Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

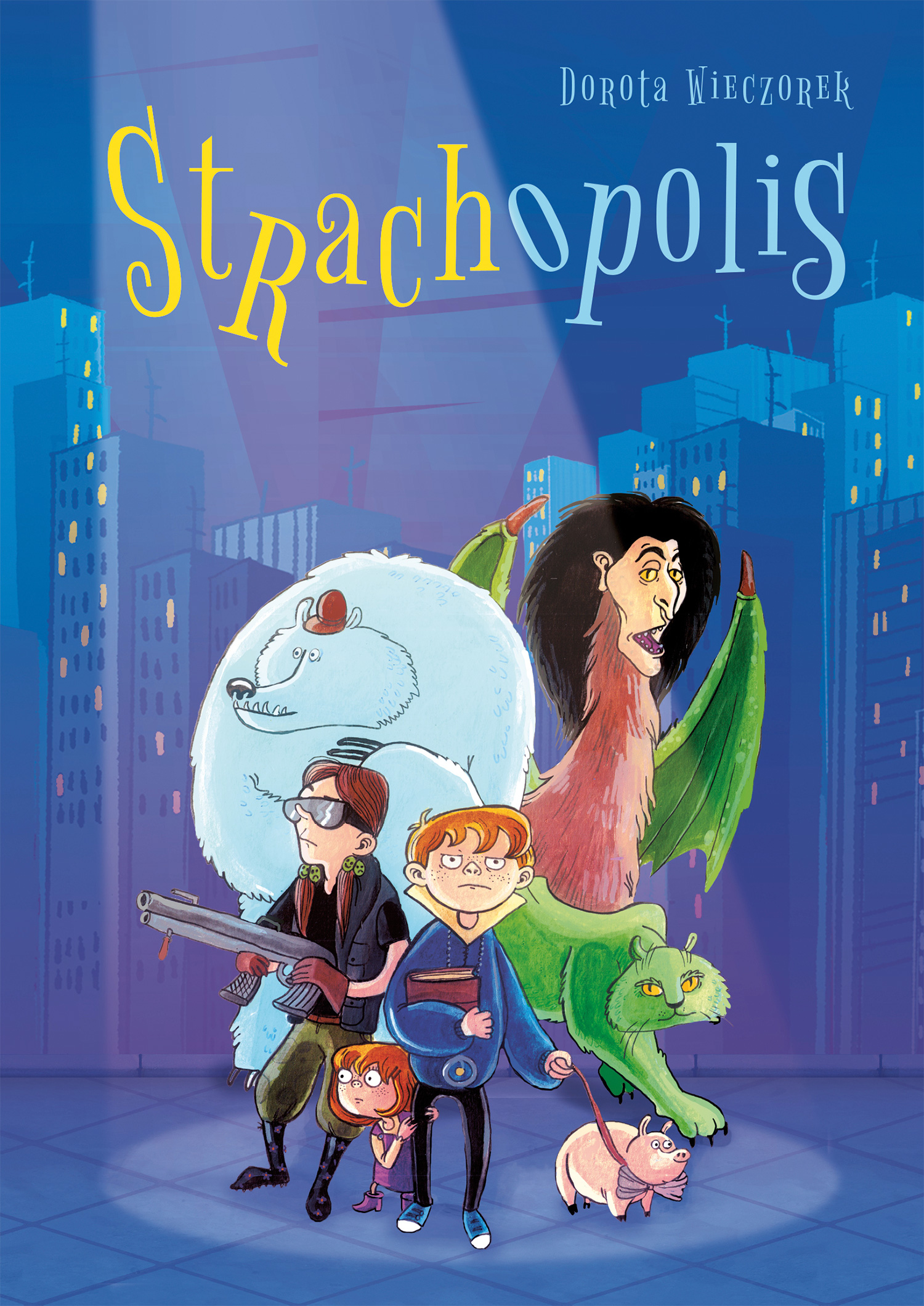

Wieczorek Dorota, ill. Nikola Kucharska, Strachopolis. Warszawa: Skrzat, 2015, 320 pp.

ISBN

Awards

2015 – mention in the “Book of the Year” contest, organised by the Polish Section of IBBY.

Genre

Bildungsromans (Coming-of-age fiction)

Fantasy fiction

Illustrated works

Novels

Target Audience

Children (according to the publisher’s website: 10+)

Cover

Cover courtesy of Skrzat.

