Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

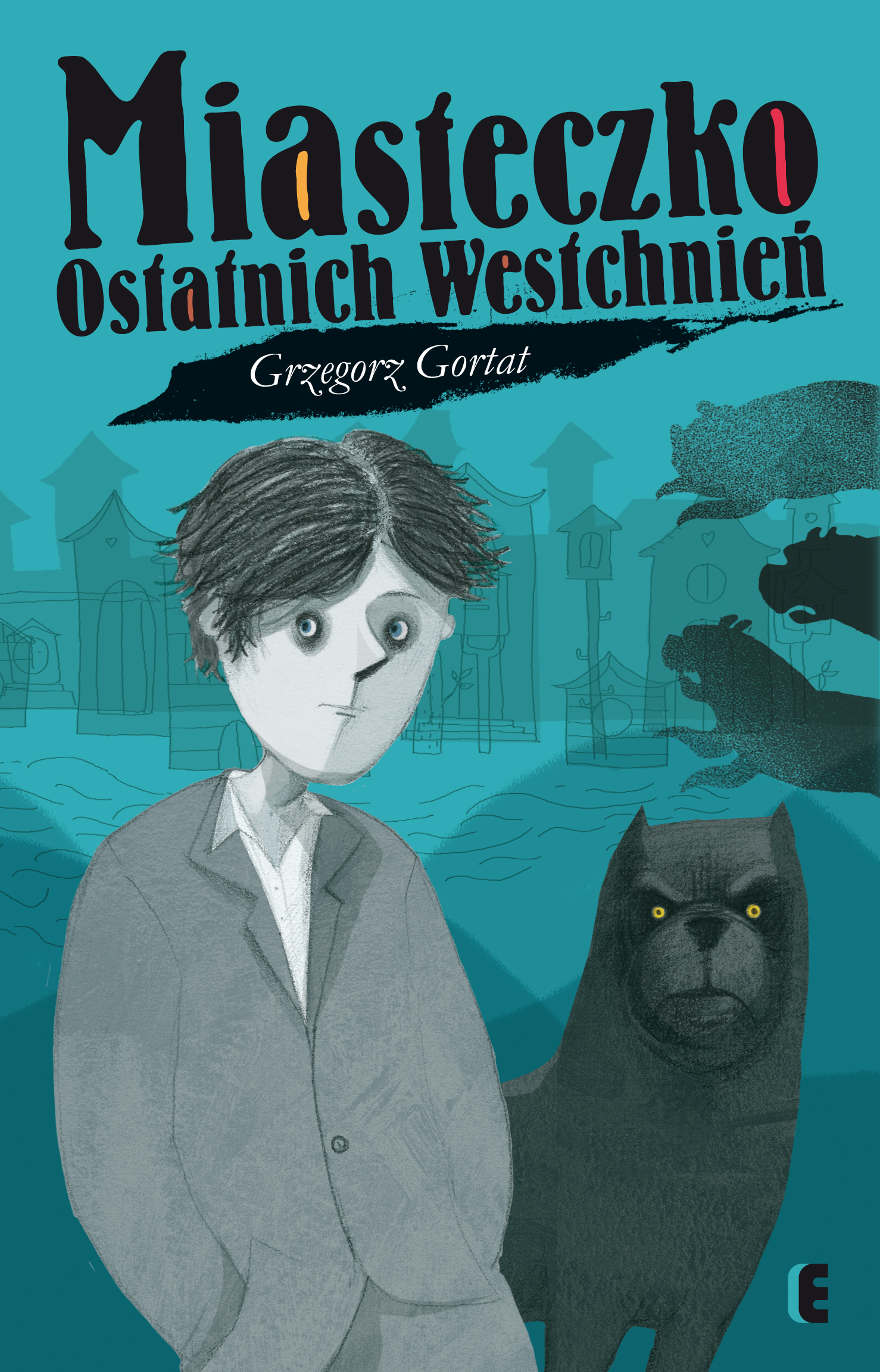

Grzegorz Gortat, ill. Marta Krzywicka, Miasteczko Ostatnich Westchnień. Warszawa: Agencja Wydawnicza Ezop, 2014, 170 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Bildungsromans (Coming-of-age fiction)

Fantasy fiction

Fiction

Illustrated works

Novels

Target Audience

Crossover (According to the publisher’s website: 12+)

Cover

Courtesy of Agencja Edytorska EZOP.

Author of the Entry:

Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Courtesy of the Author.

