here: […] we see the liberating potential of the imagination at work […]. Whether, in these extreme circumstances, the genre’s appeal and the imaginative work it generates amount to denial depends ultimately on the value we give to hope**. In Bezsenność Jutki, the limit of hope is also reliant on the reader’s interpretation of the story. As Katarzyna Marciniak states: The women leave the Ghetto. The Grandpa stays and probably dies. The girl probably survives the war. The world is not black-and-white and Combrzyńska-Nogala makes her young readers aware of this. And nothing serves such aim better than ancient myths (Marciniak, 2015, 82).

However, the author also builds, as it was indicated earlier, the image of the Nazis as resembling the Minotaur. It could be interpreted as a way of fairy-tale-like portraying them as extremely terrifying and evil***. This accordance to the bipolar axiology can be seen as helping both Jutka and the audience to somehow ‘settle in’ the broken, unintelligible world****. The choice of the figure of the Minotaur strongly corresponds to the fact that in Bezsenność Jutki the Ghetto is similar to a labyrinth. As Krzysztof Rybak writes: "It is a closed, crowded, limited territory made of narrow, winding paths. It is also a destiny for many Jews, who will die there (like the Athenian youths) or be transported to Nazi camps later"*****, which is very well presented in the illustrations by Joanna Rusinek.

* Rusinek explained that: “[…] making illustrations to this book was a hard and painful task;” what is more, “in the graphics that were created, kept in grey and black tones, the author tried to present the little heroine’s close ones’ warmth and kindness rather than show tragedy”. After: Anna Cymer, Joanna Rusinek, 2013, available at www.culture.pl (accessed: July 12, 2018).

** Donald Haase, “Children, War, and the Imaginative Space of Fairy Tales”, The Lion and the Unicorn 24.3 (2000): 360–377, 373.

*** One of the Nazis later in the book spares Jutka, showing mercy; Katarzyna Marciniak considers that the scene: “[…] proves that the author avoids stereotypes and simplifications in presenting Germans”. After: Katarzyna Marciniak, “(De)constructing Arcadia: Polish Struggles with History and Differing Colours of Childhood in the Mirror of Classical Mythology”, in Lisa Maurice, ed., The Reception of Ancient Greece and Rome in Children’s Literature: Heroes and Eagles, Leiden: Brill, 2015, 56–84.

**** It is interesting that the Nazis are often shown as or compared to creatures both in children’s and young adult literature and in popular culture, to mention Ransom Riggs’s novel Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children (2011), Marcin Szczygielski’s book Arka czasu [Rafe and the Ark of Time] (2013), or Tommy Wirkola’s zombie film Død snø [Dead Snow] (2009).

***** Krzysztof Rybak, Childhood in the Labyrinth of the Ghetto: Nazis as Minotaurs in Children’s Literature about Shoah, 2016, available at academia.edu (accessed: July 12, 2018).

Further Reading

Adelson, Alan and Robert Lapides, eds., Łódź Ghetto: Inside a Community under Siege, New York: Penguin Books, 1991.

Haase, Donald, “Children, War, and the Imaginative Space of Fairy Tales”, The Lion and the Unicorn 24.3 (2000): 360–377.

Howorus-Czajka, Magdalena. “‘True Fiction’ – the Memory and the Postmemory of Traumatic War Events in a Picturebook”, Problemy Wczesnej Edukacji / Issues in Early Education 3.34 (2016): 94–106, available online at pwe.ug.edu.pl (accessed: July 12, 2018).

Marciniak, Katarzyna, “(De)constructing Arcadia: Polish Struggles with History and Differing Colours of Childhood in the Mirror of Classical Mythology”, in Lisa Maurice, ed., The Reception of Ancient Greece and Rome in Children’s Literature: Heroes and Eagles, Leiden: Brill, 2015, 56–84.

Podolska, Joanna, Łódź żydowska. Spacerownik [Jewish Łódź: A Walking Guide], Łódź: Agora S.A., 2009.

Rybak, Krzysztof, Childhood in the Labyrinth of the Ghetto: Nazis as Minotaurs in Children’s Literature about Shoah, 2016, available at academia.edu (accessed: July 12, 2018).

Rybak, Krzysztof, “Hide and Seek with Nazis: Playing with Child Identity in Polish Children's Literature about the Shoah”, Libri & Liberi 6.1 (2017): 11–24, available online at librietliberi.org (accessed: July 22, 2018).

Skibińska, Ewa, Bezsenność Jutki, available online at ryms.pl (accessed: July 12, 2018).

Skowera, Maciej, “Polacy i Żydzi, dzieci i dorośli. Kto jest kim w Kotce Brygidy Joanny Rudniańskiej i Bezsenności Jutki Doroty Combrzyńskiej-Nogali” [Poles and Jews, Children and Adults: Who is who in Kotka Brygidy by Joanna Rudniańska and Bezsenność Jutki by Dorota Combrzyńska-Nogala], Konteksty Kultury 11.1 (2014): 57–72, available online at ejournals.eu (accessed: July 12, 2018).

Wójcik-Dudek, Małgorzata, W(y)czytać Zagładę. Praktyki postpamięci w polskiej literaturze XXI wieku dla dzieci i młodzieży [To Read into the Holocaust: Post-Memory Practices in the 21st Century Polish Literature for Children and Adolescents], Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, 2016.

Addenda

Bezsenność Jutki was published under the patronage of the Polish Commissioner for Children’s Rights in "Literatura" publishing house’s series Wojny Dorosłych – Historie Dzieci [Adult Wars – Children’s Stories] in 2012, which marked the 70th anniversary of the "Szpera."

The illustration (pp. 32–33) showing Jutka and her grandfather with a ball of wool (a reference to the story of Theseus and Ariadne), courtesy of the publisher.

The illustration (pp. 50–51) presents Jutka and her friends trying to escape from the monster-like Nazi, courtesy of the publisher.