Author of the Entry:

Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Courtesy of the Illustrator.

Nikola Kucharska

, b. 1993

(Author)

Nikola Kucharska was born on November 2, 1993 in Chorzów, Poland. She is a graphic designer, illustrator and author of comic books, and illustrator of board games. She holds a B.A., from the Academy of Fine Arts in Katowice. She has illustrated many children’s books, such as Dorota Wieczorek’s Strachopolis [Monsteropolis] (2015) and Katarzyna Wasilkowska Królestwo jakich wiele [A Kingdom Like Many Others] (2016), and also authored her own books, including Podróż dookoła świata. Północ – południe, wschód – zachód [A Journey Around the World: North – South, East – West] (2016), nominated for “The Most Beautiful Book of the Year” award by the Polish Association of Book Publishers, Kobo w supermarkecie [Kobo in a Supermarket] (2017), co-created with Michał Kubas, and Jak to działa? Zwierzęta [How Does It Work? Animals] (2017). Among her works, there are also wimmelbooks retelling well-known stories: Legendy polskie dla dzieci w obrazkach [Polish Legends for Children in Pictures] (2016) and Greek Myths for Children in Pictures [Mity greckie dla dzieci w obrazkach] (2017). Her works have been translated into several languages and published, inter alia, in France, China, Russia, and Czechia. On her website, she describes herself as a reader of everything, from shampoo labels to classical literature. She collects rubber bands, birds’ feathers and antiques. As a hobby, she writes short stories on an old typewriter. She also admits on her website to owning three black cats and one brownish grey (see here, accessed: June 28, 2018).

Bio prepared by Hanna Zarzycka, University of Warsaw, hanna.zarzycka@student.uw.edu.pl and Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Courtesy of the Author.

Dorota Wieczorek

, b. 1982

(Author)

A Gdynia-born writer, graphic designer, copywriter. She graduated in Polish Philology from the University of Gdańsk and completed postgraduate studies in book illustration at the Władysław Strzemiński Academy of Art in Łódź. She has published several children’s and young adults’ fantasy and science fiction novels: Dotyk mroku [The Touch of Darkness] (2011), Statek magów [The Wizards’ Ship] (2012), Strachopolis [Monsteropolis] (2015), and Jesień magii [The Autumn of Magic] (2016). She has also authored works in the field of didactics of teaching and actively takes part in the actions performed by the Odyssey of the Mind Poland, a section of an international educational programme aiming to develop creative thinking of children and young adults. As a member of the foundation, she coached the competing teams for seven years and, now, is a referee. She is a fan of Fantasy and Science Fiction. When asked about the books she would bring to a desert island, she mentioned works by Anne McCaffrey, Orson Scott Card, Frank Herbert, Kir Bulychov, and Peter S. Beagle. She also likes René Goscinny’s and Jean-Jacques Sempé’s books about Little Nicolas.

Sources:

An interview with Dorota Wieczorek conducted by Darek Baczewski, 2011, available at www.literatura.gildia.pl (accessed: October 1, 2018).

Additional information kindly provided by the Author.

Bio prepared by Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Summary

The title city is a place in which people live together with all kinds of monsters. While many of them have been integrated into society, the others have to hide away refusing to comply with existing conditions. The protagonist of the novel, Kostek and his sister, Niezapominajka [Forget-Me-Not], grow up among these creatures. The siblings, as it turns out, are the long-lost children of Baltazar Brylski, one of the most famous so-called “fearslayers” – usually superhero-like monster hunters. Kostek and Niezapominajka, found in the monster-inhabited city sewers by the “antimonsterists,” are informed about their father’s sudden death. The children move to their family residence, where they live with their aunts, Grozilla [Fearzilla] and Relania (the name derived from the word “Relanium,” which is a medicine based on diazepam). The next part of the book tells about Kostek’s attempts to find his father’s killer – a creature called “strachulec” (this name combines Polish “strach,” which means “fear,” and “gargulec” – “gargoyle”). The boy, accompanied by his father’s assistant, Przerażający Igor [Igor the Scary], and a female fearslayer, called R.I.P., becomes involved not only in a quest for revenge, but also in the social crisis in Strachopolis. The crisis is the result of inappropriate attitudes towards monsters, based on their exploitation, marginalization, and forced integration into the human-dominated society. Eventually Kostek, with the help of his human and monster friends, defeats his father’s murderer – a shapeshifting creature pretending to be the mayor of Strachopolis. At the end of the novel, we read about progressive changes in the city, including granting civic rights to all monsters.