Grzegorz Gortat

, b. 1957

(Author)

A writer, translator of English literature, a former teacher. He graduated in English Philology from the University of Warsaw and is a well-known and critically acclaimed author of children’s literature. His works in this field include: Świt Kambriddów [The Dawn of the Kambridds] (2000), Cień Kwapry [The Shadow of Kvapra] (2002), Muszkatowie, czyli jeden za wszystkich, wszyscy za jednego [The Mushkatov Kids: All for One, One for All] (2013), Ewelina i Czarny Ptak [Ewelina and the Black Bird] (2013), Nie budź mnie jeszcze [Don’t Wake Me Up Just Yet] (2013), Miasteczko Ostatnich Westchnień [The Town of Last Sighs] (2014), Piętnaście kroków [Fifteen Steps] (2015), and Moje cudowne dzieciństwo w Aleppo [My Wonderful Childhood in Aleppo] (2017). He also writes books for adults and young adults, such as Do pierwszej krwi [Till First Blood] (2008), Zła krew [Wrong Blood] (2009), Szczury i wilki [Rats and Wolves] (2009), or Mur [The Wall] (2017). In his works, Gortat uses various genres (horror fiction, fantasy novel, crime story) and discusses such problems as death, loneliness, racism, the Holocaust, and war. He received the main award in the 9th “Polish Association of Book Publishers’ Literary Contest” and three honorary mentions in the IBBY Poland’s “Book of the Year” contest. In April, 2018, Moje cudowne dzieciństwo w Aleppo was awarded a “Special Phoenix” by the Association of Catholic Publishers.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: October 1, 2018)

Gortat, Grzegorz. “O mnie/ About me,” available online at grzegorzgortat.pl (accessed: October 1, 2018).

Profile at the nk.com.pl (accessed: October 1, 2018).

Additional pieces of information kindly provided by the Author.

Bio prepared by Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Questionnaire

1. Why do you think classical / ancient myths, history, and literature continue to resonate with young audiences?

I believe there is a substantial area of topics that kids living two thousand years ago might share with their peers of the 21st century. The world of heroes, twists of fortune, supernatural elements is something that would equally fascinate both audiences so distant historically. Another thing kids of today and their ancient predecessors would have in common is that they would rather associate themselves with Hercules than Icarus. Which leads us to an observation that young Nero or Seneca might find it relatively easy to accept the world of Superman as his own.

2. Do you have a background in classical education (Latin or Greek at school or classes at the University?) What sources are you using? Scholarly work? Wikipedia? Are there any books that made an impact on you in this respect?

As a senior high school student I was expected to memorize Latin words and grammar as part of my Latin language education. “Memorizing” came easier than “understanding,” but some Latin legacy did stay with me till this day. And so did my fascination for the ancient world. For reference, I mostly use my collection of books which includes both academic texts and works of classical authors as well as popular fiction.

3. Did you think about how Classical Antiquity would translate for young readers, esp. in Poland?

GG: Frankly, I don’t have an immediate answer. One way of trying to make young readers take interest in ancient topics would be to tie them to popular literature and movies. As for my personal experience, the trick that works in most cases is to put teenagers of today in the shoes of their ancient peers. There is no better way to get acquainted with the daily realities of life centuries ago than through walking the narrow alleys of Rome and buying a lunch from a street vendor. Well, young man, don’t expect the menu will include hamburgers and French fries.

4. Why is the protagonist of your novel named “Grakch”? Is it an allusion to the Gracchi brothers, Tiberius and Gaius?

Actually, Grakch is a modified version of the name of the protagonist of Franz Kafka’s story The Hunter Gracchus. I am a big fan of Kafka and I love to smuggle elements of his fiction into my novels for adults and young readers alike. But I borrowed the name from Kafka not just to hint my admiration to Franz. When you think about it, there is some remarkable resemblance between Gracchus the Hunter, who, dead to the mortals, drifts in a boat down the river between the world of the dead and the world of the living, and Grakch the Boy, who crosses the river that separates the afterlife world of animals from the land of humans.*

5. The rats in your novel are named “Romulus” and “Remus.” Why did you decide to reverse the situation known from the myth of the founding of Rome, in which Romulus and Remus were human children raised by an unnamed she-wolf?

Reversing myths is something most authors really like. You take a myth like a fabric and cut it to finally tailor the pieces to the needs of the narrative. One important consideration is to surprise the readers and make them really focused – not an easy challenge in the social-media era when according to experts young recipients of content can digest only small portions of information. Now, confronting the readers as early as on the opening page with Romulus and Remus the Rats might bring an element of surprise that prompts them to go to the next page. Besides, the readers feel invited to an open-end game in which the Rats are tasked with raising the human baby. Sounds familiar but different at the same time?

6. Not only the rats, but also all the other animals living in the Town can choose new names after they die. As the idea of naming is supposed to be a human one, does it make them still dependent on the mankind? Or maybe you see it, conversely, as a sign of the animals’ independence and freedom?

In the haven they go after death (which is the last stop before they proceed to their version of Paradise), the animals are free to take their own decisions for the first time ever. In their earthly life, they were given names, if at all, by people. Now, as an expression of free will, they can assume a name they want. This is an act of regaining self-respect and freedom they were deprived of in their previous existence.

Prepared by Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

*Note that Franz Kafka’s work mentioned by Grzegorz Gortat is sometimes discussed in the context of the brothers Gracchi. See, for example, Peter Fenves, “‘Workforce without Possessions’: Kafka, ‘Social Justice,’ and the Word Religion, in Freedom and Confinement in Modernity: Kafka’s Cages, A. Kiarina Kordela, Dimitris Vardoulakis, eds. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, 107–126.

Courtesy of the illustrator.

Marta Krzywicka

, b. 1975

(Illustrator)

A graphic designer and illustrator. She graduated from the Faculty of Graphic Arts at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw and completed postgraduate studies in publishing policy and bookselling at the University of Warsaw. She creates illustrations for children’s and adult books and designs books, including textbooks, from their layouts to covers. She has worked for various Polish publishing houses and illustrated many books for the younger audience, to mention Iwo z Nudolandii [Iwo from Boringland] (2017) by Dorota Suwalska, Koniki z szumińskich łąk [The Horses from Szumin Meadows] (2014–2016) by Agnieszka Tyszka, and Grzegorz Gortat’s novels published in “Ezop” publishing house’s series Lepiej w to uwierz! [You better believe it!].

Sources:

Official website (accessed: October 1, 2018)

Bio based on information kindly provided by the author.

Bio prepared by Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Summary

The Town of Last Sighs is a place where animals called “Domestics” – for example dogs, goats and pigs, but also a circus elephant – go to when they die, and where they stay until they decide to leave and enter the Land of Eternal Rewards. Unexpectedly, two rats, Romulus and Remus, find a living male infant in a garbage bag near the River separating the Town from the empirical world. The inhabitants of the Town do not know what to do with this “human puppy.” Only Raben, a dog, is sure that they should get rid of the “intruder.” Eventually, the “Domestics,” joined by one of the “Free” – a she-wolf called Mori – decide to try the case at their court to determine the infant’s fate. During the court case, they bring back memories about how they were harmed by humans when they were alive. Nevertheless, all the animals except Raben think that the child should be spared and stay with them. However, the verdict must be unanimous – this is why the baby is condemned to death. The dog, appointed executioner, cannot stand the boy’s crying and, therefore, does not kill him.

A few years pass. The boy is loved and protected by the animals – however, Raben does not seem to be very friendly towards him. One day, the human becomes aware that he is different from his guardians, as they tell him: “You’re not a bird! […] Nor a goat […]. Don’t wonder you’re an elephant […] or a pig. […] And you don’t resemble a horse at all. […] Look at your reflection in the water. Are you similar to any of us? No, you’re not. Because you’re not one of us. […] You were born human and it cannot be changed.”* The boy thinks about the world behind the River more and more. Eventually, Raben and the child visit the wise White Tiger who confirms the dog in his conviction that his companion belongs to the human world. It is also revealed that the boy’s name is Grakch, which was written on the note found years before by the rats.

Although humans cannot become animals, the opposite is possible: the animals can go back to the domain of life as humans, but they must return to the Town before the third sunrise. Raben decides to undergo such a metamorphosis to help Grakch. They cross the River and enter the city of Riministanza, where an election of a mayor is going to take place. One of the candidates turns out to be Vincent Teuffel – who happens to be both Grakch’s biological father and Raben’s former cruel owner.

He is an evil man who trains dogs for fights and kills the “weaker” ones, as he is obsessed with the ideas of “perfection” and “purity.” This also applies to his own family: his first son was born with one leg shorter, so Teuffel placed him in an orphanage (where the boy died), and “got rid” of his mother, probably by killing her. The man’s second wife gave birth to twins. One of them is Grakch, born with a gland on his back, and therefore rejected by his father who ordered him to be killed (which did not happen). The second twin, Sven, did not have such a “flaw,” so Teuffel kept him – but the protagonist’s brother turned out to be empathic towards animals and attached to his mother. Perceiving all of this as weaknesses, the father imprisons him in the basement and constantly tortures him. When the father realizes that Grakch is alive, he locks him up and tortures him too. Grakch, Sven and Raben, with the aid of Mrs. Laura Teuffel, the boys’ mother released from the asylum, defeat the father. The family is reunited, while Raben, still in a human form (he did not return to the Town on time) plans to visit Litzmannburgh, a city where he was born and died as a dog.