Analysis

The book deals with a motif which is now highly-relevant to children’s literature and culture: the figure of a monster, who has its roots, inter alia, in classical antiquity, including the myths “inhabited” by various non-human creatures. According to Katarzyna Slany, in Wieczorek’s text, supernatural beings constitute “a cultural construction and a sign to be read,” the aim of which is to make potential young readers aware of “the semblance of the meaning that arose around the figure of monster,”* and also to highlight metaphorically the problematic consequences of marginalizing minorities.

Wieczorek’s novel can be seen as a reworking of Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book (1894) as well as of the myth of the origin of Rome. Here, however, the lost children are raised not by animals, but by monsters – which makes Strachopolis similar to other works where the motif of supernatural guardians is used, The Graveyard Book (2008) by Neil Gaiman and Miasteczko Ostatnich Westchnień [The Town of Last Sighs] (2014) by Grzegorz Gortat. The protectors of Kostek and Niezapominajka are not only largely popular creatures, such as a vampire and a zombie, but also mutated or mutilated animals: a green panther and a one-legged bear. This menagerie is led by Chimeron – a character based on the Greek mythological creature usually depicted as being composed of the parts of a lion, a goat, and a snake. We read that: “[...] he was a Chimera, a monster born of other monsters. His face was almost human, covered with scarcely visible wildcat-like spots, but had torso and legs of a lion, a dragon tail, bat wings, and a dark tangled mane of… unknown origin.”** Slany writes that the author of the novel refers to the “the icon of the grotesque,” but presents this being as a “humanized phantom,” as Kostek’s friend who has “great intuition, knowledge, and a sense of responsibility for the community of free monsters.”*** In one of the most dramatic episodes of the book, Chimeron sacrifices himself to save his protegee (however, it turns out that he did not die), which makes him a Messiah-like figure.****

In the book, we also read about the Sewage Seer. Kostek and his friends, on Chimeron’s suggestion, seek this character looking for a way to defeat the antagonist. As it turns out, the Sewage Seer is not a typical oracle, but an old, obese, seemingly unfriendly man, who welcomes the disoriented group with the following words: “What did you expect? […] A tulle skirt and a magic wand? My name is Smord. […] I’m a sewer worker. […] I’m the best at this job and, sometimes, I deal with magic. From time to time, humans and monsters come here and ask me to foretell their future, so I pretend that I do it. Occasionally, my prophecies are correct, so? Well… I’m lucky.”***** Slany, referring to the quoted fragment, writes that the Sewage Seer is a caricature of the Delphic Pythia, and that this parody “relies on grotesque decontextualization of the mythical pattern, which in effect, leads the reader to dialogical interaction resulting from the novel’s irreverent convention.” However, as the protagonist learns, this man occasionally manages to see the future correctly in his crystal ball, and he helps the group by leading them to the heart of the city – a secret place, hidden underground and covered in light, which, to Kostek’s amazement, allows him to overpower the killer of his father.

* Katarzyna Slany, “Czy w Strachopolis Doroty Wieczorek straszy?” [Is Dorota Wieczorek’s Strachopolis Haunted?], Creatio Fantastica 1(56) (2017): 7–23, p. 14.

** Dorota Wieczorek, Strachopolis, Warszawa: Skrzat, 2015, 38–39, all quotations translated by Maciej Skowera.

*** Slany, 2017, 18.

**** See: Slany, 2017, 18.

***** Wieczorek, 2015, 258–259.

Further Reading

Gryzipiór, Księga miejskiej dżungli, czyli Strachopolis Doroty Wieczorek [The Book of Urban Jungle, or Strachopolis by Dorota Wieczorek], available online at www.gryzipior.pl (accessed: September 24, 2018).

Slany, Katarzyna, “Czy w Strachopolis Doroty Wieczorek straszy?”, Creatio Fantastica 1(56) (2017): 7–23.

Addenda

The illustration (p. 39) showing Kostek with Chimeron, courtesy of Skrzat.

The illustration (p. 258) showing the Sewage Seer, courtesy of Skrzat.