* Grzegorz Gortat, Miasteczko Ostatnich Westchnień, ill. Marta Krzywicka, Warszawa: Agencja Wydawnicza Ezop, 2014, 35–36. Quotation translated by Maciej Skowera.

Analysis

In a similar way to The Graveyard Book (2008) by Neil Gaiman and Strachopolis [Monsteropolis] (2015) by Dorota Wieczorek, Gortat’s novel reworks Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book (1894). However, the story of Mowgli is not the first narrative which uses the motif of the child brought up by animals.

According to the myth of the founding of Rome, Rhea Silvia, a Vestal Virgin and a descendant of Aeneas, gave birth to twins, Romulus and Remus, whose father was Mars. Rhea Silvia’s uncle, Amulius who previously overthrew her father Numitor to take the throne of Alba Longa, imprisoned the woman and ordered the children to be drowned in the River Tiber. His servants spared the boys who were found by a she-wolf. They lived with the animal until Faustulus, a shepard, discovered them. When Romulus and Remus grew up, they defeated their uncle and restored Numitor’s rule. Then, the young adults begun founding their own city, which was later called Rome.*

In The Town of Last Sighs, the situation is quite similar: animals find an abandoned child, one of the twins, who was ordered to be killed by being drowned in the river, while the mother was being imprisoned. However, in this case, the she-wolf is Mori, who does not raise the baby, and it is two rats who are named Romulus and Remus. This reversal of the mythological way of naming is interesting, as here, the animals get names – it is worth mentioning that they choose their new names after they die and to not use the ones given by humans anymore. The rats’ names, taken from the myth, can be seen as a symbol of their individuality, subjectivity, and independence – also when we keep in mind that a she-wolf who raised Romulus and Remus was unnamed. In effect, the novel can be interpreted as going further than the myth itself in presenting animals as important “actors” of the story. Not only do they perform actions, but are also individualized by naming themselves, which contrasts with Grakch’s own situation, as he does not know his real name for the first years of his life.**

* See: Michael Newton, Savage Girls and Wild Boys: A History of Feral Children, London: Faber & Faber, 2011, pp. 18–19. However, according to some variants of the myth, the city was founded on blood, as Romulus killed his brother Remus.

** Although Grzegorz Gortat himself does not think of this issue this way (see the Author’s Questionnaire), from the perspective of some branches of animal studies, and of posthuman thought in general, this can be also interpreted as an anthropocentric act of dependence – the Town animals, including rats, use the human names as if they were not able to abandon the roles of subaltern beings.

Further Reading

Jacques, Zoe, Children’s Literature and the Posthuman: Animal, Environment, Cyborg, New York: Routledge, 2015.

Newton, Michael, Savage Girls and Wild Boys: A History of Feral Children, London: Faber & Faber, 2011.

Rąbkowska, Ewelina, “Pozaedukacyjny zwierzyniec? Przekształcenia motywu raju zwierząt w polskiej literaturze fantastycznej dla dzieci i młodzieży” [Extra-Educational Bestiary? Transformation of Animal Paradise Motif in Polish Young Adult Fantastic Literature], Creatio Fantastica 2(53) (2016): 83–95.

Skowera, Maciej, “Literackie spotkania istot podporządkowanych. Studium przypadku: Miasteczko Ostatnich Westchnień Grzegorza Gortata” [Literary Encounters of Subaltern Beings. Case Study: Grzegorz Gortat’s The Town of Last Sighs], in Czytanie menażerii. Zwierzęta w literaturze dziecięcej, młodzieżowej i fantastycznej [Reading a Menagerie: Animals in Children’s Young Adult, and Fantasy Literature], Anna Mik, Patrycja Pokora, and Maciej Skowera, eds., Warszawa: Wydawnictwo SBP, 2016, 53–74.

Addenda

Miasteczko Ostatnich Westchnień was published in “Ezop” publishing house’s series Lepiej w to uwierz! [You better believe it!], which consists of children’s horror, gothic, and supernatural novels. The other books by Gortat published in this series are: Ewelina i Czarny Ptak (2013), Nie budź mnie jeszcze (2013), and Piętnaście kroków (2015).

“Ezop,” the name of the publishing house, is the Polish equivalent of “Aesop.”

The illustration (p. 13) showing Grakch as an infant, accompanied by the Town animals, including the rats: Romulus and Remus, courtesy of Agencja Wydawnicza Ezop.

Copyrights

[Cover] Courtesy of Agencja Wydawnicza Ezop.

[Illustration] Courtesy of Agencja Wydawnicza Ezop.

[Gortat’s portrait] Courtesy of the Author.

[Krzywicka’s portrait] Courtesy of the Author.